Australasia (49,293 – 28,578 BCE): Upper Pleistocene …

Years: 49293BCE - 28578BCE

Australasia (49,293 – 28,578 BCE): Upper Pleistocene I — Continental Shelves, Fire Country, and the Unpeopled Islands of the Far South

Geographic & Environmental Context

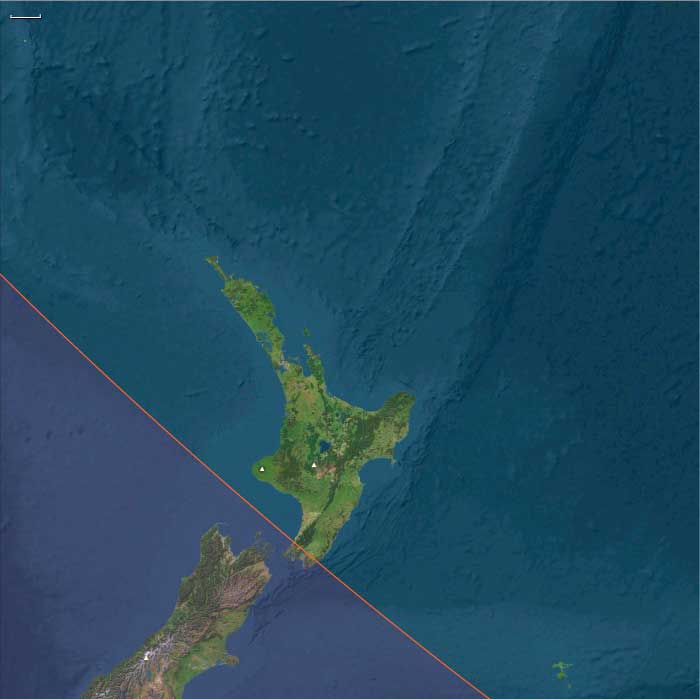

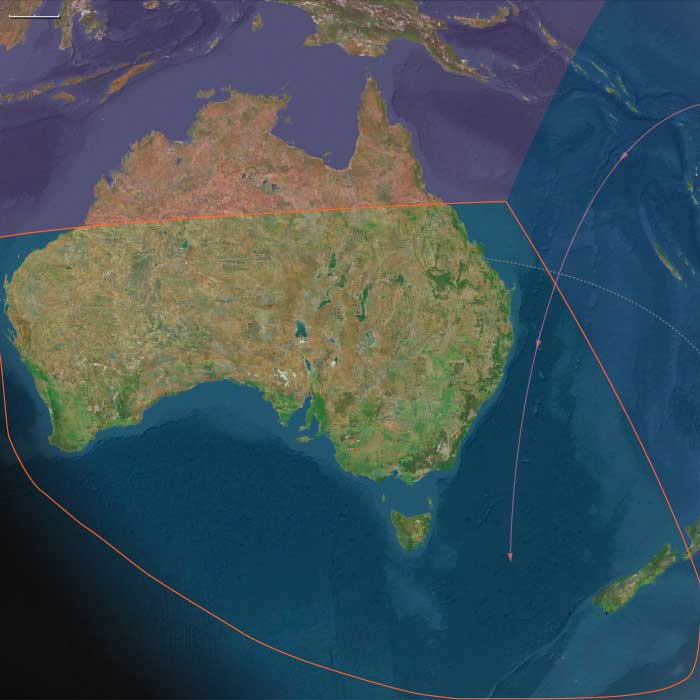

During the long glacial prime of the Late Pleistocene, Australasia stretched as a single vast, connected super-land: the Sahul continent, where Australia, New Guinea, and Tasmania were joined by the broad Arafura and Carpentaria shelves, while across the Tasman Sea, the New Zealand–Norfolk–Kermadec arc stood isolated, volcanically active, and entirely uninhabited by humans.

The region’s physiography displayed extremes of exposure and contrast:

-

To the north, tropical savannas and monsoon coasts extended from Kimberley and Arnhem Land through Cape York to the low divide of southern New Guinea, while the Gulf of Carpentaria held a vast inland sea–wetland complex.

-

Across central and southern Australia, vast dune fields, salt lakes, and desert basins alternated with fertile riverine corridors like the Murray–Darling and the Willandra Lakes.

-

In the south, the Bassian Plain connected the mainland to Tasmania, while New Zealand remained beyond human reach—its forests, volcanic zones, and seabird cliffs untouched.

Sea level lay ~100 m below present, enlarging the continental shelves and exposing wide coastal plains, which were colonized by both humans (in Australia) and dense faunal populations.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

-

Early Glacial Phase (~49–35 ka): Gradual cooling, declining precipitation in continental interiors, and expansion of arid belts; forest contraction in the tropics and southeast.

-

Approach to the Last Glacial Maximum (~35–28 ka): Sharper temperature drop, stronger seasonality, and intensified westerlies and trade winds. Northern monsoons weakened, and interior lakes fell or dried episodically.

-

Regional Contrasts:

• Northern Australia remained humid enough for monsoon-driven wet–dry cycles, sustaining aquatic ecosystems along rivers and coasts.

• Southern Australia and Tasmania cooled markedly, with snowfall on upland ranges and alpine conditions in the Great Dividing Range and Tasmanian highlands.

• New Zealand entered full glaciation: the Southern Alps carried expanded glaciers, and snowlines dropped by hundreds of meters.

The climate oscillated between long cold stasis and short, mild interstadials—conditions that defined both human adaptive strategies and the evolutionary dynamics of uninhabited island ecologies.

Human Presence and Lifeways

Human societies were firmly established across the Australian continent and the connected Sahul landmass, but absent east of the Tasman frontier.

Northern Australasia (Sahul Tropics)

-

Occupation and Range:

Continuous habitation in Arnhem Land, the Kimberley, Cape York, and the Gulf lowlands; movement extended across the Arafura Plain into southern New Guinea. -

Economy:

Broad-spectrum foraging—fish, shellfish, turtles, dugong, and small terrestrial game. During glacial lowstands, coastal groups ranged across the now-submerged shelf flats, exploiting estuaries and reefs. -

Technology:

Sophisticated flake–blade industries, hafted points, resin adhesives, and early ground ochre use; fiber and wooden implements (spears, nets, traps) widely employed. -

Symbolism:

Earliest rock art phases—engraving and pigment painting—appeared in the Kimberley and Arnhem Land, along with structured burials and cremations. -

Resilience:

Estate-based mobility tracked monsoon pulses; access to the flooded Carpentaria lowland and inland freshwater refugia buffered against droughts.

Southern Australasia (Southern Australia, Tasmania, South Island New Zealand)

-

Australia:

Long-settled communities adapted to harsh continental variability. Along the Willandra Lakes and Murray–Darling Basin, people fished, hunted marsupials, collected seeds and tubers, and practiced ceremonial cremation and burial rites (Mungo).

On the expanded southern shelf coasts, foragers harvested shellfish, seals, pinnipeds, and stranded whales, while inland hunters pursued kangaroos, emus, and small marsupials.

The use of fire to manage vegetation—so-called fire-stick farming—maintained open grasslands and supported reliable game. -

Tasmania (then mainland-connected):

Populations ranged across the Bassian Plain, exploiting riverine corridors and coastal flats for waterfowl and fish; early cold-adapted hearth traditions emerged. -

New Zealand and sub-Antarctic arcs:

Entirely uninhabited, though South Island glaciers carved fjords and plains later to support Holocene ecosystems.

Unpeopled Frontiers: South Polynesia and Oceanic Arcs

East of Sahul, the South Polynesian sector (New Zealand, Norfolk, Kermadec, Chatham Islands) remained a wilderness of volcanic highlands, periglacial coasts, and seabird colonies.

The Oruanui eruption (c. 25.5 ka BP) from the Taupō caldera in New Zealand blanketed the North Island and offshore ridges with tephra, reshaping soils, lakes, and drainage systems.

Forests shifted between podocarp–broadleaf canopies and scrub–grassland mosaics; moa and Haast’s eagle dominated terrestrial food webs, while offshore seabird realms thrived on predator-free islets.

Technology & Material Culture

Across Sahul, technology mirrored a mature foraging economy:

-

Stone: flake–blade cores, backed microliths, and grindstones; heat treatment and resin hafting.

-

Organic: spears, clubs, nets, and wooden shields; fiber technology for carrying and trapping.

-

Pigment and ornament: widespread ochre use for painting, body decoration, and burial; shell and tooth ornaments signal social identity.

-

Fire technology: mastery of landscape burning as a central environmental tool.

Movement & Interaction Corridors

-

Land and River Networks: the Murray–Darling, Willandra, and Lake Eyre basins functioned as arteries linking interior and coast.

-

Shelf and Coast Routes: mobile bands traversed the exposed Sahul shelves, harvesting estuarine resources and migrating seasonally.

-

Northern Gateways: travel between northern Australia and southern New Guinea maintained genetic and cultural interchange across the connected shelf.

-

Southern Pathways: the Bassian Plain allowed movement between mainland and Tasmania until postglacial flooding severed the link.

Cultural & Symbolic Expressions

-

Ritual landscapes: rock shelters and burial grounds (e.g., Willandra) reveal early ceremonial organization.

-

Artistic innovation: hand stencils, engraved motifs, and ochre figurative painting predate 30 ka in northern Australia.

-

Fire and mythic space: controlled burning likely embedded in cosmological understanding of land stewardship.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

Australasia’s Pleistocene societies mastered the ecology of variability:

-

Mobility with continuity: shifting among waterholes, estuaries, and resource belts on seasonal rhythms.

-

Storage through knowledge: environmental mapping replaced physical storage—knowing when and where resources renewed was key.

-

Fire as technology: selective burning maintained mosaics that sustained wildlife and plant yields.

-

Refugia strategies: wetlands and monsoon belts offered fallback zones through glacial droughts.

The unpeopled islands to the east, by contrast, evolved ecological self-sufficiency—volcanic fertility, avian abundance, and intact forests awaiting future colonists.

Transition Toward the Next Epoch

By 28,578 BCE, the Australasian world stood poised at the threshold of deglaciation:

-

Sea-level minima connected lands and compressed ecologies into wide continental shelves.

-

Human societies in Sahul had adapted to every climate zone, from arid interior to reef coast, with rich symbolic traditions already in place.

-

Islands beyond the Sahul frontier—New Zealand, Norfolk, Chatham, Kermadec—remained avian kingdoms without humans.

As ice sheets began their slow retreat, the landscapes and coastlines that would shape the Holocene—estuaries, islands, and archipelagos—were already being prepared by the patient interplay of fire, flood, and time.