South Asia (1540–1683 CE) Imperial Roads, …

Years: 1540 - 1683

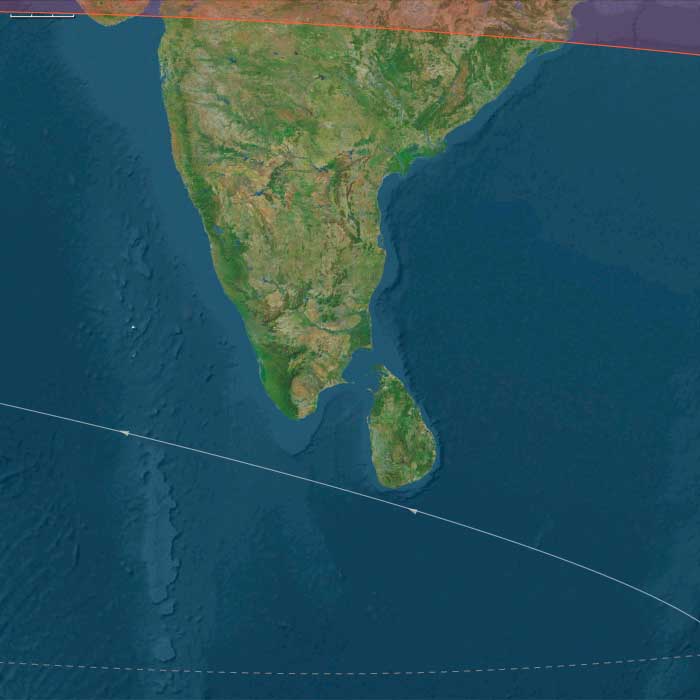

South Asia (1540–1683 CE)

Imperial Roads, Oceanic Crossroads, and the Rise of Early Modern States

Geography & Environmental Context

South Asia in this age encompassed the northern river plains and highlands of Afghanistan, northern India, and Bengal, and the southern plateaus and island worlds of Deccan India, Sri Lanka, and the Maldives—together forming one of the world’s most populous and connected macro-regions. Anchors stretched from the Hindu Kush passes and Indus–Ganges plains to the Krishna–Kaveri river valleys, Ceylon’s cinnamon coasts, and the coral atolls of the Maldives and Chagos. Monsoon-fed agriculture, caravan trade, and maritime routes knit the region into the expanding Afro-Eurasian and global economies.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

The Little Ice Age introduced cooler winters and erratic monsoon patterns. Western disturbances brought snow to the Afghan ranges, while irregular monsoon rains caused alternating floods and droughts across the Gangetic and Deccanplains. Bengal endured recurrent floods and malaria cycles in its wetlands; Sri Lanka’s dry zone saw irrigation decline. The Maldives and Lakshadweep experienced monsoon oscillations and occasional cyclones, but their small-scale economies proved flexible. Despite climatic strain, irrigation and trade ensured regional continuity and resilience.

Subsistence & Settlement

Northern South Asia

-

Indus–Gangetic core: Mixed wheat–barley farming in the northwest and rice–jute–sugar complexes in the east underpinned Mughal prosperity. Sher Shah Suri and later Mughal emperors expanded canals, wells, and tanks, enabling year-round cultivation.

-

Afghanistan and Northwest Uplands: Orchard–grain valleys of Kabul and Peshawar combined with caravan towns along the Grand Trunk Road.

-

Himalayan Rimlands: Nepal and Bhutan sustained terrace agriculture and yak–sheep transhumance, exchanging salt and wool for grain.

-

Bengal Delta: Multi-crop rice cultivation, palm groves, and fisheries supported dense rural populations; cloth weaving thrived along rivers.

-

Arakan and the Chindwin Valley: Maritime Arakanese and Burmese uplanders exchanged rice and slaves with Bengal ports, though by the 17th century Mughal forces pressed westward, curbing Arakanese reach.

Southern South Asia

-

Deccan & Tamil–Telugu regions: After Vijayanagara’s fall (1565), Nayaka and sultanate states sustained tank-irrigated rice, cotton, and indigo production.

-

Malabar Coast: Pepper and spice cultivation flourished under Portuguese monopoly and local patronage.

-

Sri Lanka: The Kandy kingdom controlled uplands and resisted Portuguese encirclement; cinnamon and coconuts drove export wealth.

-

Maldives & Lakshadweep: Island economies rested on coconuts, cowries, and tuna fisheries; Chagos remained uninhabited but entered navigational charts.

Technology & Material Culture

-

Irrigation & infrastructure: Sher Shah’s Grand Trunk Road, sarais (rest houses), and bridges improved trade and defense. Mughals built vast canal networks and reintroduced Persian water-lifting devices.

-

Architecture: Red-sandstone and marble forts, mosques, and gardens—from Delhi to Agra—combined Persian symmetry with Indic motifs. In the south, temple gopurams, bronze icons, and Nayaka murals flourished.

-

Maritime & military technology: Portuguese introduced cannon and ship-mounted artillery to the Indian Ocean; local shipwrights adopted European hull designs while maintaining dhow and teak traditions.

-

Textiles & crafts: Bengal muslins, Gujarat cottons, Coromandel chintzes, and Sri Lankan lacquerware became prized commodities in global markets.

Movement & Interaction Corridors

-

Imperial Roads: The Grand Trunk Road linked Kabul to Sonargaon, moving grain, bullion, and armies across the subcontinent.

-

Caravan Routes: Afghan passes and Himalayan trails connected South Asia with Central Asia and Tibet, exchanging salt, wool, and scriptures.

-

Riverine & Coastal Networks: Bengal’s river system funneled goods to Hugli and Satgaon; Deccan and Malabar ports tied inland markets to the wider Indian Ocean.

-

Oceanic Highways: From Goa and Cochin to Colombo and Aceh, Portuguese and later Dutch VOC fleets monopolized spice routes.

-

European Factories: Portuguese forts (Goa, Diu, Colombo), Dutch trading posts (Pulicat, Galle), and English outposts (Surat, Hugli) integrated the subcontinent into global circuits.

Cultural & Symbolic Expressions

North:

-

Mughal Cosmopolitanism: Akbar’s reign fostered Persianate–Indic synthesis through translation bureaus, miniature painting, and musical innovation. His successors patronized art and monumental architecture—culminating in Shah Jahan’s Taj Mahal.

-

Devotional Movements: Sufi shrines (Ajmer, Pandua) and bhakti saints (Kabir, Chaitanya, Mirabai) transcended religious divides.

-

Sikhism: Founded by Guru Nanak, the Sikh community evolved into a spiritual–martial order under later Gurus, with Amritsar as its sacred and social heart.

South:

-

Temple and Court Culture: Nayaka rulers revived Dravidian temple architecture and patronized Tamil and Telugu literature.

-

Buddhist & Hindu coexistence in Sri Lanka: Kandy’s kings enshrined Buddhist relics even as Portuguese Catholic missions spread along the coasts.

-

Island Islam: The Maldives’ coral-stone mosques and Sufi networks integrated the atolls into the Indian Ocean’s Muslim sphere.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

-

Hydraulic economies: Canals, bunds, and tanks stabilized production in monsoon variability.

-

Crop diversity: Rice–wheat–pulse rotations in the north; rice–cotton–spice cycles in the south buffered shocks.

-

Social safety nets: Waqf and temple estates financed grain storage and famine relief; merchant credit smoothed lean years.

-

Island sustainability: Atoll communities managed coconut, tuna, and coral resources through strict customary law, ensuring long-term resilience.

Technology & Power Shifts (Conflict Dynamics)

-

Sher Shah’s Reforms (1540–1545): Standardized revenue, coinage, and road systems—the durable backbone of Mughal administration.

-

Mughal Ascendancy: Akbar consolidated empire through Rajput alliances and revenue reform; later emperors extended control into Bengal and the Deccan.

-

Deccan and Southern States: After Vijayanagara’s collapse, regional polities and sultanates competed, while Europeans exploited coastal rivalries.

-

European Rivalries: Portuguese dominance waned as Dutch and English companies entered; by the mid-17th century, the VOC controlled Sri Lankan cinnamon and Malacca.

-

Island and Frontier Wars: Acehnese–Portuguese clashes in the west, Mughal–Arakanese contests in the east, and Kandy’s defiance in Sri Lanka reflected regional fragmentation amid global intrusion.

Transition

Between 1540 and 1683, South Asia stood at the heart of an increasingly globalized early modern world.

-

In the north, the Mughals built enduring administrative and cultural systems that unified the subcontinent’s plains and highlands.

-

In the south, the Portuguese and Dutch transformed coastal trade, even as local powers like Kandy and the Nayakas upheld indigenous sovereignty.

-

Across the Indian Ocean, Maldivian sailors, Gujarati merchants, and Bengal weavers sustained networks reaching Arabia, East Africa, and Southeast Asia.

By the close of this era, Mughal grandeur and maritime capitalism had fused two vast worlds—continental and oceanic—laying the groundwork for both imperial consolidation and the colonial incursions that would redefine South Asia in the centuries to come.

People

- Abul Fazl

- Aurangzeb

- Guru Arjan

- Guru Gobind Singh

- Guru Tegh Bahadur

- Humayun

- Jahangir

- Jalaluddin Muhammad Akbar (“the Great”)

- Ngawang Namgyal

- Shah Jahan

- Sher Shah Suri

Groups

- Tajik people

- Kirat people

- Iranian peoples

- Hinduism

- Bengalis

- Pashtun people (Pushtuns, Pakhtuns, or Pathans)

- Jainism

- Kashmir, Kingdom of

- Buddhism

- Buddhism, Tibetan

- Khas peoples

- Indian people

- India, Classical

- Buddhism, Mahayana

- Bon

- Durrani (Pashtun tribal confederacy)

- Islam

- Muslims, Sunni

- Muslims, Shi'a

- Ghilzai (Pashtun tribal confederacy)

- Mongols

- Hazara people

- Malla (Nepal)

- Bengal, Sultanate of

- Gujarat Sultanate

- Sikhs

- Mughal Empire (Agra)

- Mughal Empire (Agra)

- Mughal Empire (Fatehpur Sikri)

- Mughal Empire (Lahore)

- Mughal Empire (Agra)

- East India Company, British (The Company of Merchants of London Trading into the East Indies)

- Dutch East India Company in Indonesia

- Bhutan, Kingdom of

- Portuguese East India Company

- Mughal Empire (Delhi)

Topics

Commodoties

Subjects

- Commerce

- Writing

- Architecture

- Sculpture

- Conflict

- Faith

- Government

- Custom and Law

- Medicine

- Mathematics

- Astronomy

- Philosophy and logic