Macaronesia (6,093–4,366 BCE): Middle Holocene — Cloud …

Years: 6093BCE - 4366BCE

Macaronesia (6,093–4,366 BCE): Middle Holocene — Cloud Forests, Currents, and the Unseen Isles

Geographic & Environmental Context

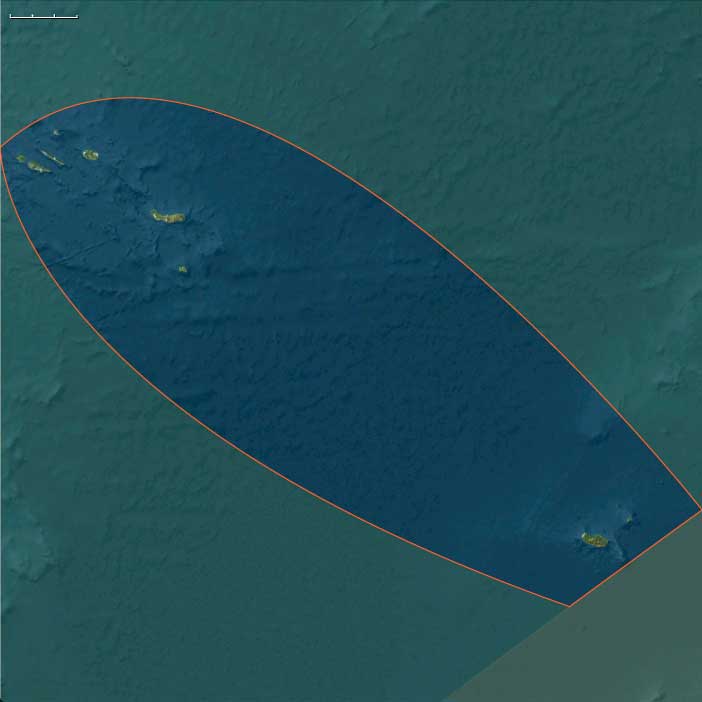

Macaronesia—the scattered volcanic archipelagos of the Azores, Madeira, Selvagens, Canary Islands, and Cape Verde—formed a constellation of mid-Atlantic ecosystems poised between Africa, Europe, and the open ocean.

In the Middle Holocene, these islands were entirely uninhabited, their only histories written by wind, wave, and life itself.

-

The northern chains—Azores and Madeira–Selvagens—lay within the temperate influence of the North Atlantic westerlies, sustaining humid laurel forests, crater-lake wetlands, and seabird-dense coasts.

-

The southern groups—Canaries and Cape Verde—flanked the subtropical Canary Current, their climates split between moist, cloud-fed uplands (Tenerife, La Palma) and arid, trade-wind deserts (Lanzarote, Fuerteventura, Sal, Boa Vista).

Together, they were biological satellites of the African and European mainlands—stepping stones in the ocean’s gyre, each hosting a unique laboratory of evolution.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

The Hypsithermal optimum (7000–4000 BCE) brought warm, stable conditions and rising seas that stabilized coastlines near modern form.

-

The African Humid Period was fading: the Sahara and Sahel began to dry, but Canarian uplands still captured orographic mist.

-

Cape Verde, farther west and drier, entered a period of intensifying aridity, its slopes clothed in thorny scrub and drought-tolerant grasses.

-

Northern Macaronesia remained perpetually humid, wrapped in cloud belts and steady drizzle, feeding laurel forests (laurisilva) and moss-draped ravines.

Oceanographically, the Canary Current and North Atlantic Gyre maintained cool upwellings along the African coast, making nearby seas nutrient-rich and biologically explosive.

Subsistence & Settlement

No human presence marked these islands.

Ecological communities operated in self-contained equilibrium:

-

Azores & Madeira: forests of laurel, heather, and juniper blanketed volcanic plateaus and slopes; streams fed crater-lake basins teeming with algae and aquatic invertebrates.

-

Canary Islands: cloud-fed highlands nurtured dragon trees, pines, and laurels, while coasts hosted palm groves and saline scrub.

-

Cape Verde: sparse vegetation—grasses, succulents, and drought-hardy shrubs—held thin soils against erosion.

-

Across all islands, seabirds and turtles nested in vast numbers; marine mammals and pelagic fish (tuna, dolphins, whales) frequented surrounding waters.

The islands functioned as nurseries for birds, seals, and reptiles, and as rest stations for long-range migrants.

Technology & Material Culture

In this era, Neolithic societies elsewhere around the Mediterranean and North Africa mastered farming, pottery, and seafaring, but none yet crossed the Atlantic margin to Macaronesia.

The only “technologies” shaping these islands were volcanism, erosion, and the ecological machinery of colonization—wind-blown seeds, ocean-drift wood, and nutrient cycling through guano and detritus.

Movement & Interaction Corridors

Though unpeopled, Macaronesia was woven into the wider Atlantic system:

-

The Canary Current and North Equatorial Countercurrent carried marine nutrients, drifting seeds, and pumice between Africa, Europe, and the Americas.

-

Migratory seabirds stitched the archipelagos together, moving nutrients and genetic material from pole to tropic.

-

Whale migrations and turtle routes paralleled these gyres, making the region one of the biological crossroads of the Atlantic millennia before human ships arrived.

These dynamic exchanges ensured that even in isolation, Macaronesia was never disconnected from the world ocean.

Cultural & Symbolic Expressions

No human culture inscribed meanings here, but the islands themselves embodied natural symbolism:

-

Cloud forests mirrored the sky’s cycles, turning mist into rain and life.

-

Turtle crawls and seabird rookeries recurred with clockwork precision, marking the seasons like ritual.

-

Volcanic renewal and forest succession created living archives of fire and rebirth—the planet’s own mythos of creation and renewal written in stone and green.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

Island ecosystems demonstrated remarkable adaptive specialization:

-

Laurisilva canopies trapped moisture from passing clouds, maintaining internal hydrologies.

-

Drought-adapted shrubs and succulents dominated Cape Verde’s arid flanks, maximizing scarce rainfall.

-

Seabird colonies and turtle populations redistributed nutrients from sea to land, fertilizing soils and anchoring ecological continuity.

Disturbance—volcanic ash, storm surge, or landslide—was followed by rapid recolonization, reinforcing long-term ecological resilience.

Long-Term Significance

By 4,366 BCE, Macaronesia stood as a fully mature Atlantic wilderness, untouched by humans yet intricately linked to planetary processes.

-

The northern archipelagos (Azores–Madeira–Selvagens) were lush, cloud-fed sanctuaries of endemic flora.

-

The southern groups (Canaries–Cape Verde) displayed the early divergence between humid and arid biomes, precursors to their modern contrasts.

-

The surrounding Canary Current system supported vast marine productivity, acting as a biological corridor for species that would later sustain seafarers.

Though unseen by human eyes, Macaronesia had already achieved its defining balance: volcanic land reborn through wind and rain, bound to the rhythms of ocean and sky—a natural prelude to the later story of navigation, colonization, and transformation.