Southern Indian Ocean (49,293–28,578 BCE): Upper Pleistocene …

Years: 49293BCE - 28578BCE

Southern Indian Ocean (49,293–28,578 BCE): Upper Pleistocene I — Glacial Frontiers and the Subantarctic Living Sea

Geographic & Environmental Context

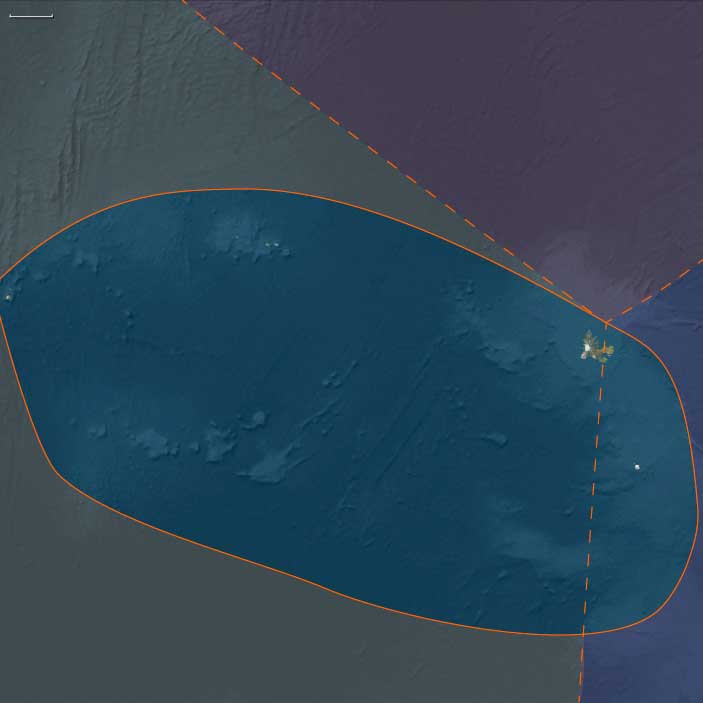

During the height of the last Ice Age, the Southern Indian Ocean world—composed of the Southeast Indian Ocean subregion (Kerguelen east of 70°E, Heard, and McDonald Islands) and the Southwest Indian Ocean subregion(western Kerguelen, the Îsles Crozet, and Prince Edward–Marion Islands)—stood as a scattered constellation of volcanic outposts astride the circumpolar current.

Together, these two subregions formed the northern ramparts of Antarctica’s climatic realm: bleak, wind-lashed, yet biologically exuberant. Their high plateaus and coastal shelves were carved by ice and pummeled by the Southern Ocean’s furious westerlies. Kerguelen, the “Great Southern Land” of the subantarctic, spanned nearly 7,000 square miles of basaltic uplands, glaciers, and fjorded coasts—dwarfing its neighbors. To the west, the Crozet and Prince Edward groups rose as serrated volcanic cones; to the east, Heard and McDonald smoldered on the oceanic horizon. Sea levels 60–90 m lower than today broadened their near-shore benches, but their cliffs and mountains ensured that even exposed shelves were narrow.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

Throughout this span, the Last Glacial Maximum gathered strength.

-

Atmosphere & Temperature: Mean annual temperatures were several degrees colder than today, and precipitation fell mostly as snow. Ice caps mantled Kerguelen’s highlands and the summits of Heard and Crozet.

-

Winds & Currents: The westerly storm belt intensified; katabatic outflow from Antarctica sharpened the pressure gradient, amplifying the “roaring forties” and “furious fifties.”

-

Ocean Systems: The Antarctic Circumpolar Current (ACC) tightened around the islands, churning nutrient-rich upwellings that fueled one of Earth’s great marine food webs.

-

Sea Level: Lower global sea level expanded intertidal zones and ice-free headlands but did little to change the islands’ rugged relief.

The result was an environment at once extreme and thriving—a cold oceanic oasis in which ice, wind, and water sustained a chain of life from krill to whale.

Ecosystems & Biotic Communities

Though uninhabited by humans, these islands pulsed with ecological energy.

-

Terrestrial life: Sparse subantarctic tundra—mosses, lichens, cushion plants, and graminoids—colonized lee slopes and moraines. On Kerguelen’s western plateaus and Heard’s lower benches, periglacial soils nurtured mats of hardy vegetation that trapped moisture and nitrogen from seabird guano.

-

Avifauna: Albatrosses, petrels, skuas, and penguins established immense rookeries, their cycles governed by ice advance and retreat.

-

Marine mammals: Seals and elephant seals hauled out on the few ice-free beaches; whales traced annual feeding migrations through the ACC’s plankton blooms.

-

Marine productivity: Krill, squid, and small pelagic fish flourished in cold upwelling zones, knitting together a trans-oceanic ecosystem that linked Antarctica, Africa, and Australasia.

These biological systems recycled nutrients with astonishing efficiency; seabird guano and seal carcasses fertilized soils, and winds redistributed minerals across the ocean surface—an unbroken loop of energy long before any human witness.

Human Absence and Global Context

Elsewhere across the planet, Upper Paleolithic peoples perfected blade industries, tailored clothing, and art traditions, but no seafarers had ventured this far south. The subantarctic islands lay well beyond the reach of any Pleistocene navigation system. Their extreme latitude, relentless weather, and lack of fuel or timber would have defeated even the most adaptable hunter-gatherers.

Their absence, however, highlights a global contrast: while Eurasian and African foragers filled temperate landscapes with symbols and settlements, the Southern Indian Ocean remained the great unpeopled wilderness, its only networks those of wind, current, and migration.

Movement & Interaction Corridors

Even without humans, the region was laced with biological highways:

-

The ACC carried nutrients and drifting plankton eastward around the world, feeding a continuous belt of marine life.

-

Migratory whales and seabirds followed these currents seasonally, moving between Antarctic feeding grounds and temperate breeding sites.

-

The islands themselves acted as stepping-stones for non-human travelers—rookeries, haul-outs, and rest sites—linking ecosystems thousands of kilometers apart.

These corridors, carved by wind and current, pre-figured the oceanic routes that human mariners would one day exploit.

Symbolic and Conceptual Dimensions

To the Ice-Age imagination, had these lands been known, they would have represented the edge of the habitable world—a mythic margin where ocean, ice, and sky merged. In reality they lay beyond any cultural horizon, silent witnesses to global climatic drama, unmarked by tools or fire.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

Across glacial cycles, these ecosystems displayed remarkable resilience:

-

Vegetation persisted in sheltered micro-refugia, recolonizing freshly deglaciated ground after each cold surge.

-

Seabirds and seals adjusted breeding sites in rhythm with ice extent.

-

Nutrient cycling remained intact through redundancy: if one rookery failed, others thrived along the current.

This flexibility forged an enduring ecological template that would persist into the Holocene and still defines the subantarctic today.

Transition Toward the Glacial Maximum

By 28,578 BCE, glaciers on Kerguelen and Heard had reached their broadest limits, and sea ice brushed the northern edge of the ACC. Yet life endured in astonishing abundance.

The Southern Indian Ocean, though untouched by humans, was already a complete, self-regulating world—a chain of volcanic fortresses girdling the planet’s coldest sea. Its twin subregions, Southeast and Southwest Indian Ocean, illustrate precisely the principle that unites The Twelve Worlds: even where no people walked, each subregion lived as its own coherent ecology, bound more closely to kindred zones across oceans than to any continental neighbor. When humanity finally reached these latitudes, the template for adaptation—ice, wind, nutrient, and endurance—was already written in the land itself.