Macaronesia (28,577 – 7,822 BCE): Upper Pleistocene …

Years: 28577BCE - 7822BCE

Macaronesia (28,577 – 7,822 BCE): Upper Pleistocene II → Early Holocene — Deglaciation, Forest Recovery, and Untouched Islands

Geographic & Environmental Context

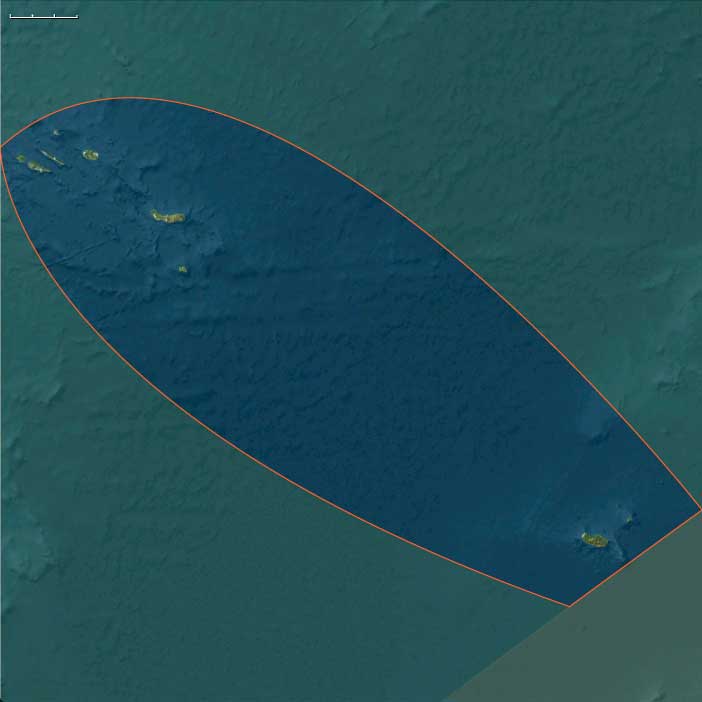

Macaronesia—the North Atlantic’s chain of volcanic archipelagos scattered off northwestern Africa—was transformed during the long transition from the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM) to the Early Holocene.

The region comprised two major clusters:

-

Southern Macaronesia: the Canary Islands (Gran Canaria, Tenerife, La Palma, La Gomera, El Hierro, Fuerteventura, Lanzarote) and the Cape Verde group (Sotavento and Barlavento chains).

Here, rugged volcanic highlands (Teide, Taburiente, Fogo) contrasted sharply with low, arid shield islands such as Lanzarote and Sal–Boa Vista. -

Northern Macaronesia: the Azores, Madeira, Porto Santo, and the Selvagens Islands—younger oceanic volcanoes rising from the mid-Atlantic Ridge, with fertile slopes, crater lakes, and mist-fed forests.

During deglaciation, global sea levels rose 60–80 meters, submerging coastal benches and reshaping the islands’ outlines. New calas, coves, and cliffs formed as landslides and eruptions reworked shorelines—especially in the Canaries and Azores. Yet throughout this entire epoch, no humans had arrived. The islands’ history remained entirely ecological.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

-

Last Glacial Maximum (c. 26,500–19,000 BCE):

Cooler and drier conditions contracted forests. In the Canaries and Madeira, montane belts shrank and lowland scrub dominated; Cape Verde became semi-arid and wind-scoured. -

Bølling–Allerød (c. 14,700–12,900 BCE):

Warming and increased humidity expanded laurisilva cloud forests on higher islands (Madeira, La Gomera, Tenerife) and pine–juniper woodlands on mid-altitudes; fog interception strengthened hydrology. -

Younger Dryas (c. 12,900–11,700 BCE):

A short cool, dry interval reduced montane forest area and stressed endemic flora; dune and steppe scrub advanced on lower islands. -

Early Holocene (post-11,700 BCE):

Stable warmth and strong Atlantic trades reestablished humid cloud belts; laurisilva and evergreen canopies recovered fully on Madeira, La Gomera, and Tenerife, while drought-adapted shrublands persisted on Fuerteventura, Lanzarote, and Cape Verde.

The result was a mosaic of microclimates—humid, lush peaks rising above arid lowlands—a balance that would persist into the Holocene.

Flora, Fauna, and Ecological Development

Without humans, Macaronesia evolved as an untouched ecological laboratory:

-

Flora:

• On high islands (Tenerife, Madeira, La Gomera, São Miguel): evergreen laurel forests (laurisilva) expanded, fed by fog-drip hydrology.

• Mid-elevation zones carried pine and juniper woodlands; lowlands bore thermophilous scrub, palms, and succulents.

• In Cape Verde, aridity favored acacias, euphorbs, and grasses, with isolated groves on fog-catching slopes. -

Fauna:

• Rich endemic birdlife (pigeons, finches, shearwaters), reptiles, and insects filled niches left open by the absence of mammals.

• Seabird colonies—shearwaters, petrels, and terns—nested on cliffs and islets, their guano enriching soils and driving nutrient cycles.

• Offshore waters teemed with tuna, dolphins, and sea turtles, reflecting nutrient input from upwelling and island-mass effects.

Environmental Processes and Dynamics

-

Volcanism & Erosion: Intermittent eruptions (notably on Tenerife, La Palma, Fogo) renewed soils, adding mineral fertility.

-

Sea-Level Rise: Drowned coastal terraces became wave-cut platforms, expanding marine habitats.

-

Atmospheric Circulation: Persistent trade winds and temperature inversions maintained distinct cloud belts, feeding perennial fog precipitation that sustained montane vegetation even during dry seasons.

-

Guano Feedback: Massive seabird colonies transported marine nutrients inland, sustaining forest fertility—an early model of biological recycling between sea and land.

Movement & Interaction Corridors

No human crossings occurred, but the archipelagos were ecologically interconnected by:

-

Migratory birds moving between Africa, Europe, and the mid-Atlantic.

-

Wind and current drift of seeds, pumice, and driftwood along the Canary and North Equatorial currents, occasionally linking the islands biologically to distant continents.

-

Volcanic rafting events and storm surges that redistributed soil and biota among the islands.

Cultural & Symbolic Dimensions

There was no human symbolic life here yet.

For the people of Europe and Africa, these islands lay beyond all navigational and mythic horizons—a literal “outside world” unknown to imagination. Their only “stories” were ecological: the cycles of seabird breeding, fog condensation, and forest regrowth—the silent patterns of natural continuity.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

Macaronesian ecosystems displayed remarkable self-regulation and resilience:

-

Fog harvesting by evergreen canopies stabilized water budgets on high islands.

-

Successional renewal followed eruptions and slides, re-seeding disturbed ground.

-

Guano enrichment and volcanic ash maintained soil fertility.

-

Species specialization produced highly endemic floras adapted to steep ecological gradients.

Even during the Younger Dryas setback, microclimate diversity buffered these island ecologies against collapse.

Transition Toward the Holocene

By 7,822 BCE, Macaronesia had settled into a mature Holocene equilibrium:

-

Canary and Madeira laurel forests flourished once more.

-

Cape Verde’s arid landscapes supported drought-tolerant scrub and grass mosaics.

-

Azores volcanic slopes greened under high rainfall and expanding crater-lake wetlands.

-

Selvagens and low islands remained rocky sanctuaries for seabirds.

Still untouched by humans, the archipelagos stood as self-contained worlds, each with complete, functioning ecosystems—humid forests, arid scrubs, and marine oases—that would later astonish the first sailors to encounter them millennia hence.