South America (1684–1827 CE) Imperial Reforms, …

Years: 1684 - 1827

South America (1684–1827 CE)

Imperial Reforms, Indigenous Resistance, and the Wars of Independence

Geographic Definition of South America

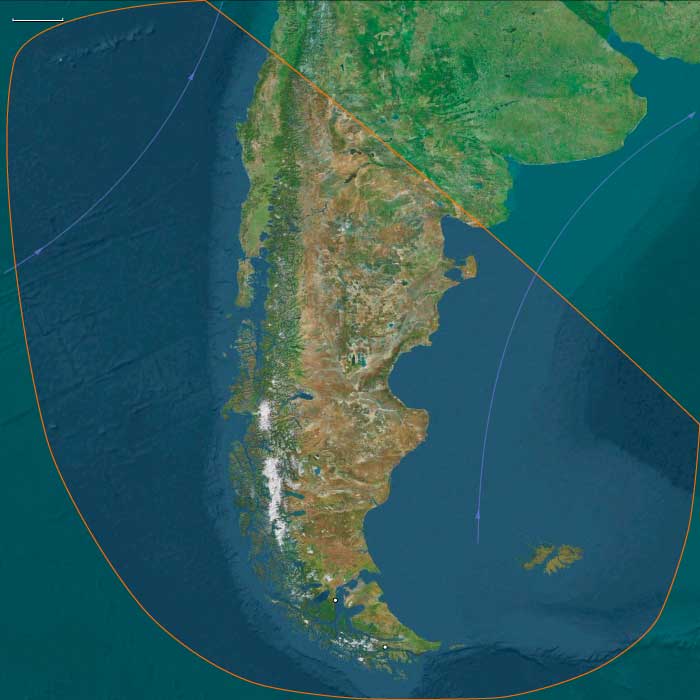

The region of South America encompasses all lands south of the Isthmus of Panama, including South America Major—stretching from Colombia and Venezuela through Brazil, Peru, Bolivia, Paraguay, Uruguay, northern Argentina, and northern Chile—and Peninsular South America, embracing southern Chile and Argentina, Patagonia, Tierra del Fuego, the Falkland Islands (Islas Malvinas), and the Juan Fernández Islands.

Anchors include the Andes cordillera and Altiplano, the Amazon, Orinoco, and Magdalena river systems, the Venezuelan Llanos, Gran Chaco, Pampas, and Patagonian steppe, extending southward to the Strait of Magellan and the storm-lashed sub-Antarctic islands.

Bounded by Isthmian America to the north and Subcontinental South America beyond the Río Negro, this region entered the modern age as a vast, fragmented world of empires, Indigenous sovereignties, and the first stirrings of republican independence.

Geography and Imperial Frontiers

Between 1684 and 1827, South America stood at the hinge of early modern empire and emerging nationhood. The Andes anchored Spanish dominion, while the Amazon, Guianas, and southern plains remained zones of relative autonomy.

Spain’s empire centered on Lima, Potosí, and Bogotá, but new routes and rival powers eroded its control. Portuguese settlers pushed westward beyond the Treaty of Tordesillas, carving the future Brazil from mining frontiers and sugar coasts. The Guianas hosted Dutch, French, and British enclaves; the Llanos, Chaco, and Patagonia remained largely Indigenous.

From the Bio-Bío frontier in Chile to the Missions of Paraguay and the Upper Amazon, Indigenous confederations, Jesuit enclaves, and frontier forts coexisted in uneasy equilibrium until the revolutions of the early nineteenth century broke the imperial map apart.

Climate and Environmental Shifts

The late Little Ice Age lingered into the eighteenth century:

-

Andean highlands: Frosts shortened growing seasons; glacial advance cut water supply to terraces.

-

Amazon basin: Rainfall fluctuated with El Niño and La Niña, alternately flooding and parching river villages.

-

Coastal Peru and Chile: El Niño upsets brought famine and fishery collapse.

-

Southern pampas and Patagonia: Droughts and winds intensified; cold decades preserved glaciers in Tierra del Fuego.

Despite these oscillations, Indigenous and colonial agrarian systems—terraces, irrigation, and mixed cropping—sustained resilience across climates.

Subsistence and Settlement

Colonial economies deepened even as empires strained to contain their frontiers:

-

Andean viceroyalties (Peru, Bolivia, Ecuador): Silver and mercury mining at Potosí, Oruro, and Huancavelica remained imperial lifelines; Indigenous mita labor persisted under new guises. Highland farmers supplied maize, potatoes, and quinoa to mining centers.

-

Brazil: Gold and diamond booms in Minas Gerais and Goiás (1690s onward) drew settlers inland. Sugar, cattle, and later coffee expanded in Bahia, Pernambuco, and the Recôncavo.

-

Paraguay and Uruguay: Yerba mate, hides, and cattle exports linked Jesuit missions and ranches to Atlantic trade.

-

Venezuela and Colombia: The Llanos produced cattle and cocoa; Caracas, Cartagena, and Bogotá tied the interior to Europe via Caribbean ports.

-

Chile and the Río de la Plata: Wheat and wine sustained the Pacific colonies; Buenos Aires rose as a smuggling and trade hub after its 1776 elevation to viceroyal capital.

-

Southern frontiers: Beyond the Bio-Bío, the Mapuche retained independence; Tehuelche horsemen roamed Patagonia; Fuegian canoe peoples survived at the edge of the sub-Antarctic seas.

Urban centers—Lima, Quito, La Paz, Buenos Aires, Rio de Janeiro, Salvador, Caracas, Bogotá, and Santiago—flourished as administrative, mercantile, and religious capitals binding the continent’s diverse ecologies into imperial networks.

Technology and Material Culture

Colonial material life fused Indigenous skill and European design.

Roads and mule trails replaced Inca highways; stone and adobe churches rose over older shrines. Mining technologies—waterwheels, furnaces, mercury amalgamation—refined Andean ores. Jesuit reductions in Paraguay and Boliviaproduced Baroque churches, carved imagery, and polyphonic music blending European instruments with Guaraní voices.

In southern Chile and Patagonia, horse and iron tools transformed Indigenous mobility and warfare, while Spanish ports outfitted galleons and whalers bound for the Strait of Magellan.

Movement and Interaction Corridors

The continent’s arteries of exchange intertwined:

-

Silver highways: Carried bullion from Potosí to Lima and Buenos Aires, then to Seville.

-

Amazonian rivers: Sustained mission networks and trade in cacao, dyes, and forest goods.

-

Jesuit routes: Linked the Guaraní reductions to coastal Brazil and Peru until their 1767 suppression.

-

Slave routes: Africans entered through Cartagena, Bahia, and Rio de Janeiro, infusing the Atlantic littoral with Afro-American cultures.

-

Frontier circuits: Horses, cattle, and textiles moved between the Llanos, Chaco, Araucanía, and Pampas, blurring boundaries between empire and autonomy.

-

Southern seas: The Falklands and Juan Fernández Islands became whaling and provisioning hubs; the Strait of Magellan gained strategic significance for global shipping.

Cultural and Symbolic Expressions

Baroque Catholicism shaped public life—cathedrals, processions, and festivals dominated cities—yet beneath its veneer Indigenous and African traditions thrived.

In the Andes, saints merged with huacas and mountain spirits; in Brazil, candomblé and capoeira fused faith and resistance; in the missions, music and sculpture translated theology into local idioms.

Creole intellectuals absorbed Enlightenment ideas: scholars such as Juan Pablo Viscardo y Guzmán, Francisco de Miranda, and Simón Rodríguez envisioned liberty and reform. Across the south, Mapuche ngillatun and Tehuelche rituals reaffirmed identity against colonial advance, while sailors and exiles endowed remote islands with myths of endurance—from the Jesuit martyrdoms of Chiloé to Selkirk’s solitude on Juan Fernández.

Environmental Adaptation and Resilience

Agricultural and ecological ingenuity persisted:

terraced farming, irrigation canals, and crop diversity buffered Andean villages; shifting cultivation and forest gardens stabilized Amazonian societies.

Pastoralism spread—cattle on the Pampas, sheep on Patagonian plains—reshaping grasslands and displacing wildlife.

Indigenous nations south of the Andes adapted the horse, expanding mobility and defense. Coastal communities recovered from earthquakes and volcanic eruptions, rebuilding cities with brick, tile, and lime.

Technology and Power Shifts (Conflict Dynamics)

By the eighteenth century, reform and resistance accelerated collapse of the old order:

-

Bourbon Reforms (Spain) and Pombaline Reforms (Portugal) sought efficiency and revenue, tightening imperial control but provoking resentment.

-

Jesuit Expulsion (1759–1767): Dismantled mission economies and destabilized Indigenous frontiers.

-

Indigenous revolts: The Comunero uprisings (New Granada, 1781) and Túpac Amaru II’s Rebellion (Peru, 1780–81) fused anti-tax protest with ancestral revival.

-

Slave and maroon resistance: Palmares in Brazil and quilombos across the Guianas and Venezuela embodied enduring defiance.

-

Wars of Independence (1810–1824): From the Caracas junta to the crossing of the Andes, revolution swept the continent. Leaders—Simón Bolívar, José de San Martín, Bernardo O’Higgins, and José Artigas—toppled viceroyalties and declared new republics.

In the south, Chile’s patriots triumphed after Chacabuco (1817) and Maipú (1818); Argentina secured independence under the United Provinces; Brazil separated peacefully from Portugal in 1822 under Dom Pedro I. Yet Indigenous nations in Patagonia and Araucanía, though weakened, remained outside firm national control until late in the following century.

Transition (to 1827 CE)

By 1827 CE, the map of South America was redrawn. The viceroyalties of Spain and the captaincy of Portugal had dissolved into a dozen republics and one empire.

Lima, Buenos Aires, Bogotá, Caracas, and Rio de Janeiro emerged as capitals of sovereign states.

The Mapuche, Tehuelche, and Fuegians still held the far south; the Falklands and Juan Fernández Islands became contested imperial outposts.

Mining and plantation economies endured but shifted under new flags, while slavery, tribute, and caste hierarchies began to crumble.

The colonial age had ended: South America entered the modern era forged in rebellion, grounded in geography, and alive with the intertwined legacies of empire, Indigenous endurance, and creole revolution.

People

- Antonio José de Sucre

- José Gaspar Rodríguez de Francia

- José Gervasio Artigas

- José de San Martín

- Pedro I of Brazil

- Simón Bolívar

- Túpac Amaru II

Groups

- Mapuche (Amerind tribe)

- Guaraní (Amerind tribe)

- Christians, Roman Catholic

- Portuguese Empire

- Inca Empire

- Spanish Empire

- Spaniards (Latins)

- Jesuits, or Order of the Society of Jesus

- Chile (Spanish colony)

- Peru, Viceroyalty of

- Venezuela Province

- Spain, Bourbon Kingdom of

- Venezuela, Captaincy General of

- Chile, Republic of

- Paraguay, Republic of

- Venezuela, Second Republic of

- Colombia, Republic of (Gran Colombia)

- Peru, Republic of

- Bolivia, Republic of

Topics

- Age of Discovery

- Atlantic slave trade

- Colonization of the Americas, Portuguese

- Colonization of the Americas, Spanish

- Jesuits, Political Suppression of the

- Jesuits, Papal Suppression of the

- French Revolution

- Haitian Revolution

- Argentine War of Independence

- Spanish American wars of independence

- Chilean War of Independence

- Colombian War of Independence

- Argentine War of Independence

- Paraguayan War of Independence

- Chilean Revolt

- Bolivar's War

- Venezuelan War of Independence

- Bolivar in Venezuela

- Boyacá, Battle of

- Carabobo, Battle of

- Junín, Battle of

- Ayacucho, Battle of