Australasia (28,577 – 7,822 BCE): Late Pleistocene–Early …

Years: 28577BCE - 7822BCE

Australasia (28,577 – 7,822 BCE): Late Pleistocene–Early Holocene — From Glacial Plains to Island Worlds

Geographic & Environmental Context

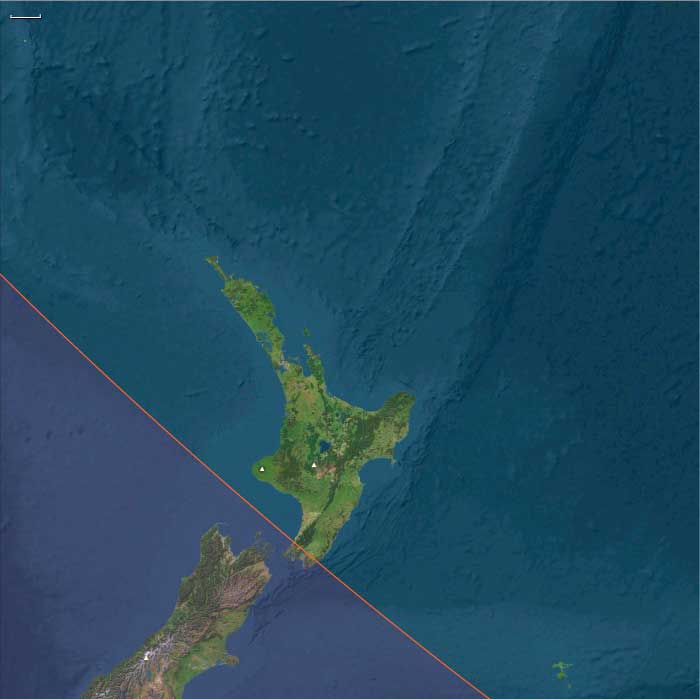

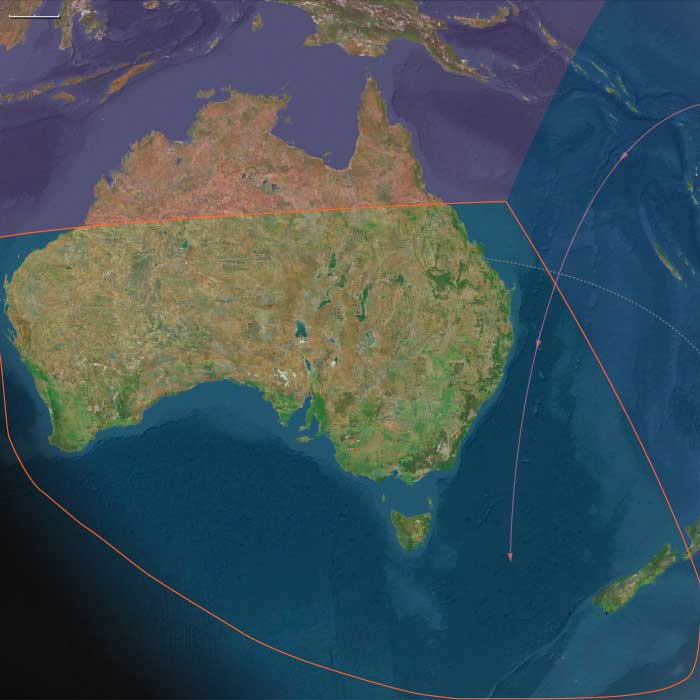

During the Late Pleistocene and early Holocene, Australasia—comprising the continental landmass of Sahul (Australia–New Guinea–Tasmania) and the surrounding islands of South Polynesia (Aotearoa North Island, the Chathams / Rēkohu, Norfolk, and the Kermadecs)—was a realm of sweeping change.

At the Last Glacial Maximum (c. 26,500 – 19,000 BCE), sea levels lay more than 100 m below present. Vast plains joined New Guinea to northern Australia across the Arafura and Carpentaria Seas, and Tasmania to the mainland via the Bassian Plain. As ice retreated, these land bridges drowned; coastlines advanced hundreds of kilometres inland; lagoons, gulfs, and barrier systems took their modern form.

By 7,800 BCE, Australia, Tasmania, and New Zealand had assumed their familiar outlines, while South Polynesia remained unpeopled but ecologically transformed by rising seas and forest renewal.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

The period opened with cold, dry glacial climates and closed in a warm, moist Holocene optimum:

-

Last Glacial Maximum: steppe and open woodland replaced most southern forests; glaciers advanced in the Southern Alps of New Zealand and the Tasmanian highlands; monsoons weakened across northern Australia.

-

Bølling–Allerød Interstadial (c. 14,700–12,900 BCE): abrupt warming strengthened rainfall; mangroves and freshwater wetlands spread along northern coasts; temperate forests began to return.

-

Younger Dryas (12,900–11,700 BCE): short-lived cooling and aridity contracted forests once more, forcing people and wildlife toward permanent water sources.

-

Early Holocene (after 11,700 BCE): temperatures rose rapidly; full-strength monsoons and westerlies re-established; rivers and lakes reached high stands; vegetation zones stabilized in patterns still recognizable today.

Subsistence & Settlement

Across Sahul, Aboriginal Australians maintained traditions of mobility and ecological engineering that stretched back tens of millennia, while the islands of South Polynesia remained uninhabited yet ecologically dynamic.

-

Northern Australia: monsoon cycles structured life. Wet-season dispersal exploited fish, turtles, waterfowl, and plant foods in flooded plains; dry-season concentration along coasts and permanent billabongs ensured continuity. Dugong, shellfish, and estuarine fish provided marine staples; yams, pandanus, and nuts formed key plant foods.

-

Southern Australia & Tasmania: people ranged between inland plains and coasts, taking kangaroos, wallabies, emus, seals, shellfish, and estuarine fish. In winter, Tasmanians depended heavily on marine mammals and shellfish when plant foods were scarce.

-

South Polynesia (Aotearoa North Island / Chathams / Norfolk / Kermadecs): still without humans, forests of podocarp–kauri–beech recolonized valleys and slopes; wetlands developed behind new barrier systems; seabird colonies fertilized emerging dunes and rocky headlands.

Settlement systems in Sahul were seasonally mobile but geographically stable—the same river bends, dune ridges, and coastal coves revisited across generations.

Technology & Material Culture

Toolkits throughout Australasia reflected continuity and regional innovation:

-

Ground-edge axes, adzes, and microlithic inserts formed multipurpose tool systems for woodworking and hunting.

-

Grinding stones processed seeds and tubers; nets, traps, and fish spears targeted aquatic resources.

-

Bark canoes and rafts enabled near-shore travel and river crossings.

-

Ochre served in art, ceremony, and body decoration.

In unpeopled South Polynesia, volcanic processes and sea-level change remained the sole “technologies,” carving gulfs, reefs, and estuaries that would one day host Polynesian settlements.

Movement & Interaction Corridors

Mobility was both ecological and social:

-

In Sahul, the Murray–Darling, Fitzroy, Victoria, and Daly rivers acted as conduits linking inland hunting grounds with coastal and estuarine fisheries.

-

During lowered sea level, the Arafura Plain connected northern Australia to New Guinea, supporting cultural and genetic exchange.

-

With post-glacial flooding, canoe and raft routes replaced terrestrial corridors, knitting new coasts into maritime landscapes.

-

In the south, the Bassian Plain allowed interchange between mainland and Tasmania until its final submergence around 11,000 BCE.

-

South Polynesia’s Kermadec–Norfolk–Chatham chain, though unpeopled, formed emerging ecological stepping-stones across the southwest Pacific.

Cultural & Symbolic Expressions

Late-Pleistocene peoples of Sahul articulated deep symbolic landscapes:

-

Rock art flourished from the Kimberley to Tasmania, depicting animals, human figures, geometric motifs, and ancestral beings—the Dreaming etched in pigment.

-

Ceremonial gatherings marked resource peaks such as fish migrations or plant harvests, renewing kin alliances and ecological law.

-

Fire-stick farming and ritual burning were not merely utilitarian but cosmological acts that maintained balance between people, plants, and animals.

In contrast, the islands of South Polynesia were silent sanctuaries of natural succession, untouched by human story yet already inscribing their own ecological mythos in reef, forest, and wind.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

Resilience derived from mobility, ecological mapping, and knowledge transmission:

-

Controlled fire maintained open hunting grounds and promoted edible plant regrowth.

-

Seasonal calendars tied to rainfall, flowering, and animal movement guided travel and harvest.

-

Dietary diversity—from marine to inland plant resources—buffered climatic stress.

-

In the unpeopled islands to the east, fog interception, seabird fertilization, and forest regeneration created self-sustaining ecosystems that paralleled human adaptive strategies elsewhere.

Long-Term Significance

By 7,822 BCE, Australasia had entered the Holocene as a transformed but continuous world:

-

Northern Australia enjoyed full monsoonal vigor and thriving estuaries;

-

Southern Australia and Tasmania adapted seamlessly to post-glacial coasts;

-

Sahul’s unity dissolved as rising seas isolated New Guinea and Tasmania, inaugurating new regional cultures;

-

South Polynesia, still without people, stood ecologically ready—its forests, wetlands, and lagoons stabilized in the forms that would greet the first Polynesian navigators tens of millennia later.

This epoch fixed the environmental foundations of the southern hemisphere’s enduring societies and landscapes—ancient continuity beneath a changing sea.