Macaronesia (49,293–28,578 BCE): Upper Pleistocene I — …

Years: 49293BCE - 28578BCE

Macaronesia (49,293–28,578 BCE): Upper Pleistocene I — Volcanic Refugia in the Glacial Atlantic

Geographic and Environmental Context

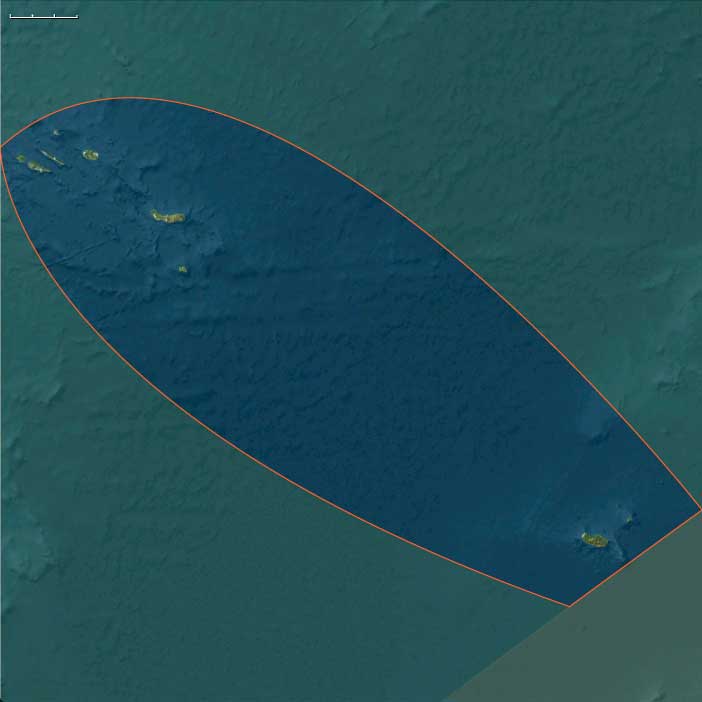

The Macaronesian World of the Upper Pleistocene comprised two major archipelagos—Southern Macaronesia, including the Canary Islands and Cape Verde, and Northern Macaronesia, encompassing the Azores, Madeira, Porto Santo, and the Selvagens.

Both chains rose as isolated volcanic summits from the deep Atlantic basin, positioned between Europe, Africa, and the Americas yet belonging fully to neither. Their steep bathymetric reliefs left only narrow coastal benches, while interior slopes climbed abruptly to mist-wrapped summits.

This structural duality—north humid, south arid—reveals the essence of the region’s identity in The Twelve Worlds: though grouped under one regional name, the Macaronesian archipelagos were ecologically distinct, their climates and biotas responding more to latitude, wind, and current than to one another.

Southern Macaronesia: Canary–Cape Verde Realm

-

Setting: The Canaries, lying nearest Africa, and Cape Verde, farther into the Atlantic, were both volcanic shield systems surrounded by the Canary Current and constant northeast trades.

-

Topography: High islands such as Tenerife and Gran Canaria carried deep ravines and high calderas; La Palma and El Hierro bore active faults; Fuerteventura–Lanzarote and eastern Cape Verde (Sal–Boa Vista) remained low, arid, and wind-swept.

-

Climate: During glacial times, cooler seas and a strengthened trade-wind inversion created marked aridity at low elevations but maintained fog-fed laurel forests on high, windward slopes.

-

Biota: Cloud-forest trees—Laurus azorica, Ocotea foetens—thrived above arid belts of euphorbia scrub. Seabird colonies blanketed offshore stacks; endemic reptiles, geckos, and flightless rails evolved in isolation.

-

No humans were present. Life followed the rhythms of wind, fog, and surf, unshaped by fire or clearing.

Northern Macaronesia: Azorean–Madeiran Realm

-

Setting: North of 30° N, the Azores and Madeira–Selvagens chains experienced stronger Atlantic westerlies and frequent cyclonic rains.

-

Topography: Volcanic cones, crater lakes, and laurisilva-clad ridges alternated with sheer cliffs and talus plains.

-

Climate: Though global conditions were colder, humidity remained high; fog forests persisted even through glacial droughts.

-

Biota: Dense evergreen woodland (juniper, laurel, heather) supported unique birds—giant pigeons, owls, and rails—and enormous seabird rookeries on the Selvagens.

-

Isolation: With no continental shelves, the islands stood aloof from both Europe and Africa, their species radiations paralleling, not mirroring, those of the Canaries or Cape Verde.

Climate and Environmental Dynamics

At the Last Glacial Maximum, global sea level dropped ~100 m, briefly widening each island’s coastal rim but leaving the overall geography unchanged.

-

Northern islands remained humid refugia, mild under the westerlies.

-

Southern islands oscillated between fog-forest caps and desertic lowlands as trade-wind intensity varied.

Storm tracks intensified across the mid-Atlantic, bringing winter surf and episodic rainfall but few extremes beyond those already natural to these oceanic outposts.

Movement and Interaction Corridors

Only air and sea currents linked the archipelagos:

-

The Canary Current and the North Atlantic Drift swept nutrients and seeds westward.

-

Migratory birds shuttled seasonally between Europe, Africa, and these islands, transporting spores and invertebrates.

-

The islands themselves were stepping-stones for life, not for people—biological but not cultural nodes.

Cultural and Symbolic Context

To contemporary humans on the continents, Macaronesia did not exist.

The chains lay far beyond Pleistocene seafaring horizons, unimagined in myth or memory.

Later ages would cast them as Atlantis-like realms or Isles of the Blessed, but in this epoch they were purely natural sanctuaries—laboratories of evolution unobserved by human eyes.

Environmental Adaptation and Resilience

-

Flora: Adapted to poor soils, high winds, and fog-drip moisture; many species evolved reduced dispersal and gigantism typical of island “syndromes.”

-

Fauna: Flightless birds and reptile endemics balanced fragile yet self-sustaining food webs; seabird guano enriched thin volcanic soils.

-

Ecosystem resilience: Cycles of eruption, erosion, and recolonization fostered remarkable ecological stability despite global climatic swings.

Transition Toward the Glacial Maximum

By 28,578 BCE, the twin worlds of Macaronesia stood pristine:

-

The northern high islands blanketed in cloud forests, buffered from glacial cold by Atlantic humidity.

-

The southern shields—Canaries and Cape Verde—divided between lush fog-caps and sun-blasted coasts.

No human hand had yet touched them, yet their isolation and biotic richness made them crucial Atlantic refugia.

In the logic of The Twelve Worlds, Macaronesia demonstrates how even within one “region,” distinct subrealms evolve—each more ecologically allied to far-off worlds than to its neighboring chain—foreshadowing the layered complexity of the Holocene globe to come.