South Polynesia (1684–1827 CE): Māori Intensification, Moriori …

Years: 1684 - 1827

South Polynesia (1684–1827 CE): Māori Intensification, Moriori Resilience, and Early European Intrusions

Geography & Environmental Context

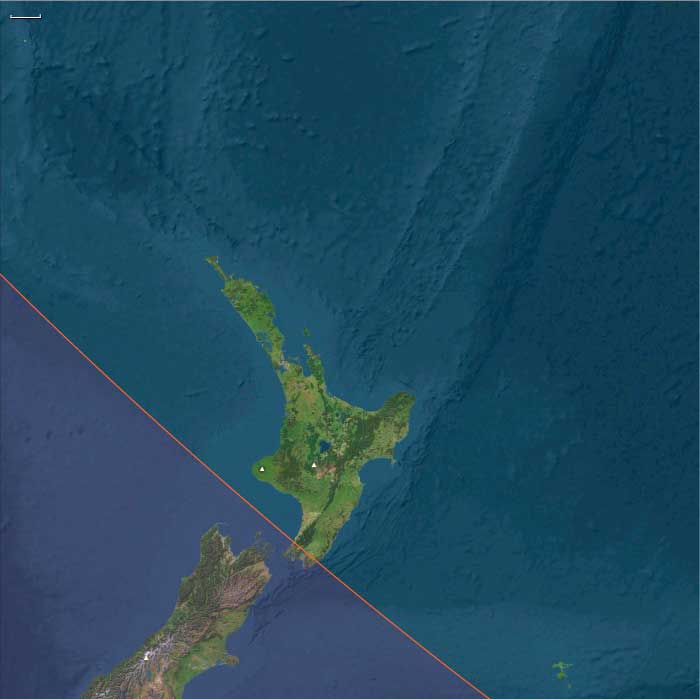

South Polynesia includes New Zealand’s North Island (except its southwestern tip), the Chatham Islands, Norfolk Island, and the Kermadec Islands. Anchors include the Waikato basin, the Bay of Islands, the volcanic spine of the Central Plateau (Tongariro, Taupō, Taranaki), the Northland peninsulas, the Chatham Islands’ cool oceanic plains, Norfolk’s basalt soils and pines, and the volcanic Kermadecs. The subregion spans temperate to subtropical zones, supporting horticulture, rich fisheries, and diverse coastal ecologies.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

The North Island enjoyed reliable rainfall, though droughts periodically afflicted its east coast. Volcanic activity persisted (e.g., Tongariro and White Island eruptions). The Chatham Islands, further east, had cooler, wetter conditions, limiting kūmara cultivation. Norfolk and the Kermadecs were uninhabited but noted by passing Polynesian voyagers and later Europeans. Storms and occasional cyclones swept the coasts, shaping settlement patterns and resource use.

Subsistence & Settlement

-

Māori (North Island): Cultivated kūmara, taro, yams, and gourds; fern root and forest birds supplemented diets. Fishing and shellfish gathering were central. Fortified pā (hilltop strongholds) anchored communities, and large waka (canoes) enabled transport and warfare.

-

Moriori (Chathams): Practiced marine-based subsistence—fishing, birding, root crops, and foraging—with a pacifist ethos that emphasized nonviolence and resource balance.

-

Norfolk & Kermadecs: Uninhabited in this era, but Norfolk’s fertile land and towering pines attracted later European interest; the Kermadecs served as occasional stopovers for voyagers and whalers.

Technology & Material Culture

-

Māori technologies: Double-hulled canoes (waka hourua), intricate wood carving, flax weaving, stone adzes, and greenstone (pounamu) tools and weapons. By the early 19th century, muskets, iron, and European textiles entered Māori material culture.

-

Moriori lifeways: Light canoes adapted to the Chathams’ conditions; plaited mats, wood tools, and fishhooks reflected maritime adaptation.

-

Introductions: European iron nails, axes, and muskets—obtained through trade with whalers and sealers—reshaped Māori society, especially warfare.

Movement & Interaction Corridors

-

Polynesian networks: Inter-iwi exchange flourished across the North Island, while Māori voyagers interacted with the Chathams.

-

European arrival: Abel Tasman (1642) and James Cook (1769) mapped coasts; from the late 18th century, sealers, whalers, and traders frequented the Bay of Islands and Hauraki Gulf.

-

Missionary stations: From 1814, the London Missionary Society established missions in the Bay of Islands, spreading Christianity, literacy, and new crops.

-

Trade: Māori exchanged timber, flax, pork, and food for muskets, iron tools, and cloth.

Cultural & Symbolic Expressions

-

Māori society: Structured by kin groups (iwi, hapū), prestige (mana), and ancestral authority (tapu). Carved meeting houses, oral whakapapa (genealogies), and oratory in marae embodied identity.

-

Moriori ethos: Centered on peace and environmental balance, with communal rituals and oral traditions preserving identity.

-

European influences: Christian teachings and literacy began to take hold, though Māori selectively incorporated them into existing frameworks.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

-

Māori: Terracing, kūmara storage pits, and careful microclimate selection expanded horticulture’s reach. Coastal and riverine fisheries buffered against crop failures.

-

Moriori: Relied on fishing and birding to adapt to the Chathams’ cooler climate.

-

Cultural resilience: Kinship and reciprocity stabilized food sharing; oral traditions reinforced stewardship of land and sea.

Political & Military Shocks

-

Māori intertribal conflict: Warfare was endemic but intensified dramatically after the introduction of muskets in the early 19th century, sparking the “Musket Wars” and mass displacements.

-

European incursions: Cook’s voyages (1769–77) opened sustained European contact; whalers and sealers established shore stations, often disrupting local ecologies.

-

Missionaries: Introduced new belief systems and literacy, reshaping cultural landscapes.

-

Norfolk & Kermadecs: Observed by European navigators as potential bases but not yet colonized.

Transition

Between 1684 and 1827, South Polynesia was a dynamic world of Māori horticultural intensification, Moriori maritime resilience, and mounting European contact. The Bay of Islands became a hub of trade and cultural exchange, missions introduced Christianity and literacy, and muskets revolutionized Māori conflict. Norfolk and the Kermadecs remained marginal but strategically noted by explorers. By 1827, the region stood on the threshold of colonization, with Indigenous societies resilient yet deeply altered by global trade, warfare, and missionary influence.

People

Groups

- Aotearoa

- Moriori people

- Maori people

- France, (Bourbon) Kingdom of

- Britain (United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland)

- Netherlands, Kingdom of The United

Topics

Commodoties

Subjects

- Commerce

- Watercraft

- Environment

- Public health

- Conflict

- Exploration

- Government

- Custom and Law

- Catastrophe

- Human Migration