Southeast Asia (49,293 – 28,578 BCE): Upper …

Years: 49293BCE - 28578BCE

Southeast Asia (49,293 – 28,578 BCE): Upper Pleistocene I — Sundaland Continents, Island Worlds, and the Dawn of Rock Art

Geographic & Environmental Context

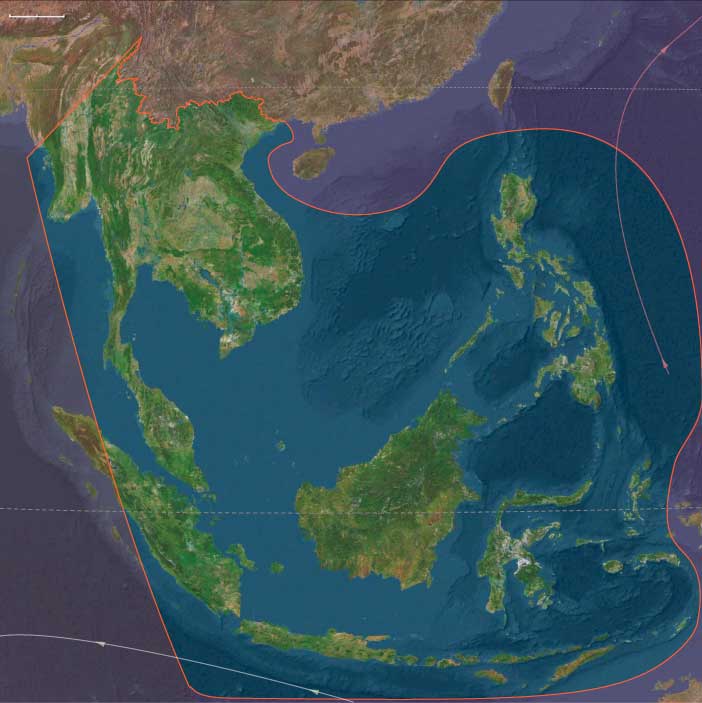

At the height of the Late Pleistocene glacial world, Southeast Asia presented two contrasting landscapes — the broad, continental plains of Sundaland and the fragmented islands of Wallacea and Andamanasia — together forming one of the planet’s richest and most diverse human realms.

-

Sundaland: With sea level 50–120 meters below present, the exposed shelf united Sumatra, Java, Borneo, and the Malay Peninsula into a single subcontinent threaded by enormous rivers (paleo-Mekong, Mahakam, Kapuas, Brantas, Musi). Its coastlines stretched hundreds of kilometers beyond today’s shores, forming wide savanna–forest mosaics, mangrove-fringed estuaries, and lagoons teeming with life.

-

Wallacea: Beyond the drowned shelf lay Sulawesi, the Moluccas, Banda, Halmahera, Timor, and the Philippines—a chain of volcanic and limestone islands divided by deep channels marking the Wallace Line. These crossings demanded deliberate navigation and early maritime technology.

-

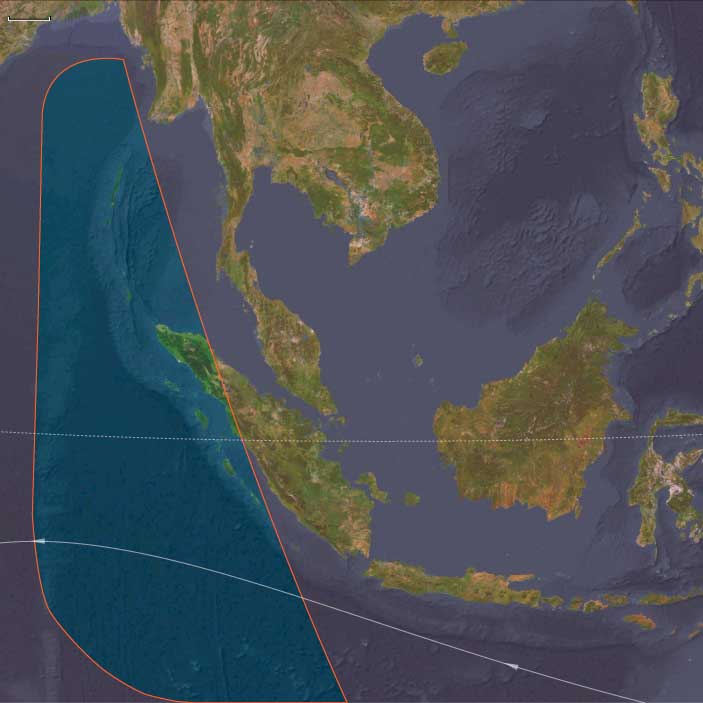

Andamanasia: To the northwest, the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, together with Aceh’s offshore arcs (Simeulue–Nias–Mentawai), Preparis–Coco, and the Cocos (Keeling) Islands, formed isolated forested refugia edging the exposed Sunda shelf. Their reefs, mangroves, and turtle beaches stood largely unpeopled but ecologically robust.

This region, straddling the equatorial monsoon belt, offered every possible habitat: mountains, caves, mangroves, coral reefs, and inland plains—each a seasonal hub for late Pleistocene foragers.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

-

Early Period (49–40 ka): Alternating warm–wet and cool–dry pulses governed by orbital forcing and monsoon strength. Forests waxed and waned, while lower sea levels extended savannas across exposed shelf flats.

-

Mid–Late Period (40–30 ka): Cooler, drier glacial trend; rivers incised deeper valleys, and interior lakes and wetlands shrank. On Sundaland, open woodlands and grasslands expanded, while the monsoon weakened and the dry season lengthened.

-

Approach to the LGM (after 30 ka): Intensified aridity inland; coastal productivity remained high as cold upwelling zones enriched fisheries. In Wallacea and Andamanasia, rainfall persisted in volcanic uplands and cloud-forest refuges, sustaining biodiversity through the glacial maximum.

These climatic oscillations required mobility and ecological flexibility, drawing humans toward coasts and river corridors where food remained predictable.

Human Societies and Lifeways

Sundaland Foragers

-

Population & Organization: Small, mobile bands of hunter–fishers numbering a few dozen individuals, moving seasonally between river valleys, forests, and estuaries.

-

Subsistence:

• Terrestrial: red deer, wild cattle (banteng), pigs, and forest birds; fruit, tubers, nuts, and honey.

• Aquatic: riverine fish, turtles, mollusks, and estuarine shellfish.

• Fire management maintained patchy mosaics that attracted game and improved travel routes. -

Settlements: Open camps along paleo-rivers and karstic caves (Lang Rongrien, Niah, Tabon) served as wet- and dry-season bases.

Wallacean Islanders

-

Maritime Expansion:

Short but deliberate crossings linked Bali–Lombok, Sulawesi, the Moluccas, and the Philippines. Voyagers likely used bamboo rafts or dugout craft, already capable of island-hopping across swift straits. -

Economy:

Coastal and reef exploitation dominated: fish, shellfish, turtles, and seabirds; inland forests provided sago palms, fruits, and nuts. -

Symbolism:

The world’s earliest known figurative rock art—hand stencils and painted animals in Sulawesi and Borneo (≥40,000 BP)—emerged here, marking one of humanity’s earliest symbolic revolutions.

Andamanasian Refugia

-

Status: Probably uninhabited or sparsely visited; nearby shelf coasts were rich in mangroves, turtles, and seabirds.

-

Role: Served as ecological storehouses—dense forests and reefs sustaining species that would repopulate coastlines when sea levels rose.

Technology & Material Culture

Across the region, technological diversity mirrored environmental range:

-

Stone industries: Large flakes, blades, and denticulates; hafted spear points and knives. Toolkits adapted to mixed forest and aquatic settings.

-

Organic tools: Bone and shell awls, barbed points, and fish gorges; woven nets and basketry inferred from indirect evidence.

-

Pigment and ornament: Red ochre for body painting and adhesive binders; perforated shell, tooth, and bone beads as markers of identity and alliance.

-

Fire technology: Controlled burning reshaped landscapes for hunting and plant gathering.

-

Maritime engineering: Simple rafts or canoes allowed crossing of deep channels—among the earliest seafaring experiments on Earth.

Movement & Interaction Corridors

-

River Arteries: The paleo-Mekong, Mahakam, and Kapuas systems functioned as “interior highways,” linking uplands to the exposed shelf coastlines.

-

Maritime Crossings:

• Wallace Line passages—Bali–Lombok, Makassar Strait, Molucca gaps—connected hunter–gatherer populations despite fierce currents.

• Philippine corridors—Luzon–Visayas–Mindanao and the Sulu arc—fostered early trade in shell, pigment, and worked bone.

• Andaman–Nicobar chains paralleled the Sunda coastline, possibly sighted but not yet permanently occupied.

These overlapping networks formed the world’s earliest complex seascape of interaction, prefiguring Holocene navigation traditions.

Belief and Symbolism

Southeast Asian peoples by this time had developed a sophisticated symbolic world:

-

Cave and rock art in Sulawesi, Borneo, and Palawan reveal enduring mythic narratives—animals, hand stencils, and spirit figures linked to hunting and fertility.

-

Ochre rituals and bead ornaments signified personal and group identity.

-

Animistic cosmologies likely centered on water, rock, and ancestral spirits inhabiting caves, springs, and trees—beliefs that would echo in later Austronesian spiritual systems.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

Adaptation was rooted in mobility, flexibility, and knowledge sharing:

-

Ecological diversity—forests, coasts, savannas, and rivers—allowed resource substitution during climate downturns.

-

Fire and water mastery reshaped landscapes and improved predictability.

-

Distributed knowledge networks—oral mapping of water sources, seasonal winds, and fauna—anchored community resilience.

-

Littoral foraging provided a caloric safety net through the harshest glacial episodes.

These strategies ensured persistence through one of the most variable climatic regimes on Earth.

Long-Term Significance

By 28,578 BCE, Southeast Asia had achieved a remarkable cultural and ecological synthesis:

-

The Sundaland–Wallacea continuum fostered societies adept at both land-based and maritime living.

-

Rock art, ornamentation, and pigment use announced an enduring symbolic sophistication.

-

Island-hopping navigation and inter-band exchange forged the first Pacific seafaring tradition.

These foundations—broad-spectrum foraging, flexible mobility, and deeply symbolic worldviews—would underpin every later cultural transformation of the region, from Holocene coastal settlement to Neolithic agriculture and, millennia later, the great Austronesian voyaging dispersals that carried Southeast Asia’s legacy across the entire Pacific.