Southeastern Asia (1252–1395 CE): Mongol Campaigns, Theravāda …

Years: 1252 - 1395

Southeastern Asia (1252–1395 CE): Mongol Campaigns, Theravāda Ascendancy, and Maritime Gateways

Geographic and Environmental Context

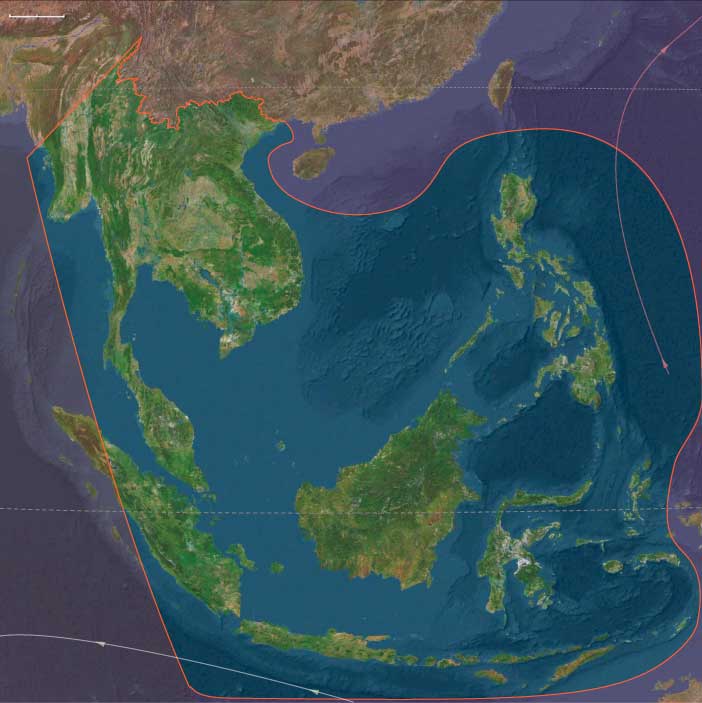

Southeastern Asia during this age encompassed southern and eastern Myanmar, Thailand, Cambodia, Laos, Vietnam, the Malay Peninsula, Sumatra (excluding Aceh and western offshore islands), Java, Borneo, Sulawesi, the Philippines, and the surrounding archipelagos—the Banda Molucca, Ceram, Halmahera, and Sulu groups.

A region of fertile river basins (Irrawaddy, Chao Phraya, Mekong, Red), volcanic highlands (Java, Sumatra), and reef-fringed archipelagos, it stood as the meeting point of the Indian Ocean and South China Sea, uniting Afro-Eurasian trade, faith, and diplomacy.

Climate and Environmental Shifts

The onset of the Little Ice Age (~1300 CE) brought fluctuating monsoons, variable rainfall, and heightened storm activity.

-

Mainland plains: large irrigation reservoirs buffered droughts.

-

Volcanic islands: Javanese terrace systems and Sumatran deltas sustained rich harvests.

-

Coastal zones: Vietnam and the Philippines faced frequent typhoons, while upland forests provided fallback resources.

Environmental challenges sharpened hydraulic innovation and maritime flexibility, anchoring the region’s resilience.

Mainland Polities

The Pagan Successor States (Burma)

The Pagan Empire declined after successive Mongol invasions (1277–1287 CE). In its wake arose:

-

Ava (Inwa): an inland power seeking to revive Burmese unity.

-

Hanthawaddy: a prosperous Mon-Buddhist state centered on Pegu, oriented toward maritime exchange.

-

Shan chiefdoms: fragmented upland domains that retained autonomy through fortified valleys.

Theravāda Buddhism endured as the cultural bond linking the successor states; pagoda construction and monastic networks reinforced continuity amid political fragmentation.

Angkor and the Khmer Realm (Cambodia)

Under Jayavarman VII (late 12th c.), Angkor reached monumental heights with temples such as Bayon and vast hydraulic works. Yet by the 14th century, the empire weakened:

-

Thai incursions from Sukhothai and Ayutthaya penetrated the northwest.

-

Maintenance of Angkor’s reservoirs faltered as population centers shifted southward toward the Tonlé Sap and Mekong.

Even as political power ebbed, Khmer artistry, Sanskrit inscriptions, and Theravāda conversion preserved Angkor’s cultural legacy across the Mekong basin.

Sukhothai and Ayutthaya (Thailand)

Founded c. 1238 CE, Sukhothai under King Ramkhamhaeng consolidated Thai power in the Chao Phraya valley. The king promoted Theravāda Buddhism from Sri Lanka, crafted an early Thai script, and styled himself a dhammaraja(“righteous ruler”).

By 1351, Ayutthaya had supplanted Sukhothai as the pre-eminent lowland kingdom, commanding trade along the Gulf of Siam. Its diplomatic reach extended to China and Lanka, marking the ascent of the classical Thai state that would dominate later centuries.

Lan Xang (Laos)

In 1353 Fa Ngum established the Kingdom of Lan Xang (“Million Elephants”), uniting Tai-Lao muang confederations across the upper Mekong.

Theravāda Buddhism became the royal creed, blending with pre-Buddhist spirit worship. Highland rice valleys, forest trade, and elephant capture sustained its economy. Though loosely centralized, Lan Xang defined the cultural heartland of Laos.

The Trần Dynasty (Vietnam)

The Trần dynasty (1225–1400) guided Đại Việt through both warfare and reform:

-

Repelled three Mongol invasions (1257, 1284–85, 1287–88), safeguarding independence from Yuan China.

-

Expanded irrigated rice cultivation and maritime trade from the Red River Delta.

-

Fostered a Confucian-Buddhist state: royal exams, monastic patronage, and flourishing art and poetry.

Vietnam emerged as a stable, literate, and bureaucratic kingdom, distinct yet connected to the Sinosphere.

Island and Maritime Realms

Majapahit (Java)

Founded in 1293 after defeating a Mongol expedition, the Majapahit Empire unified much of insular Southeast Asia through a network of tribute, alliance, and naval control.

Under Hayam Wuruk (r. 1350–1389) and prime minister Gajah Mada, Majapahit’s dominion spanned the Sunda Strait to the Moluccas, integrating Sumatra, Borneo, and the Malay Peninsula. The Nagarakretagama (1365) listed scores of tributary polities.

Hindu–Buddhist syncretism flourished at the capital Trowulan; temples such as Panataran embodied Majapahit’s cosmopolitan art. Massive jong ships plied the Indian Ocean, carrying spices, rice, and textiles.

Sumatra and the Malay Peninsula

After Srivijaya’s eclipse, regional polities such as Malayu (Jambi), Dharmasraya, and Pasai vied for control.

-

Malayu maintained inland river trade and gold exports.

-

Pasai, in northern Sumatra, became one of the earliest Muslim trading centers, patronizing Arabic inscriptions and mosques.

On the Malay Peninsula, ports like Tumasik (Singapura) thrived as transshipment hubs for Chinese and Indian goods. These early entrepôts laid the groundwork for Melaka’s later ascendancy.

Borneo, Sulawesi, and the Philippines

Inland Borneo communities exploited forest resins, camphor, and gold, while coastal chiefdoms developed around estuaries such as Brunei Bay.

Sulawesi’s maritime polities specialized in forest goods and sea trade; its seafarers were early masters of inter-island navigation.

In the Philippines, chiefdoms (barangay) exchanged gold, beeswax, and forest products with Chinese merchants. Early Islam began to spread into the Sulu Archipelago, while indigenous animist rituals persisted elsewhere.

The Spice Archipelagos (Moluccas and Banda)

The islands of Ternate, Tidore, Banda, and Ambon held the world’s only sources of cloves, nutmeg, and mace. Control of these lucrative commodities made them magnets for traders from Java, Sumatra, India, and Arabia.

Spice wealth sustained local dynasties whose alliances shifted between Majapahit, Malay, and Muslim traders—prefiguring the intense competition of later centuries.

Economy and Technology

Agriculture and Production

-

Rice agriculture formed the demographic core—intensive wet-rice systems in mainland deltas and Javanese terraces.

-

Cash crops: pepper, sandalwood, camphor, and forest resins supplied Indian Ocean markets.

-

Animal labor: elephants and buffalo powered transport and irrigation.

Trade and Maritime Networks

-

Majapahit controlled the Sunda Strait and Java Sea lanes.

-

Tumasik and Pasai acted as gateways between the Indian Ocean and South China Sea.

-

Philippine ports moved gold and aromatic goods northward to China.

-

Spice routes from Banda and the Moluccas linked to Java, India, and Arabia, woven into monsoon cycles that drove seasonal navigation.

Technology and Craftsmanship

-

Hydraulic works: Angkor’s reservoirs, Pagan’s canals, and Javanese terraces.

-

Shipbuilding: large multi-masted jong carried hundreds of tons of cargo.

-

Military tech: elephants in mainland armies; fire-rafts and boarding tactics in Javanese fleets.

-

Artisanal crafts: Khmer stone sculpture, Javanese batik, Vietnamese ceramics, and fine metalwork.

Belief and Symbolism

Religion and cosmology interlaced through syncretic adaptation:

-

Theravāda Buddhism—from Sri Lanka—spread through Sukhothai, Lan Xang, and the Pagan successor states, defining kingship as moral guardianship.

-

Mahayana Buddhism and Hinduism remained influential at Angkor and Majapahit, where deities Śiva and Buddha were worshiped jointly.

-

Vietnam’s Confucianism emphasized bureaucratic virtue within a Buddhist frame.

-

Early Islam advanced along Sumatra’s coast through Sufi networks and merchant settlements.

-

Indigenous beliefs—animism, ancestor worship, and ritual ecology—continued in islands and uplands, merging gradually with imported faiths.

Temples, mosques, and spirit shrines coexisted in the same landscapes, symbolizing the region’s cultural pluralism.

Adaptation and Resilience

-

Diversified agriculture: combined wet-rice, dryland crops, and arboriculture to withstand erratic monsoons.

-

Political realignment: as Pagan and Angkor declined, Ayutthaya, Lan Xang, and Majapahit rose, ensuring regional stability.

-

Maritime redundancy: when one port waned, trade shifted seamlessly to another.

-

Syncretic faith: Hindu-Buddhist-Islamic blending softened transitions and fostered cultural integration.

Long-Term Significance

By 1395 CE, Southeastern Asia embodied both transformation and continuity:

-

Majapahit stood as the last great Hindu-Buddhist maritime empire, commanding tribute and trade across the archipelago.

-

Ayutthaya and Lan Xang anchored Theravāda Buddhism on the mainland.

-

Vietnam’s Trần dynasty solidified independence through Confucian-Buddhist governance.

-

Early Muslim ports like Pasai and Aceh hinted at the coming Islamic era.

-

Spice islands and Malay ports maintained the region’s centrality in Afro-Eurasian exchange.

Through shifting kingdoms and climatic challenge, Southeastern Asia remained a vibrant hinge of trade and faith—its deltas, forests, and seas sustaining a civilization of profound adaptability and maritime genius.

People

Groups

- Hinduism

- Mon people

- Khmer people

- Vietnamese people

- Tai peoples, or Thais

- Buddhism

- Buddhists, Theravada

- Cham people

- Malays, Ethnic

- Buddhism, Mahayana

- Kedah, Malay state of

- Srivijaya, Malay kingdom of

- Melayu Kingdom

- Champa, Kingdom of

- Khmer Empire (Angkor)

- Bamar or Burmans

- Mon Kingdoms

- Pagan (Bagan), Kingdom of

- Ngô dynasty

- Shan people

- Champa, Kingdom of

- Chola Empire

- Kediri, Kingdom of

- Dai Viet, Kingdom of

- Mongols

- Chinese Empire, Nan (Southern) Song Dynasty

- Mongol Empire

- Sukhothai (Siam), Thai state of

- Chinese Empire, Yüan, or Mongol, Dynasty

- Shan States

- Majapahit Empire

- Lanna, or Lan Na (Siam), Thai kingdom of

- Ayutthaya (Siam), Thai state of

- Lan Xang, Kingdom of

- Sukhothai (Siam), Thai vassal kingdom of

Topics

- Mongol Conquests

- Mongol invasions of Vietnam

- Mongol Invasion of Burma, or Mongol-Burmese War of 1277-87

- Little Ice Age, Warm Phase I

- Little Ice Age (LIA)

Commodoties

- Weapons

- Glass

- Oils, gums, resins, and waxes

- Grains and produce

- Textiles

- Ceramics

- Strategic metals

- Salt

- Slaves

- Lumber

- Aroma compounds

- Spices

Subjects

- Commerce

- Architecture

- Watercraft

- Painting and Drawing

- Environment

- Conflict

- Faith

- Government

- Custom and Law

- Metallurgy