Southeast Asia (7,821 – 6,094 BCE): Early …

Years: 7821BCE - 6094BCE

Southeast Asia (7,821 – 6,094 BCE): Early Holocene — Rivers of Forest, Seas of Abundance

Geographic & Environmental Context

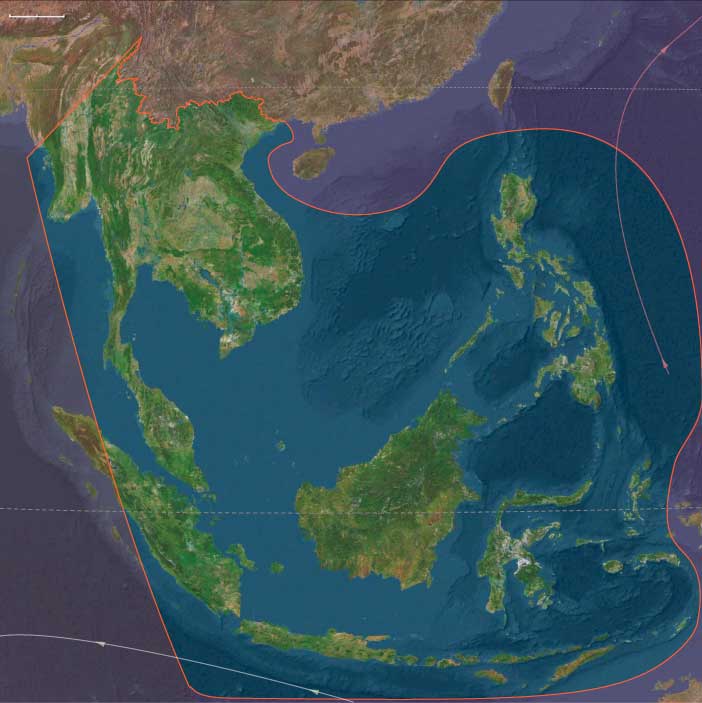

During the Early Holocene, Southeast Asia—encompassing the mainland river systems of the Irrawaddy, Chao Phraya, Mekong, and Red River, and the island worlds of the Malay Archipelago, Philippines, and eastern Indonesian seas—was a region reborn.

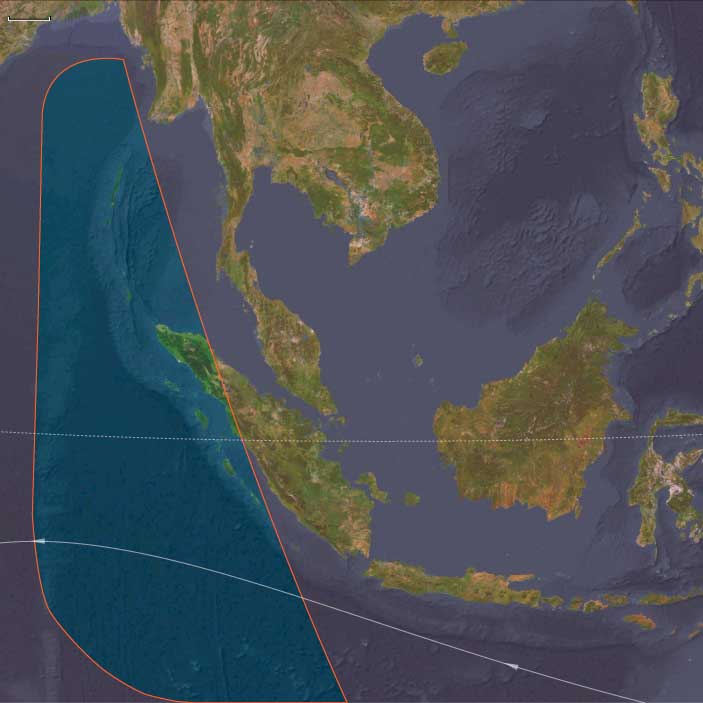

As postglacial seas flooded the Sunda Shelf, the coastlines of Sumatra, Java, Borneo, and the Malay Peninsula retreated to near-modern outlines, transforming river valleys into estuaries and mangrove deltas, and isolating upland populations as new islands formed.

From the rainforest interiors of Borneo and Sulawesi to the reef-fringed Nicobars and Sulu seas, the region entered an age of ecological plenty, where rising seas connected rather than divided, and rivers became arteries of settlement and exchange.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

The Holocene thermal optimum brought warm, humid, and stable monsoon conditions across tropical Asia.

-

Rainforests and mangroves expanded to their maximum historical extent.

-

Floodplains of the Mekong, Irrawaddy, and Chao Phraya rivers spread under sustained seasonal inundation, replenishing soils and fisheries.

-

Coral reefs and seagrass beds flourished in calm, nutrient-rich coastal waters.

-

Monsoons were reliable and moderate, fostering continuous forest growth and a rich mosaic of terrestrial and marine habitats.

This climatic equilibrium allowed for both forest intensification and maritime adaptation, setting the stage for Southeast Asia’s dual identity as a region of land-rooted and sea-linked societies.

Subsistence & Settlement

Across both mainland and island environments, broad-spectrum forager communities became increasingly semi-sedentary, clustering near stable water and forest edges:

-

Mainland river valleys and deltas: People lived along terraces and karst margins, combining fishing, hunting, and foraging with incipient plant tending. They harvested nuts, tubers, rice precursors (Oryza rufipogon), and pulses, along with fish, shellfish, deer, and pigs.

-

Island interiors (Borneo, Sumatra, Sulawesi): Forest foragers practiced sago and palm management, maintained tuber patches, and expanded nut collection (Canarium, Pandanus).

-

Coastal and estuarine zones: Populations exploited shellfish banks, coral reef fish, sea turtles, and mangroves, building large shell middens and seasonal fishing stations.

-

Philippines–Molucca–Sulawesi arcs: Mixed sago–taro economies combined with rich reef foraging; canoe settlements began appearing in estuarine lagoons.

These communities were not yet agriculturalists, but their deliberate replanting and niche management blurred the line between foraging and cultivation.

Technology & Material Culture

Material innovation was swift and adaptive:

-

Ground-stone adzes and axes became widespread for woodworking and forest clearance.

-

Basketry, cordage, and nets enabled efficient fishing and food transport.

-

Canoes, carved from single logs, expanded the mobility of estuarine and coastal groups, connecting rivers and islands into continuous cultural landscapes.

-

Pottery, emerging from southern China and northern Vietnam, reached the Red River delta by the end of this period, marking the earliest wave of ceramic use in mainland Southeast Asia.

-

Shell ornaments and bone tools—awls, points, hooks—appear in burial contexts, indicating social signaling and ritual activity.

Movement & Interaction Corridors

The Early Holocene saw the birth of Southeast Asia’s river–sea mobility system:

-

Mainland rivers (Irrawaddy, Mekong, Red) served as internal highways, connecting highland forest foragers with coastal lagoon dwellers.

-

Maritime corridors linked the Philippines, Borneo, Sulawesi, and the Moluccas, forming early canoe routes that anticipated Austronesian seafaring millennia later.

-

The Nicobar–Andaman–Aceh arc in Andamanasia functioned as a bridge between South Asia and the Indonesian world, distributing resin, shell, and fiber goods along coasts.

Through these networks, exchange and kinship began to span entire ecological zones—forest, river, coast, and sea.

Cultural & Symbolic Expressions

Ritual and ancestry were grounded in the land–water interface:

-

Cave burials and shelters—in Vietnam, Laos, and Thailand—yield ornaments, pigments, and bone tools, suggesting enduring ties to ancestral places.

-

Shell-midden feasting sites along coasts served as both ritual and communal arenas, marking seasonal abundance and renewal.

-

Rock art and pigment panels, depicting animals, boats, and hand stencils, continued traditions stretching back to the Pleistocene, linking memory, myth, and environment.

Spiritual life revolved around river spirits, forest abundance, and the recurring bounty of the tide.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

Early Holocene Southeast Asians achieved resilience through mobility, ecosystem diversity, and multi-resource integration:

-

Seasonal shifts between upland foraging and lowland fishing buffered against monsoon variability.

-

Sago groves, nut trees, and taro patches acted as “planted insurance,” ensuring dependable yields.

-

Canoe-linked exchange distributed surpluses and resources across ecological zones.

-

Arboriculture and controlled burning maintained forest mosaics, supporting both hunting and plant management.

These strategies created a stable human–environment symbiosis, capable of absorbing climate fluctuation without crisis.

Long-Term Significance

By 6,094 BCE, Southeast Asia had entered its Holocene equilibrium of diversity and connection.

Across river valleys, islands, and reefs, forest villagers and canoe foragers had forged economies that blended broad-spectrum subsistence with early forms of plant management and inter-island voyaging.

This epoch laid the foundations for later rice agriculture, arboriculture, and maritime exchange—systems that would turn Southeast Asia into the world’s great crossroads of land and sea.

The Early Holocene thus represents the deep beginning of the region’s ecological pluralism—a landscape where water, forest, and people learned to thrive together.