Southeast Asia (964 – 1107 CE): Angkor’s …

Years: 964 - 1107

Southeast Asia (964 – 1107 CE): Angkor’s Expansion, Pagan’s Rise, Srivijaya at Zenith, and the Maritime Spice Commonwealth

Geographic and Environmental Context

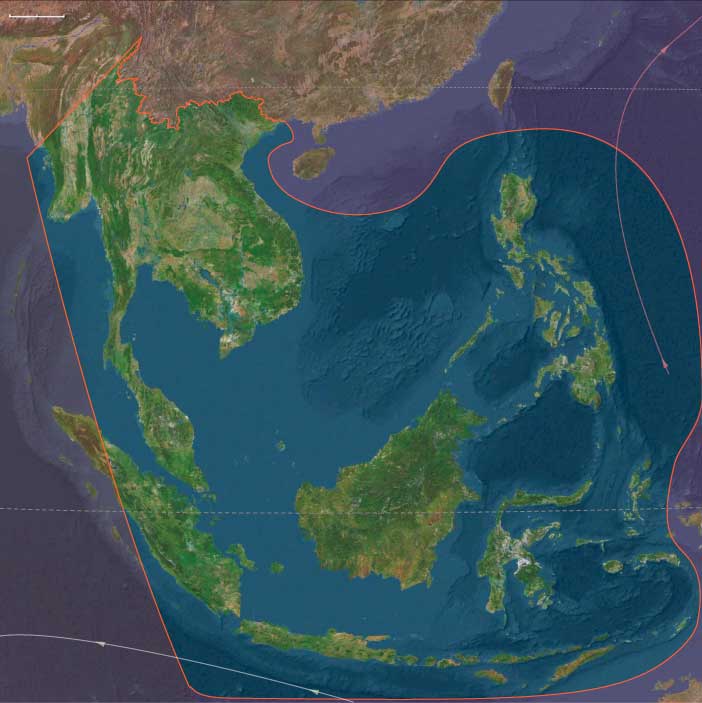

Southeast Asia in the Lower High Medieval Age formed one of the world’s great crossroads—linking the Indian Ocean and the South China Sea through a chain of rivers, deltas, and island straits.

It encompassed the mainland basins of the Irrawaddy, Chao Phraya, Mekong, and Red Rivers, and the insular zones of the Malay Peninsula, Sumatra, Java, Borneo, Sulawesi, and the eastern archipelagos stretching to the Moluccas and Philippines.

Volcanic soils, monsoon-fed lowlands, and reef-fringed coasts sustained a mosaic of agrarian empires and maritime thalassocracies that together forged the most interconnected economy in the tropical world.

Climate and Environmental Shifts

The Medieval Warm Period (c. 950–1250 CE) brought relatively stable monsoon regimes and abundant harvests.

Fertile floodplains enabled the hydraulic expansion of Angkor and Pagan, while volcanic soils in Java and Sumatra yielded surplus rice.

At sea, calmer inter-monsoon intervals favored navigation through the Malacca, Sunda, and Makassar Straits.

Periodic cyclones and El Niño droughts affected coastal polities, but irrigation, redistribution, and maritime trade tempered their impact.

Societies and Political Developments

Across the region, two great systems flourished in tandem—mainland rice kingdoms and insular maritime empires—each adapting Indic and Buddhist influences to local ecologies.

Mainland Southeast Asia

-

Myanmar:

After the Pyu collapse, Burman-speaking groups founded Pagan (Bagan) in the Irrawaddy valley.

Under Anawrahta (1044–1077), Pagan unified Upper Myanmar, institutionalized Theravāda Buddhism, and constructed thousands of stupas and monasteries.

Vast irrigation networks turned dry plains into granaries supporting temple-based patronage. -

Thailand and Laos:

The Dvaravati Mon states declined, absorbed by Pagan and Angkorian expansion.

Lao uplands remained fragmented, while early Thai migrations from the north were laying future foundations. -

Cambodia (Khmer Empire):

Under Suryavarman I (1006–1050), Angkor reached classical scale, extending control into Laos and central Thailand.

Massive baray reservoirs and canals powered rice surpluses, while temples like Phimeanakas embodied a fusion of Hindu and Buddhist royal ideology. -

Vietnam:

The Lý dynasty (1009–1225) centralized power at Thăng Long (Hanoi), balancing Buddhist devotion with Confucian administration.

Southward, Champa thrived along the coast, constructing Mỹ Sơn towers and contesting borders with both Khmer and Dai Viet.

Insular Southeast Asia

-

Srivijaya (Sumatra and the Malay Peninsula):

At its zenith, Palembang’s fleets controlled both the Malacca and Sunda Straits, taxing commerce between India and China.

Srivijaya’s Buddhist monasteries attracted international scholars, sustaining Sumatra’s renown as a center of learning. -

Java:

Divided among rival courts, central Java maintained Shaiva-Hindu temples and rice-based prosperity, while coastal ports sought autonomy from Srivijaya’s maritime dominance. -

Borneo and Sulawesi:

Srivijayan influence reached coastal Borneo; interior Dayak societies continued forest cultivation.

On Sulawesi, coastal chiefdoms in Makassar, Buton, and the north served as brokers of cloves and nutmeg from the Moluccas into the Java Sea network. -

Eastern Archipelagos (Bali – Timor – Moluccas – Philippines):

The Banda and Moluccan Islands exported cloves and nutmeg to world markets through Srivijayan routes.

In the Philippines, barangay polities ruled by datu chiefs expanded bay settlements trading gold, pearls, forest resins, and slaves.

The Sulu and Mindanao zones linked Philippine and Moluccan circuits, while Bali combined rice and root-crop systems with Hindu court culture.

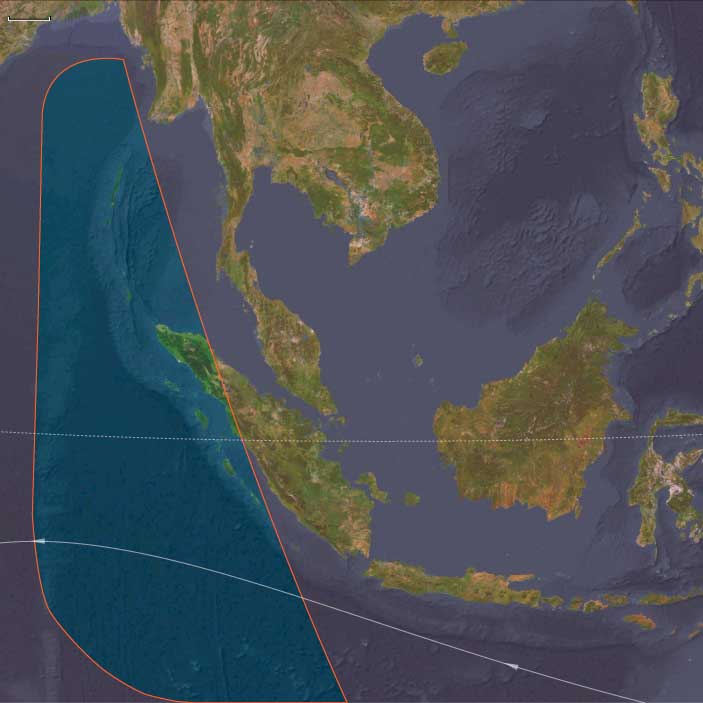

Andamanasia: Northern Gateway of the Bay of Bengal

The Andaman and Nicobar Islands, Aceh, Nias, Mentawai, and nearby archipelagos formed a western threshold of Southeast Asia.

-

The Andamanese preserved autonomous foraging traditions.

-

The Nicobars practiced mixed horticulture and seafaring exchange.

-

Nias and the Mentawais fostered stratified village societies and megalithic feasting cultures.

-

In northern Sumatra, ports such as Barus and Lambri prospered from the camphor trade, attracting Indian, Persian, and Arab merchants.

After the Chola raid of 1025, Srivijaya’s dominance waned, allowing these ports increasing independence and direct access to global commerce.

Economy and Trade

Southeast Asia’s prosperity rested on the fusion of hydraulic agriculture and maritime redistribution.

-

Mainland: Angkor’s and Pagan’s irrigated rice economies sustained monumental architecture and Buddhist institutions; the Lý and Champa realms combined agrarian surplus with coastal trade.

-

Insular: Srivijaya monopolized the spice, gold, and tin routes, linking the Indian Ocean with the South China Sea.

Java and the Philippines supplied rice and forest products, while the Banda–Moluccas produced the coveted clove and nutmeg that fueled world demand. -

Andamanasia: Barus and Lambri exported camphor and elephants, becoming vital nodes in the Indian Ocean economy.

Together, these systems created a maritime commonwealth, moving rice, metals, forest resins, and aromatics across thousands of kilometers of sea.

Belief and Symbolism

Religion unified political authority and artistic expression throughout the region.

-

Angkor: Hindu-Buddhist cosmology materialized in temple-mountain architecture.

-

Pagan: Theravāda Buddhism institutionalized monastic learning and temple endowments.

-

Vietnam (Lý): Buddhism intertwined with Confucian governance.

-

Champa: Shaiva Hinduism merged with Austronesian ritual at Mỹ Sơn.

-

Srivijaya: Buddhist scholasticism radiated influence to China and India.

-

Philippines and Moluccas: ancestor and nature worship persisted within expanding trade cults.

-

Andamanasia: forest and sea spirits dominated local cosmologies; in Nias, megalithic monuments expressed mana and prestige, while Barus and Lambri absorbed early Islamic and Hindu-Buddhist influences through trade.

Adaptation and Resilience

Environmental management underpinned stability:

-

Angkor and Pagan mitigated monsoon variability through monumental waterworks.

-

Srivijaya redistributed goods across sea-lanes to balance local shortages.

-

Dual cropping systems of rice and root crops across island groups buffered climatic stress.

-

Barus and Lambri diversified trade in camphor, elephants, and aromatics, ensuring prosperity despite Srivijaya’s decline.

-

Coastal and island polities rebuilt quickly after storms through kin-based labor and inter-port reciprocity.

Long-Term Significance

By 1107 CE, Southeast Asia had matured into a dual civilization system of global reach:

-

Mainland empires—Angkor, Pagan, Lý Vietnam, and Champa—anchored monumental agrarian states powered by irrigation and religion.

-

Insular maritime realms—Srivijaya, Java, Sulawesi, and the Spice Islands—commanded trade networks that bridged the Indian Ocean and the South China Sea.

-

Andamanasia linked this world to the broader Indian Ocean economy, with Barus and Lambri emerging as cosmopolitan ports.

Together, these societies made Southeast Asia the pivotal hinge of Afro-Eurasian exchange, a zone where rice fed empires, spices enriched merchants, and monumental faiths rose from the wealth of land and sea alike.

People

Groups

- Hinduism

- Mon people

- Khmer people

- Vietnamese people

- Tai peoples, or Thais

- Buddhism

- Buddhists, Theravada

- Cham people

- Malays, Ethnic

- Buddhism, Mahayana

- Srivijaya, Malay kingdom of

- Champa, Kingdom of

- Khmer Empire (Angkor)

- Bamar or Burmans

- Mon Kingdoms

- Pagan (Bagan), Kingdom of

- Ngô dynasty

- Chinese Empire, Pei (Northern) Song Dynasty

- Champa, Kingdom of

- Dai Viet, Kingdom of

Topics

Commodoties

- Weapons

- Glass

- Oils, gums, resins, and waxes

- Grains and produce

- Textiles

- Ceramics

- Strategic metals

- Salt

- Slaves

- Lumber

- Aroma compounds

- Spices

Subjects

- Commerce

- Architecture

- Watercraft

- Painting and Drawing

- Environment

- Faith

- Government

- Custom and Law

- Metallurgy