Macaronesia (7,821 – 6,094 BCE): Early Holocene …

Years: 7821BCE - 6094BCE

Macaronesia (7,821 – 6,094 BCE): Early Holocene — Cloud-Forest Realms and Arid Shields at Sea’s Edge

Geographic & Environmental Context

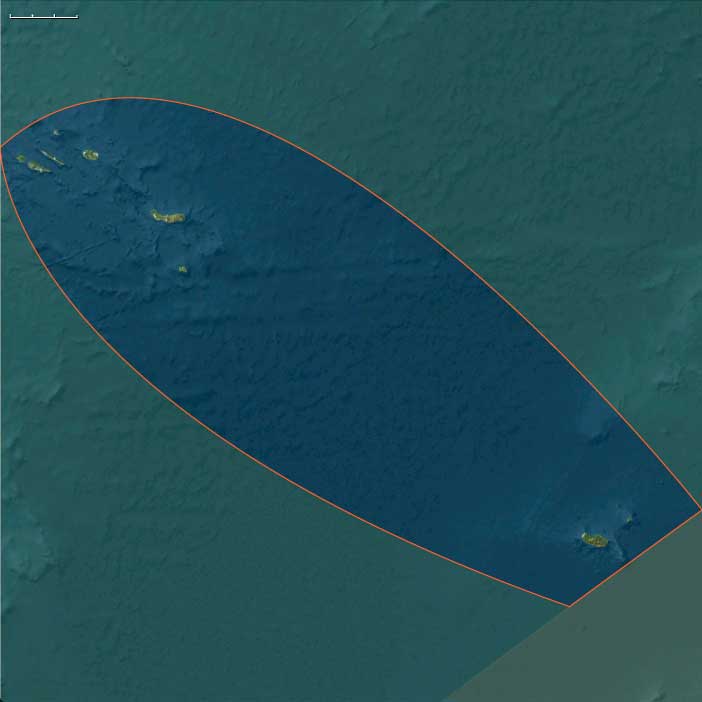

In the Early Holocene, Macaronesia—the mid-Atlantic archipelagos of the Azores, Madeira–Selvagens, Canaries, and Cape Verde—stood as a chain of isolated volcanic worlds, each molded by orography, ocean currents, and the unbroken rhythm of trade winds.

-

Northern Macaronesia—the Azores and Madeira–Selvagens—lay in the humid temperate belt, where fog-fed laurel forests and crater-lake wetlands flourished.

-

Southern Macaronesia—the Canary and Cape Verde Islands—spanned a steep gradient from the lush cloud-forest summits of Tenerife and La Palma to the arid, wind-swept shields of Lanzarote, Fuerteventura, Sal, and Boa Vista.

All remained uninhabited, connected only by ocean currents and the aerial networks of seabirds and spores.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

The Holocene thermal optimum ushered in warm, humid stability across the North Atlantic subtropics:

-

Persistent trade winds maintained orographic rainfall on windward slopes, nurturing cloud forests on high islands.

-

Leeward zones remained drier, forming semi-desert scrublands on low volcanic plains.

-

The Canary Current carried cool upwellings along the African margin, moderating temperatures and enriching marine productivity.

-

Seasonal fog interception built self-sustaining hydrological cycles, with montane forests acting as atmospheric condensers.

This climatic equilibrium yielded maximum vegetative extent and peak biodiversity across the archipelagos.

Subsistence & Settlement

No humans yet visited Macaronesia; its ecosystems evolved autonomously:

-

Northern islands (Azores, Madeira, Selvagens): dense laurisilva forests of laurel, heather, and juniper dominated uplands; crater lakes and marshes hosted invertebrate-rich wetlands; seabird colonies carpeted cliffs, fertilizing soils with guano.

-

Southern islands (Canaries, Cape Verde): strong vertical zonation developed—humid evergreen forests at mid-elevations; pine–juniper belts higher; arid steppe vegetation in lowlands. On Fogo, Santo Antão, and Santiago, fog-fed highlands contrasted sharply with desert flats on Sal and Boa Vista.

-

Coastal and islet zones teemed with penguins, petrels, shearwaters, and seals; intertidal flats supported rich mollusk beds.

Guano-driven fertility and isolation produced a living experiment in island biogeography, still untouched by human influence.

Technology & Material Culture

None. While continental neighbors advanced polished-stone and ceramic technologies, Macaronesia remained wholly pre-anthropic, its only “tools” the wind, waves, and the biological machinery of colonization.

Movement & Interaction Corridors

Macaronesia was linked not by human voyages but by ecological and atmospheric exchange:

-

The Canary Current and North Atlantic Gyre circulated nutrients, driftwood, and spores.

-

Seabirds and windborne seeds bridged hundreds of kilometers between island groups, maintaining genetic flow.

-

Occasional storm-driven drift from Iberia or northwest Africa may have delivered organic material—or, conceivably, the first accidental vertebrate migrants—but sustained human navigation was millennia away.

Cultural & Symbolic Expressions

No human symbolic systems existed, yet the archipelagos themselves embodied natural metaphors of balance and contrast: the humid forests of the north against the sun-bleached shields of the south; fog as life-giver, drought as sculptor. Each island stood as an ecological shrine of self-contained renewal.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

Macaronesian ecosystems perfected island resilience through ecological feedback:

-

Cloud interception and fog drip recycled atmospheric moisture into groundwater.

-

Guano enrichment and volcanic soils sustained diverse endemic floras.

-

Altitudinal zonation buffered against climate shifts: if drought struck lowlands, montane cloud belts still condensed moisture.

-

Arid-island endemics evolved succulence and deep roots, while montane species adapted to humidity and wind.

These mechanisms ensured long-term ecological stability in complete isolation.

Long-Term Significance

By 6,094 BCE, Macaronesia had reached its Holocene ecological zenith:

-

Northern Macaronesia stood draped in cloud forests, crater-lake wetlands, and seabird rookeries of astonishing density.

-

Southern Macaronesia balanced lush volcanic summits against austere coastal deserts, each sustained by fog and seabird fertility.

-

Across all islands, life was vigorous yet untroubled, its complexity born solely of ocean, wind, and stone.

These islands—laurisilva sanctuaries in the north, volcanic fortresses in the south—would remain pristine for thousands of years more, silent witnesses to the unfolding drama of Holocene climate and the eventual spread of humankind.