Southwest Indian Ocean (49,293–28,578 BCE): Volcanic Arcs …

Years: 49293BCE - 28578BCE

Southwest Indian Ocean (49,293–28,578 BCE): Volcanic Arcs in the Subantarctic

Geographic & Environmental Context

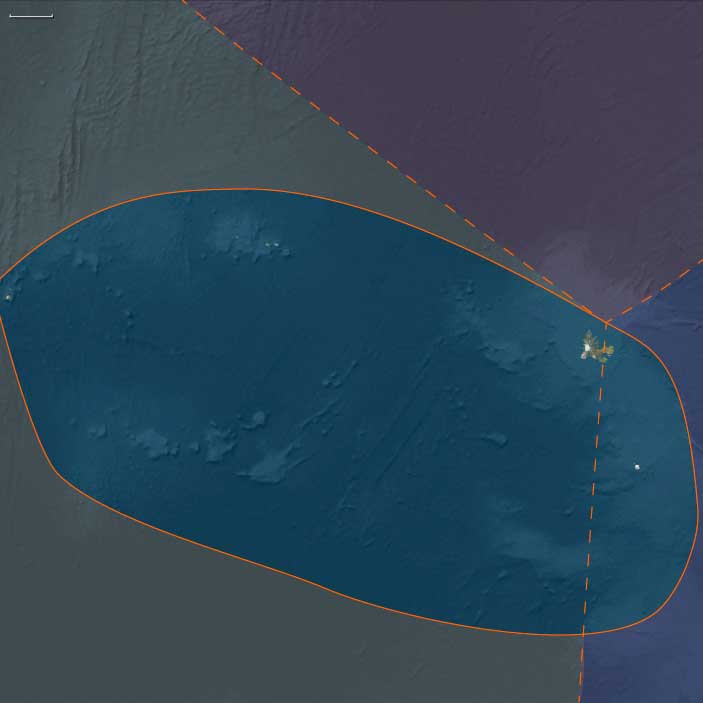

The subregion of Southwest Indian Ocean includes Kerguelen west of 70°E, the Îsles Crozet, Prince Edward Island, and Marion Island. These islands rise from the southern Indian Ocean in the storm-lashed belt of the subantarctic. Kerguelen’s western expanses formed the largest landmass of the subregion, with basaltic plateaus and glaciated valleys. The Îsles Crozet, scattered volcanic peaks, lay further west; Prince Edward and Marion Islands anchored the subregion’s southwestern corner. All were rugged, volcanic, and isolated, fringed by steep coasts and pummeled by westerly winds.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

This age coincided with the Last Glacial cycle. Sea levels lay 60–90 meters lower, exposing broader coastal shelves but leaving the islands’ steep relief largely unchanged. Temperatures were colder than today, with advancing glaciers on western Kerguelen and high volcanic plateaus across the Crozet and Prince Edward groups. Fierce katabatic winds from Antarctica mingled with circumpolar westerlies, intensifying storm tracks. Ocean waters were cooler, strengthening upwelling systems that enriched marine productivity around these volcanic arcs.

Subsistence & Settlement

Humans had not yet reached these islands. Their ecosystems, however, were rich. Subantarctic tundra vegetation—mosses, lichens, and cushion plants—established themselves in sheltered niches. Seabird colonies, especially petrels and albatrosses, blanketed cliffs, while penguins and seals occupied ice-free shores. Nutrient cycling from guano deposits fertilized soils, creating patches of biological richness amid volcanic barrenness. Offshore, whales, seals, and seabirds traced migratory corridors that linked these islands to Antarctica, southern Africa, and Australasia.

Technology & Material Culture

Although no people lived here, contemporaneous societies elsewhere in the world were advancing Upper Paleolithic toolkits, symbolic traditions, and survival strategies in cold climates. Had humans reached the subantarctic islands, survival would have required highly specialized technologies: insulated clothing, seaworthy vessels, and methods for exploiting marine mammals. The absence of such evidence underlines the extreme isolation of these islands during this age.

Movement & Interaction Corridors

The Southern Ocean circulation swept around these islands, carrying nutrients and sustaining immense food webs. Migrating whales passed seasonally, while seabirds and seals established transoceanic networks of rookeries and feeding grounds. These currents and corridors would one day make the islands strategic for human navigation, but in this age, they were highways only for nonhuman travelers.

Cultural & Symbolic Expressions

No human symbolic activity is tied to the Southwest Indian Ocean islands in this age. Globally, however, human groups were producing art, ornaments, and ritual sites, embedding meaning in landscapes far from these volcanic outposts. The islands themselves remained unknown and unimagined, lying outside the human cultural horizon.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

Life on these islands demonstrated resilience to glacial extremes. Vegetation survived in sheltered microhabitats, recolonizing deglaciated areas as climates fluctuated. Seabird and seal populations shifted breeding sites with changing ice coverage. The capacity of these ecosystems to reorganize under climatic stress foreshadowed the adaptive dynamics that would define their later ecological histories.

Transition

By 28,578 BCE, the glacial maximum was intensifying, with ice reaching peak expansion. The Southwest Indian Ocean islands remained untouched by human hands, yet ecologically vital within the subantarctic marine web. These volcanic arcs stood as stark, wind-battered sentinels, their environments shaped by ice, ocean, and storm.