Macaronesia (2637 – 910 BCE): The Islands …

Years: 2637BCE - 910BCE

Macaronesia (2637 – 910 BCE): The Islands of the Western Wind — Contact and Isolation at the Ocean’s Edge

Regional Overview

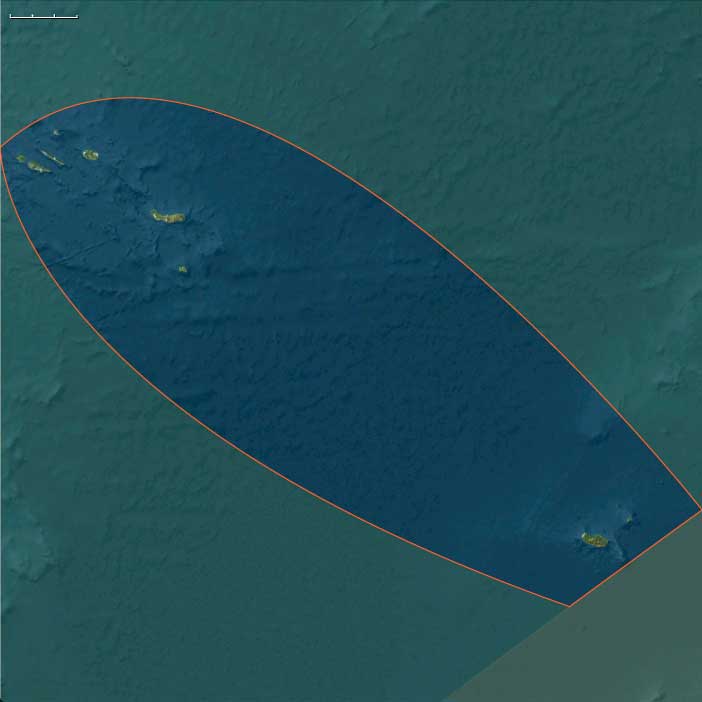

In Early Antiquity, Macaronesia stood at the outermost limit of the known Atlantic.

Its two island groups—the Southern Canaries and Cape Verde near Africa’s shores, and the Northern archipelagos of Madeira and the Azores far out to sea—formed a bridge between continents that no one yet fully crossed.

While the northern islands remained wild sanctuaries of forest and seabird, the southern chain became the westernmost horizon of Amazigh exploration, where small groups of voyagers from North Africa brought their language, herding traditions, and spiritual landscapes into a new island world.

Southern Macaronesia: Guanche–Amazigh Voyaging to the Canaries; Cape Verde Still Empty

The Canary Islands, rising from the Canary Current off northwest Africa, became the first Macaronesian archipelago to host enduring human communities.

By the first millennium BCE, Amazigh (Berber) colonists from North Africa—probably from the western Sahara or coastal Morocco—had reached several of the larger islands: Gran Canaria, Tenerife, La Palma, La Gomera, and eventually El Hierro.

Settlement on the more arid eastern islands (Fuerteventura and Lanzarote) required austere adaptation but succeeded through herding and dry-farming ingenuity.

Subsistence & Lifeways

Islanders practiced barley and pulse cultivation on terraced slopes and in valley bottoms, combined with goat and sheep pastoralism.

They gathered wild figs and coastal shellfish, stored grain in caves and stone silos, and built stone huts or cave dwellings along reliable springs.

Springs and fog-drip were sacred lifelines; their guardianship intertwined with ancestor rites and communal feasts.

Material & Symbolic Culture

With no native metals, the Guanche–Amazigh toolkits remained stone, bone, and fiber-based: polished adzes, grinding stones, hide sandals, leather garments, and woven goat-hair textiles.

Ceramics were plain but functional; basketry and cordage showed high refinement.

Cave burials and occasional mummification on Tenerife and Gran Canaria displayed complex mortuary ritual.

Petroglyphs and idoliform carvings marked sacred peaks and springs, embedding kinship and ritual in the island terrain.

Isolation & Adaptation

Once founded, the communities became self-contained archipelagic societies, with little or no contact with the mainland.

Dryland barley, herding mobility, and grain storage buffered drought years; spring sanctuaries and terracing stabilized fragile soils.

Meanwhile, to the southwest, the Cape Verde Islands—though visible from trans-Saharan wind lanes—remained uninhabited, their volcanic ridges untouched and seabird rookeries untroubled.

Northern Macaronesia: Atlantic Outliers Beyond Known Worlds

Farther north, beyond the reach of Amazigh navigation or Mediterranean trade, the Azores, Madeira, Porto Santo, and the Selvagens remained unpeopled sanctuaries of wind, cloud, and forest.

The Azores’ volcanic cones and crater lakes, the laurel forests of Madeira, and the Selvagens’ seabird cliffspersisted in ecological equilibrium.

Rainfall and volcanic renewal maintained lush soils; no grazing or fire yet disturbed the canopy.

If Bronze Age mariners of Phoenicia or Iberia ever glimpsed these islands, they left no mark.

Symbolic Echoes

In later Mediterranean mythology, tales of the Isles of the Blessed or Hesperides may faintly echo these unseen lands—conceptual horizons rather than charted geography.

For now, they existed solely within nature’s cycles: forests, seabirds, and the Atlantic wind.

Environmental Adaptation & Continuity

Across both halves of Macaronesia, isolation defined resilience.

In the south, herding and granary systems stabilized small human populations amid drought and volcanic soils; in the north, pristine ecosystems endured undisturbed.

Orographic rain, fog-drip, and nutrient upwelling sustained life at all altitudes—from laurel forests to guano-enriched headlands—creating natural laboratories of long-term ecological balance.

Transition

By 910 BCE, Macaronesia embodied two contrasting realities:

-

The Canaries, inhabited by self-reliant Guanche–Amazigh communities cultivating grain and memory in volcanic isolation;

-

Cape Verde, Madeira, and the Azores, still untouched wildernesses, blank on the human map.

The region stood as the western edge of the known world, where early voyagers halted and where, for the next two millennia, the Atlantic wind would guard islands suspended between myth and discovery.