Southeast Asia (28,577 – 7,822 BCE): Late …

Years: 28577BCE - 7822BCE

Southeast Asia (28,577 – 7,822 BCE): Late Pleistocene–Early Holocene — Deglaciation, Island Worlds, and the Age of Painted Caves

Geographic & Environmental Context

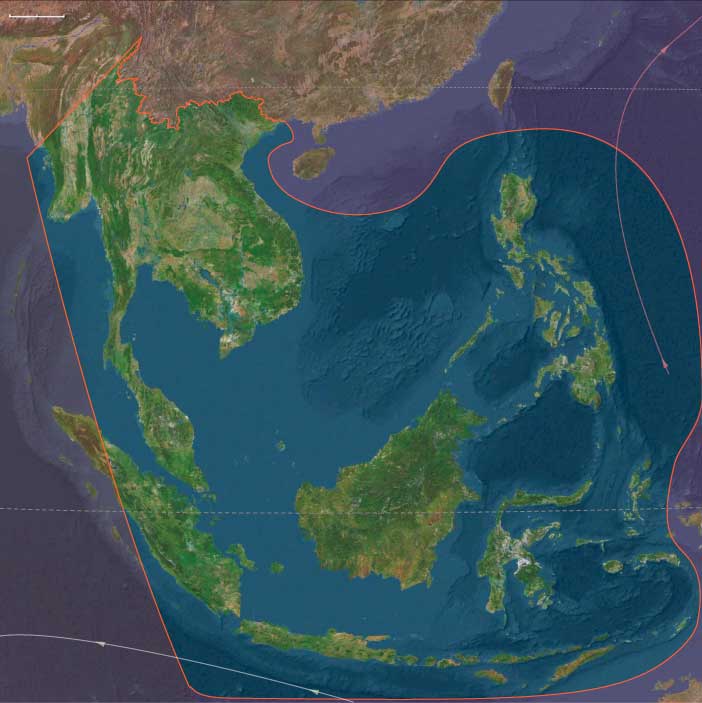

During the Late Pleistocene and early Holocene, Southeast Asia transformed from a single vast continent—the Sunda Shelf—into the world’s largest archipelagic region.

As glaciers melted and sea level rose more than 100 m, the ancient plains that once joined Sumatra, Borneo, Java, and the Malay Peninsula vanished beneath the sea.

By 8,000 BCE, the modern configuration of islands, peninsulas, and straits had formed, creating the fragmented landscapes that define Southeast Asia today.

Two great cultural-ecological spheres emerged:

-

Southeastern Asia (mainland and Sundaic islands: Myanmar, Thailand, Cambodia, Vietnam, Malaysia, Sumatra, Java, Borneo, Sulawesi, the Philippines, and surrounding seas) — a region of rock-shelter cultures, reef-foragers, and early voyagers.

-

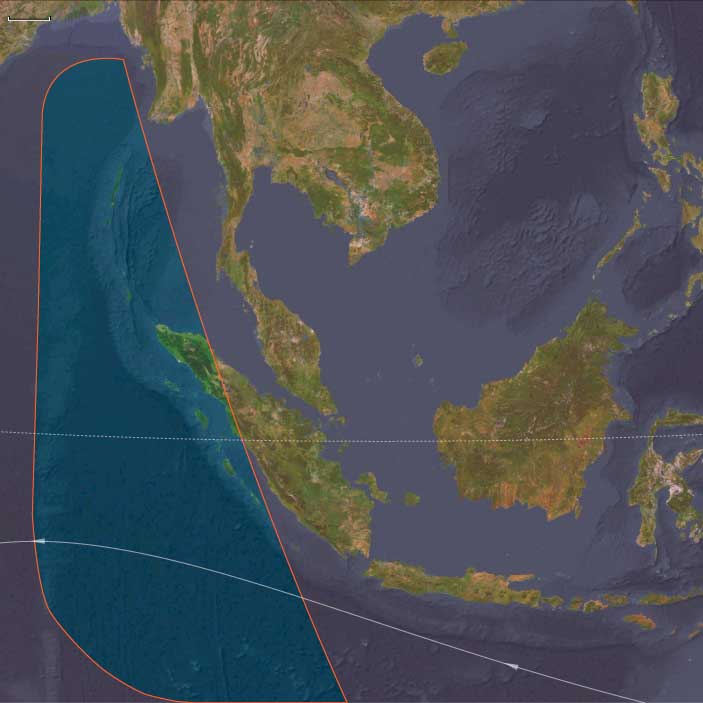

Andamanasia (Andaman–Nicobar–Aceh–Mentawai arc) — a bridge corridor between the Bay of Bengal and the eastern Indian Ocean, where island foragers first adapted to rising seas through mobility and exchange.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

The transition from the Last Glacial Maximum to the Holocene thermal optimum reshaped every ecosystem:

-

Last Glacial Maximum (c. 26,500 – 19,000 BCE): cooler, drier conditions contracted tropical forests; open grasslands dominated the Sunda Shelf; coasts extended hundreds of kilometers seaward.

-

Bølling–Allerød (c. 14,700 – 12,900 BCE): abrupt warming and intensified monsoons regenerated rainforests, flooded valleys, and boosted reef productivity.

-

Younger Dryas (12,900 – 11,700 BCE): a brief return to cooler, drier climates reduced forest cover and lowered rainfall; many groups pivoted toward coastal and riverine foraging.

-

Early Holocene (after 11,700 BCE): renewed warmth and humidity stabilized monsoons, expanded mangroves, and created the modern deltaic and island environments of the region.

The sea’s advance transformed the old Sundaic plains into the Java, South China, and Andaman Seas, generating new migration corridors and refuges.

Subsistence & Settlement

Late Pleistocene–Holocene communities practiced broad-spectrum foraging, balancing marine and terrestrial resources as coasts shifted:

-

Mainland & Sundaic islands:

Cave and rock-shelter settlements proliferated—Niah (Borneo), Lang Rongrien (Thailand), Tabon (Palawan)—where people hunted deer, pigs, and macaques; gathered tubers, nuts, and fruit; and harvested shellfish, reef fish, and turtles.

As shorelines retreated inland, estuarine fisheries and mangrove gathering replaced the vast riverine plains of the glacial period. -

Andaman–Nicobar–Aceh–Mentawai arc:

Canoe-borne foragers settled the Andaman and Nicobar Islands early, maintaining mixed forest–littoral economies of wild yams, deer, pigs, fish, and turtle.

Nicobars and Mentawais saw itinerant villages around lagoons and palm belts, while Aceh’s capes supported estuarine hunters and reef gleaners.

The Cocos and Preparis islets remained largely uninhabited but intermittently visited.

Across the region, settlements cycled between coastal and upland zones, tracking resource pulses through seasonal mobility.

Technology & Material Culture

Technological versatility matched the diversity of habitats:

-

Blade–microlith industries adapted to hunting and woodworking.

-

Ground-stone adzes and shell tools appeared for tree felling and canoe shaping.

-

Bone harpoons and fish gorges expanded marine exploitation.

-

Nets, baskets, and bark containers aided storage and mobility.

-

Ornaments in shell, bone, and stone expressed group identity, while ochre marked both body and rock.

-

The period’s most enduring legacy lay in Sulawesi’s cave art, where hand stencils and depictions of babirusas and deer-pigs—painted more than 40,000 years ago and renewed in this epoch—attest to a continuous symbolic tradition of exceptional depth.

Movement & Interaction Corridors

Rising seas did not isolate communities—they reorganized movement:

-

Philippines–Sulawesi–Moluccas–Banda arc: voyaging intensified along visible island chains; short open-sea hops of 50–100 km created one of the earliest sustained maritime networks on Earth.

-

Andaman–Nicobar–Aceh–Mentawai corridor: canoe routes linked rainforests and reefs, establishing exchange of shell, resin, and ochre long before later Austronesian expansion.

-

Mainland river valleys (Irrawaddy, Chao Phraya, Mekong, Red) remained arteries of movement, connecting highland hunters to emerging coastal fisheries.

In effect, Southeast Asia became a maritime crossroads, not a fragmented world.

Cultural & Symbolic Expressions

Symbolic life flourished amid environmental flux:

-

Cave art and engraving traditions expanded across Sulawesi, Borneo, and mainland karsts.

-

Ritual burials with ochre, shell ornaments, and pig or turtle offerings emphasized ancestry and connection to place.

-

Portable ornaments—beads, pendants, animal carvings—spread widely, perhaps marking alliance networks.

-

In Andamanasia, shell-midden cemeteries and ritual fires expressed continuity across generations as shorelines advanced.

The human imagination here turned environmental change into cosmology, reflecting a worldview of islands as living entities linked by sea and spirit.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

Adaptation relied on mobility, diversity, and exchange:

-

Coastal intensification—shellfish, reef fish, and turtle harvesting—buffered inland droughts during the Younger Dryas.

-

Forest knowledge systems diversified diets and materials; edible tubers, palms, and resinous trees provided fallback foods and technology.

-

Canoe voyaging maintained inter-island ties, reducing risk from local resource failure.

-

Populations tracked mangrove succession and coral growth, continuously resettling new lagoons as older coasts drowned.

The region’s peoples evolved a unique maritime–terrestrial dualism that would persist into later Holocene societies.

Long-Term Significance

By 7,822 BCE, Southeast Asia had become a world of islands, caves, and canoes—a landscape defined by water, art, and mobility.

-

Southeastern Asia saw its great painted caves, the flourishing of maritime foraging, and the first truly island-based societies.

-

Andamanasia established continuous human occupation across its archipelagos, anticipating later Indian Ocean seafaring.

The epoch’s legacy was both environmental and cultural: a blueprint for the seagoing economies and symbolic richness that would, millennia later, carry Austronesian speakers and their descendants across the Indo-Pacific.