Southeast Asia (909 BCE – 819 CE): …

Years: 909BCE - 819

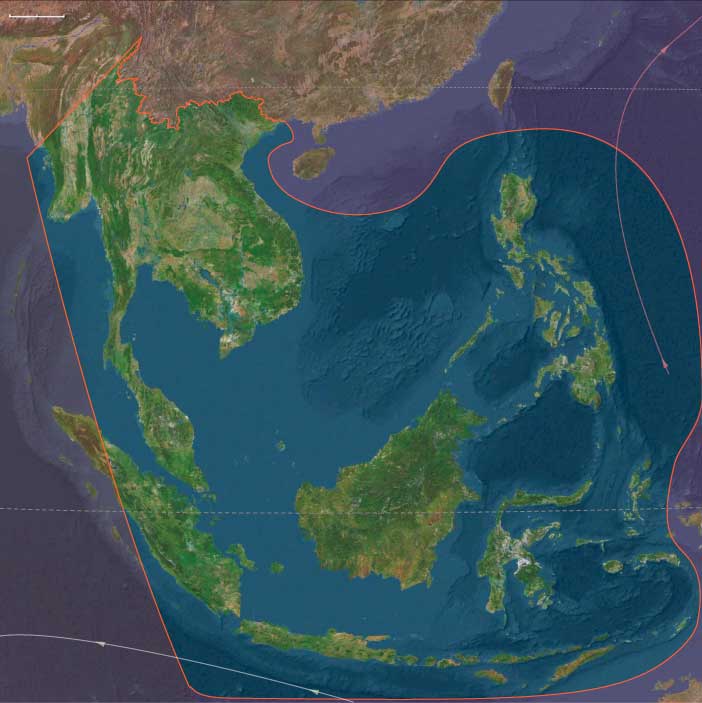

Southeast Asia (909 BCE – 819 CE): Monsoon Networks, Bronze Drums, and the Birth of Maritime Kingdoms

Regional Overview

By the dawn of the first millennium BCE, Southeast Asia had already begun to crystallize as the great crossroads of the Old World tropics.

Inland, the rice kingdoms of the Mekong, Chao Phraya, and Red River valleys emerged from the metallurgy and village confederations of the Bronze–Iron Age.

Seaward, the Andaman–Malay–Sumatran and Philippine–Bornean worlds turned the monsoon into an empire of routes, connecting India, China, and Oceania.

The entire region was defined by rhythm — the breathing of wind and water — in which farming, trade, and belief all synchronized to the turning of the monsoon.

Geography and Environment

The geography of Southeast Asia forms two great environmental theaters.

On the mainland, broad alluvial plains—Mekong, Chao Phraya, Irrawaddy, Red River—fed dense populations, while surrounding hills and plateaus nurtured metals and forest goods.

The insular and peninsular zones, stretching from the Malay Peninsula to Java, Sumatra, Borneo, Sulawesi, and the Philippine arcs, fused equatorial rainforest with coral coasts and volcanic fertility.

Farther west, the Andaman–Nicobar–Aceh corridor linked Bay of Bengal and Indian Ocean worlds, its islands and capes functioning as the hinges between South and East Asia.

Climatically, a regular monsoon pattern dominated: rains from May to October, dry trade-wind seasons from November to April. This stability made intensive wet-rice cultivation possible and guaranteed predictable sailing cycles—the dual engines of Southeast Asia’s rise.

Societies and Political Development

Mainland Southeast Asia

In the first millennium BCE, Bronze Age chiefdoms such as the Dong Son culture of the Red River valley forged regional identities through warfare, metallurgy, and ceremony. Their massive bronze drums, decorated with solar and aquatic motifs, became symbols of power from Vietnam to Borneo.

By the early centuries CE, irrigated rice systems underpinned early proto-states:

-

Funan in the Mekong delta—an entrepôt absorbing Indian trade and ideas;

-

Dvaravati in the Chao Phraya basin—Mon-speaking city-states blending Buddhism and local animism;

-

early Cham centers along the central Vietnamese coast, the maritime ancestors of later Hindu–Shaiva kingdoms;

-

and upland polities in Myanmar and Laos that balanced trade, salt, and forest exchange.

These societies fused Indigenous agrarian traditions with Indic and Sinic influences carried by merchants, monks, and artisans, producing hybrid languages of kingship and ritual that would define the classical kingdoms of later centuries.

Insular and Maritime Southeast Asia

Across the seas, communities in Java, Sumatra, Borneo, Sulawesi, and the Philippines evolved from Lapita-descended or Austronesian roots into settled horticultural and trading societies.

By the early first millennium CE, Iron-Age ports and coastal chiefdoms had appeared, their rulers mediating between inland farmers and overseas merchants.

On the Malay Peninsula, small harbors such as Kedah and Tambralinga became staging points for India–China traffic.

In Sumatra, fertile volcanic valleys and river deltas supported rice and pepper cultivation, while estuarine towns gathered forest resins, camphor, and gold.

In the Philippines, barangay polities combined boat-based clans with agricultural villages, forming fluid, maritime societies.

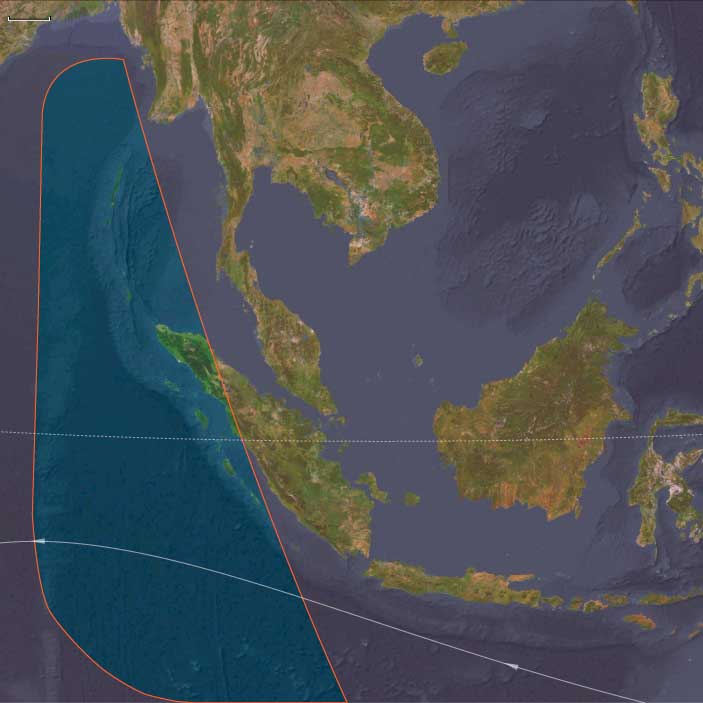

Andamanasia

At the western margin, Andamanasia—the Andamans, Nicobars, and northern Sumatran islands—was a liminal zone where Austronesian voyagers, Bay-of-Bengal traders, and forest foragers met.

Aceh and Nias sustained canoe chiefdoms trading resin, shells, and turtle shell for iron and beads from India; the Nicobars became vital relay stations between Sri Lanka and the Malay world.

The Andamans, by contrast, preserved independent hunter-gatherer cultures, holding their forests and reefs against encroachment.

Economy and Exchange

Everywhere, rice was the foundational crop, but economic vitality lay in diversity: rice in the floodplains, millet and tubers in uplands, sago and coconut in the islands, and marine protein along every coast.

Metals—bronze and later iron—spread from mining centers in northern Vietnam and central Thailand through trade networks that reached Sumatra and Java.

The monsoon trade carried spices, resins, camphor, tin, gold, and forest products westward toward India and the Mediterranean, and brought textiles, beads, and ceramics eastward in return.

Between these circuits, the maritime Austronesian seafarers of Borneo, the Philippines, and the Nicobars acted as indispensable intermediaries.

Technology and Material Culture

Iron tools and weapons revolutionized cultivation and warfare, enabling larger fields and more durable architecture.

Pottery traditions diversified; weaving and dyeing reached new complexity.

In navigation, plank-built outrigger canoes evolved into ocean-worthy ships using stitched or doweled planking and early lateen-type sails.

Bronze drums, metal jewelry, and stone statuary embodied both artistry and cosmology—objects that spoke of rain, fertility, and solar power.

Belief and Symbolism

Spiritual life blended animism, ancestor worship, and cosmic dualism with imported Hindu-Buddhist and Chinesecosmologies.

Mountain peaks and rivers were divine; kingship was a sacred covenant between the fertility of land and the order of heaven.

In the islands, sea gods and canoe ancestors received offerings before voyages; in the deltas, spirits of rice and water guarded every harvest.

Temples, bronze drums, and standing stones were not only monuments but acoustic instruments of faith—their sound bridging human and divine worlds.

Adaptation and Resilience

Southeast Asian societies mastered monsoon risk through diversification and redundancy. Double cropping, tank irrigation, and arboriculture mitigated drought.

Trade dualities—coast and interior, wet and dry season—created flexible economies.

When flood or famine struck one zone, maritime mobility rerouted supply and ritual obligation ensured redistribution.

This environmental intelligence, codified in both custom and cosmology, sustained the region’s balance between land and sea.

Regional Synthesis and Long-Term Significance

By 819 CE, Southeast Asia stood as a mature interface between the agrarian civilizations of the Asian continent and the maritime worlds of the Indian Ocean and Pacific.

Its mainland river states were consolidating bureaucratic power through irrigation and writing, while its island chiefdoms managed global trade routes that would soon nurture the empires of Srivijaya and Angkor.

To the west, Andamanasia remained the connective hinge—a patchwork of forager enclaves and canoe polities linking two oceans.

The region’s unity lay not in empire but in pattern: monsoon cycles, rice terraces, and sea lanes repeated across thousands of kilometers.

Its natural divisions—continental floodplains, equatorial archipelagos, and coral-fringed channels—explain why Southeast Asia divides so clearly into its Southeastern and Andamanasian subregions, each a reflection of the other: one grounded in the earth, the other in the sea.

Groups

- Mon people

- Hinduism

- Dong Son culture

- Sa Huynh culture

- Vietnamese people

- Tai peoples, or Thais

- Buddhism

- Buddhists, Theravada

- Pyu city-states

- Malays, Ethnic

- Cham people

- Funan, Kingdom of

- Buddhism, Mahayana

- Tarumanagara, or Taruma Kingdom

- Dvaravati, Mon Kingdom of

- Sri Ksetra, Kingdom of

- Chenla Kingdom

- Lavo, Mon Kingdom of

- Srivijaya, Malay kingdom of

- Champa, Kingdom of

Topics

Commodoties

- Weapons

- Gem materials

- Oils, gums, resins, and waxes

- Grains and produce

- Strategic metals

- Salt

- Lumber

- Aroma compounds

- Spices

Subjects

- Commerce

- Architecture

- Watercraft

- Painting and Drawing

- Environment

- Government

- Custom and Law

- Metallurgy