Southeast Asia (6,093 – 4,366 BCE): Middle …

Years: 6093BCE - 4366BCE

Southeast Asia (6,093 – 4,366 BCE): Middle Holocene — Rivers, Gardens, and the Expanding Sea

Geographic & Environmental Context

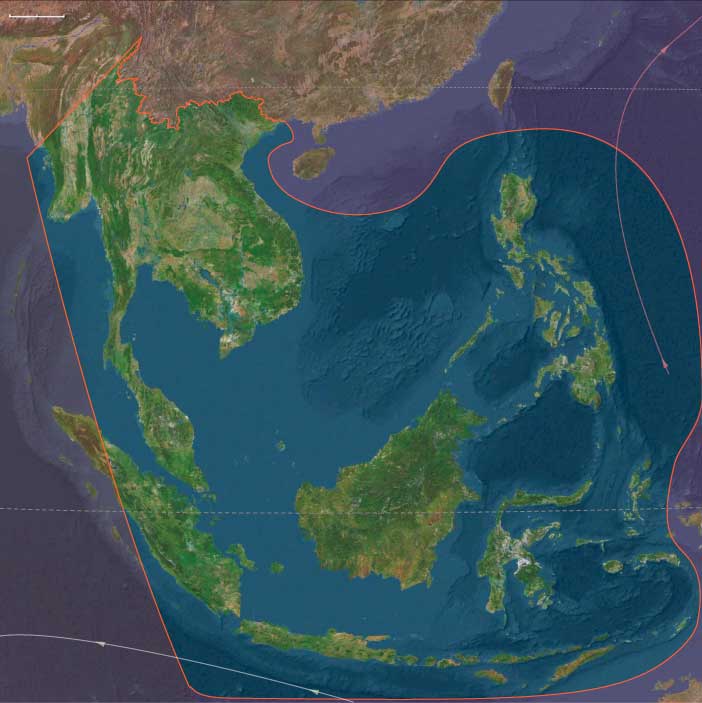

During the Middle Holocene, Southeast Asia—spanning the river plains of the Mekong, Chao Phraya, Irrawaddy, and Red River to the volcanic and forested archipelagos of Indonesia and the Philippines—entered a period of profound ecological and cultural integration.

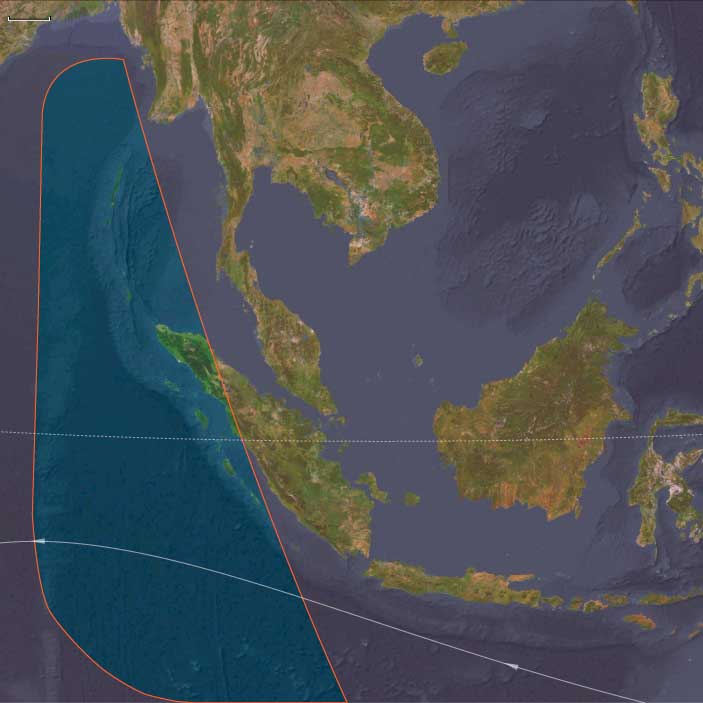

Sea levels rose to near-modern highstands, transforming low-lying basins into fertile deltas and coastal plains into estuarine mosaics. The Malay Peninsula, Sumatra, Java, Borneo, and Sulawesi became richly forested maritime zones surrounded by coral reefs and mangrove margins, while the Andaman and Nicobar Islands and Nias–Mentawai chain formed a natural bridge between South and East Asia.

By 5000 BCE, this environment had become one of Earth’s most productive ecotones—a region of monsoon-fed fertility and maritime connectivity, where rivers and seas worked together to sustain new patterns of settlement, subsistence, and exchange.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

The Hypsithermal warm phase reached its full expression. Monsoon rains were abundant and dependable, swelling the great deltas and feeding rice-friendly floodplains.

In the island world to the south and east, volcanic soils remained perpetually replenished, while heavy rainfall supported dense evergreen forest and freshwater wetlands.

Coastal regions experienced dynamic shoreline change as sea-level highstands widened estuaries and drowned river mouths, creating new estuarine nurseries for fish and shellfish.

These stable, humid conditions promoted the spread of early cultivation and arboriculture, encouraging permanent settlement and interregional trade.

Subsistence & Settlement

Across mainland and island Southeast Asia, mixed economies of farming, foraging, and fishing flourished.

-

Mainland river valleys saw the first domesticated rice and millet systems, especially in the lower Mekong and Red River basins. Villages of stilted houses and ceramic storage pits emerged along levees and floodplain ridges.

-

Island Southeast Asia developed proto-horticultural systems focused on taro, yam, banana, and breadfruit, often paired with nut-bearing and fruit trees—precursors to the orchard–garden mosaics of later Austronesian culture.

-

Coastal populations relied on reef, lagoon, and mangrove fisheries, with tidal weirs and canoe-based collection of shellfish and crustaceans.

-

In Andamanasia, islanders cultivated taro and yam within forest clearings, while sustaining foraging traditions and elaborate inter-island exchange.

The result was a continuum of economies—rice-field to reef-flat, garden to mangrove—that adapted seamlessly to monsoonal rhythms.

Technology & Material Culture

Technological innovation accelerated across the region:

-

Pottery diversified into cord-marked and impressed styles, suited for cooking, storage, and ceremonial use.

-

Ground-stone adzes and barkcloth beaters signaled advanced woodworking and textile production.

-

Early spindle whorls and loom weights point to nascent weaving.

-

In the islands, outrigger and dugout canoes appeared—especially in the Philippines–Sulawesi–Molucca sphere—permitting reliable travel across channels and among islets.

-

Obsidian and stone tools moved through expanding maritime circuits, establishing the foundations of the regional trade web that would later unite Southeast Asia with Melanesia and the Pacific.

Movement & Interaction Corridors

Southeast Asia became a crossroads of riverine and maritime mobility:

-

Inland routes followed the Mekong, Irrawaddy, and Red River valleys, spreading rice cultivation, stone-working, and ceramics across the mainland.

-

Coastal corridors linked the Malay Peninsula and Sumatran coasts with Java, Borneo, and the Philippines, forming a seamless maritime frontier.

-

Obsidian and shell exchange bound the Sulawesi–Molucca–Ceram–Halmahera arc to distant islands, while Andaman–Nicobar–Nias–Mentawai voyagers forged kinship alliances through canoe exchange and ritual feasts.

These movements gave rise to proto-Austronesian linguistic and cultural diffusion, the first step toward the trans-Pacific dispersals of later millennia.

Cultural & Symbolic Expressions

Cultural life centered on ancestors, feasting, and waterborne ritual.

-

Burials in ceramic jars or stone-lined pits suggest emerging ideas of lineage and continuity.

-

Shell ornaments, beads, and spindle whorls adorned the living and accompanied the dead, expressing wealth and identity.

-

Canoe imagery—in carved prows and ceremonial markings—reflected both spiritual symbolism and practical mastery of the sea.

-

Ritual feasts, held at planting or harvest times, celebrated the unity of clan and environment, strengthening alliances across rivers and straits.

These patterns reveal an already sophisticated maritime cosmology in which water, movement, and ancestry were inseparable.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

Communities maintained stability through ecological diversification. Wet-field cultivation, dry-field gardens, and fisheries complemented one another, ensuring food security amid monsoon variability.

Arboriculture protected soil fertility, while coastal mangroves and reefs absorbed storm impact. In the islands, canoe alliances functioned as social insurance, distributing surplus food and goods after floods, droughts, or volcanic events.

This adaptive flexibility produced a resilient cultural ecology, capable of absorbing environmental shocks without systemic collapse.

Long-Term Significance

By 4,366 BCE, Southeast Asia had become a crucible of innovation—a region where horticulture, rice agriculture, pottery, textile craft, and seafaring coalesced into enduring traditions.

Mainland farmers and island navigators forged the first interlinked continental–maritime civilization, grounded in river fertility and oceanic mobility.

These centuries established the environmental, technological, and cultural foundations for the later Austronesian expansion and the complex trading societies of the Neolithic and Bronze Age tropics.

Southeast Asia thus entered history not as a periphery but as the dynamic heart of early human adaptation to land and sea—a region where agriculture met the ocean, and the canoe became civilization’s first enduring vessel.