Southeast Asia (1252–1395 CE): Mongol Campaigns, Theravāda …

Years: 1252 - 1395

Southeast Asia (1252–1395 CE): Mongol Campaigns, Theravāda Ascendancy, and Maritime Gateways

Geographic and Environmental Framework

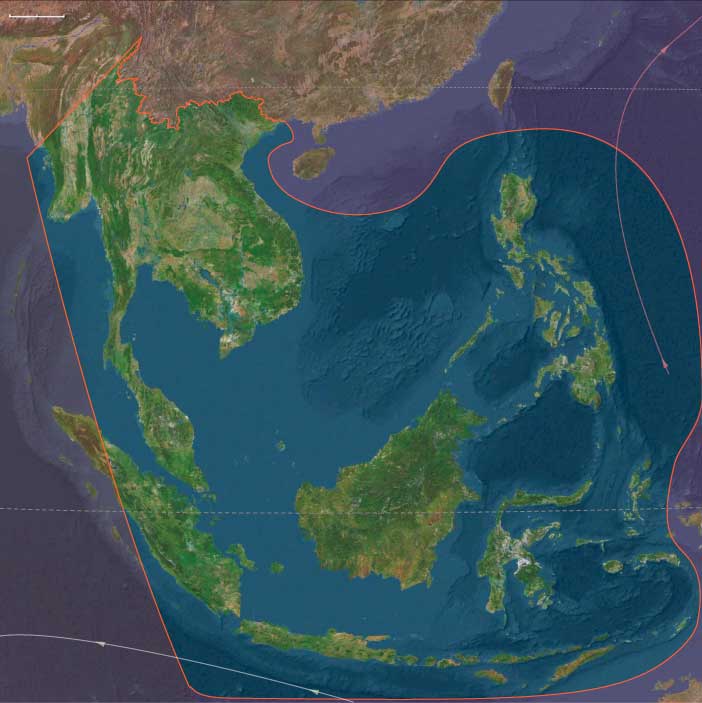

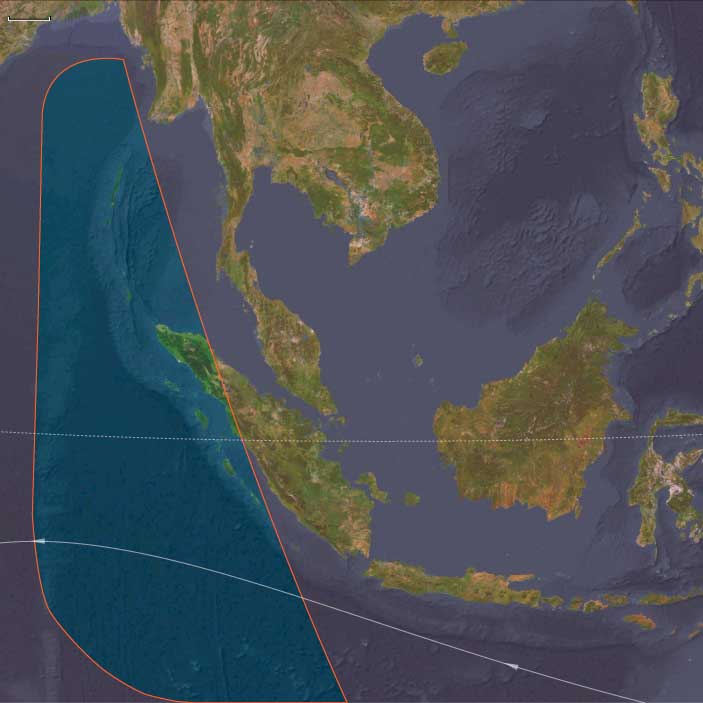

Southeast Asia in the Lower Late Medieval Age stretched from the river deltas of the Irrawaddy, Chao Phraya, Mekong, and Red Rivers to the volcanic archipelagos of Sumatra, Java, Borneo, and the Philippines, and westward to the island thresholds of Andamanasia—including Aceh, Nias, Mentawai, and the Andaman and Nicobar Islands.

The region bridged the Indian Ocean and the South China Sea, forming one of the world’s most vital crossroads for maritime trade and cultural exchange. Fertile deltas sustained dense agrarian civilizations; volcanic islands fostered powerful maritime states; and outer island arcs and forested archipelagos acted as buffer zones between great commercial worlds.

Climate and Environmental Shifts

The onset of the Little Ice Age (after c. 1300 CE) brought erratic monsoon cycles, alternating floods and droughts, and stronger typhoons across the western Pacific.

-

Mainland deltas mitigated risk through large-scale irrigation and reservoir systems.

-

Volcanic islands such as Java and Sumatra retained fertile soils; hydraulic engineering sustained stable yields.

-

Coastal and insular zones like Aceh, Vietnam, and the Philippines faced more frequent storms and crop losses.

-

Outer islands—Nias, Mentawai, and the Andamans—experienced tectonic and climatic volatility yet maintained ecological balance through mixed farming, fishing, and foraging.

Societies and Political Developments

Mainland Kingdoms

-

Pagan (Burma): Collapsed after the Mongol invasions (1277–1287 CE), giving rise to successor polities at Ava, Hanthawaddy, and in the Shan uplands.

-

Khmer Empire (Angkor): Reached its monumental zenith under Jayavarman VII but declined by the 14th century amid Thai incursions and internal stress.

-

Sukhothai and Ayutthaya (Thailand): Sukhothai, founded c. 1238, became a major Theravāda Buddhist center before absorption by Ayutthaya (founded 1351), which rose as a dominant power in the Chao Phraya basin.

-

Lan Xang (Laos): Formed in 1353 under Fa Ngum, establishing a durable Tai-Lao highland kingdom.

-

Vietnam: Under the Trần dynasty, Vietnam repelled three Mongol invasions (1257, 1284–85, 1287–88), securing independence from China and consolidating a Confucian–Buddhist administrative order.

Island Kingdoms and Maritime Polities

-

Majapahit Empire (Java): Founded in 1293 after expelling a Mongol expedition, Majapahit unified much of the Indonesian archipelago through alliances, tribute, and naval power. Its court chronicled regional supremacy in the Nagarakretagama (1365).

-

Sumatra: With Srivijaya’s decline, Malayu (Jambi) and Aceh competed for influence, drawing connections to both Majapahit and emerging Muslim trade networks.

-

Borneo, Sulawesi, and the Philippines: Hosted regional chiefdoms tied by trade in forest products, pearls, and gold.

-

Moluccas and Banda Islands: Served as the global source of cloves, nutmeg, and mace—commodities that drew Indian, Arab, and Chinese merchants.

-

Andamanasia: At the western fringe, Aceh rose as a Muslim harbor state controlling the Strait of Malacca, while surrounding islands such as Nias and Mentawai maintained independent megalithic and ancestor-based societies.

Economy and Exchange Networks

Agriculture and Production

-

Wet-rice cultivation dominated the mainland deltas (Chao Phraya, Mekong, Red River).

-

Terraced farming and irrigation supported Javanese and Khmer populations.

-

Cash crops: pepper, spices, camphor, sandalwood, and resins flowed to foreign markets.

-

Outer islands: swidden horticulture, sago and yam cultivation, and coconut groves balanced subsistence and trade.

-

Aceh’s plains produced rice and pepper, while the Andaman forests sustained sago, yams, and fruit.

Trade and Maritime Corridors

-

Indian Ocean–China Sea axis: The Straits of Malacca, Sunda, and the South China Sea functioned as arteries of global exchange.

-

Majapahit’s ports (Tuban, Gresik, Trowulan) controlled archipelagic routes.

-

Tumasik (Singapore) and Aceh prospered as pre-Melaka entrepôts.

-

Philippine polities exported gold, wax, and forest goods to China.

-

Spice routes: the Moluccas supplied cloves and nutmeg through Javanese merchants to India, Arabia, and beyond.

-

Inter-island trade: Simeulue, Nias, and Mentawai provided coconuts, forest goods, and captives to Sumatran ports; Andaman and Nicobar Islanders exchanged resin, coconuts, and forest products for metal and cloth.

The region’s maritime economy operated through monsoon-driven shipping, adapting to seasonal winds that carried Chinese junks, Arab dhows, and Malay vessels between oceans.

Subsistence, Technology, and Material Culture

-

Hydraulic engineering: Angkor’s barays (reservoirs), Pagan’s canals, and Javanese terrace systems underpinned stable agriculture.

-

Shipbuilding: Javanese jong—massive multi-masted ships—carried bulk cargoes across the Indian Ocean; smaller Malay and Cham vessels linked coastal ports.

-

Military innovations: elephants in mainland warfare; fire-rafts and boarding tactics in Javanese naval engagements.

-

Craft industries: Khmer stone sculpture, Javanese temple reliefs, Vietnamese ceramics, and fine batik textiles expressed sophisticated artistry.

-

Outer island crafts: Nias stone monuments, Mentawai carvings, and Andaman bows and canoes reflected local adaptation and identity.

Belief and Symbolism

Religious and philosophical systems intertwined from India, China, and the Pacific:

-

Theravāda Buddhism spread from Sri Lanka to Sukhothai, Lan Xang, and Ava, establishing monarchs as dhammaraja—righteous upholders of moral law.

-

Mahayana Buddhism and Hinduism persisted in Angkor and Java, merging into Hindu–Buddhist syncretism under Majapahit.

-

Vietnam combined Confucian bureaucracy with Buddhist and Taoist elements.

-

Islam entered northern Sumatra (Aceh, Pasai) through merchant networks and Sufi orders.

-

Outer island cosmologies: ancestor worship, spirit cults, and animist ritual persisted in Nias, Mentawai, and the Andamans, while Andamanese hunters honored forest and sea spirits through dance and taboo.

Across the region, syncretism served as a stabilizing force—uniting diverse communities under shared ritual and trade.

Adaptation and Resilience

-

Agricultural diversification—combining wet rice with upland crops and orchard species—buffered monsoon irregularities.

-

Maritime redundancy: When one harbor declined, others rose—Tumasik, Pasai, Tuban, or Ayutthaya.

-

Political reorganization: As Angkor and Pagan waned, Ayutthaya, Lan Xang, and Majapahit preserved continuity through renewed networks of faith and trade.

-

Syncretic religion eased cultural transition, integrating Hindu–Buddhist, Islamic, and local beliefs.

-

Island resilience: Swidden, arboriculture, and diversified fishing stabilized life on outer islands; stilted longhouses protected against floods and quakes.

Long-Term Significance

By 1395 CE, Southeast Asia was a region of remarkable dynamism and transformation:

-

Majapahit had forged the last great Hindu–Buddhist maritime empire, commanding tribute across the archipelago and dominating trade routes from the Sunda Strait to the South China Sea.

-

Ayutthaya and Lan Xang rose as the new centers of Theravāda statecraft, ensuring continuity on the mainland after Angkor’s decline.

-

Vietnam entrenched its independence and Confucian bureaucracy following its victories over the Mongols.

-

Aceh emerged as a nascent Islamic kingdom controlling the Malacca gateway, while outer island cultures—Nias, Mentawai, and the Andamans—retained deep ancestral traditions.

-

The spice islands and Malay ports kept the region tightly bound to Afro-Eurasian commerce, linking China, India, and Arabia through the predictable rhythm of the monsoon.

Southeast Asia thus stood at the threshold of a new era—its kingdoms resilient, its trade arteries vibrant, and its maritime and religious networks preparing to confront the global transformations of the coming centuries.

People

Groups

- Hinduism

- Mon people

- Khmer people

- Vietnamese people

- Tai peoples, or Thais

- Buddhism

- Buddhists, Theravada

- Cham people

- Malays, Ethnic

- Buddhism, Mahayana

- Kedah, Malay state of

- Srivijaya, Malay kingdom of

- Melayu Kingdom

- Champa, Kingdom of

- Khmer Empire (Angkor)

- Bamar or Burmans

- Mon Kingdoms

- Pagan (Bagan), Kingdom of

- Ngô dynasty

- Shan people

- Champa, Kingdom of

- Chola Empire

- Kediri, Kingdom of

- Dai Viet, Kingdom of

- Mongols

- Chinese Empire, Nan (Southern) Song Dynasty

- Mongol Empire

- Sukhothai (Siam), Thai state of

- Chinese Empire, Yüan, or Mongol, Dynasty

- Shan States

- Majapahit Empire

- Lanna, or Lan Na (Siam), Thai kingdom of

- Ayutthaya (Siam), Thai state of

- Lan Xang, Kingdom of

- Sukhothai (Siam), Thai vassal kingdom of

Topics

- Mongol Conquests

- Mongol invasions of Vietnam

- Mongol Invasion of Burma, or Mongol-Burmese War of 1277-87

- Little Ice Age, Warm Phase I

- Little Ice Age (LIA)

Commodoties

- Weapons

- Glass

- Oils, gums, resins, and waxes

- Grains and produce

- Textiles

- Ceramics

- Strategic metals

- Salt

- Slaves

- Lumber

- Aroma compounds

- Spices

Subjects

- Commerce

- Architecture

- Watercraft

- Painting and Drawing

- Environment

- Conflict

- Faith

- Government

- Custom and Law

- Metallurgy