South America (1396–1539 CE) Andean Empires, …

Years: 1396 - 1539

South America (1396–1539 CE)

Andean Empires, Forest Realms, and Southern Frontiers

Geographic Definition of South America

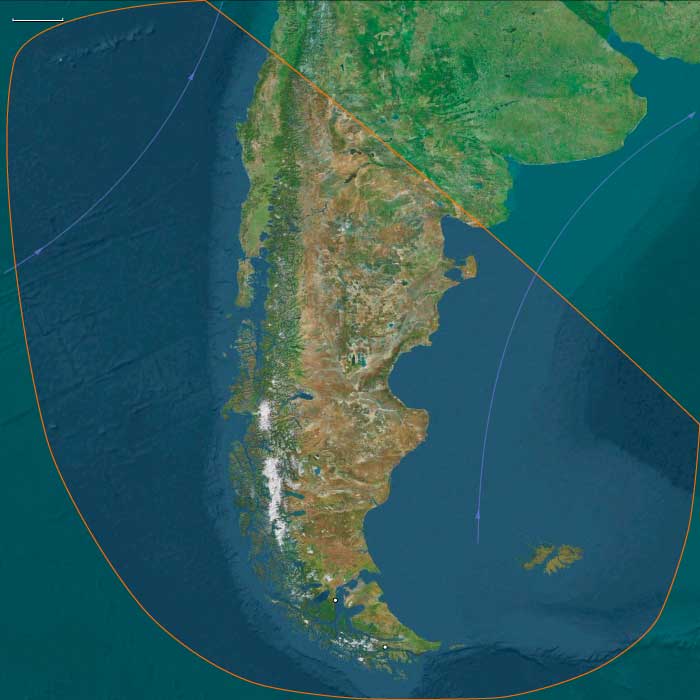

The region of South America includes all lands south of the Isthmus of Panama and comprises two subregions: South America Major—the entire continental span north of the Río Negro (Brazil, Uruguay, Paraguay, northern Argentina and northern Chile, Bolivia, Peru, Ecuador (excluding the Cape lands at the Isthmian boundary), Colombia (excluding the Darién), Venezuela, Guyana, Suriname, French Guiana)—and Peninsular South America, embracing southern Chile (including the Central Valley), southern Argentina (Patagonia south of the Río Negro and Río Grande), Tierra del Fuego, the Falkland Islands (Islas Malvinas), and the Juan Fernández Islands.

Anchors include the Andes cordillera and Altiplano, the Amazon basin, the Orinoco and Magdalena river systems, the Venezuelan Llanos, the Gran Chaco, the Uruguayan Pampas, the Guiana Shield, the Araucanian Andes, and the Strait of Magellan. Bounded by Isthmian America to the north and Subcontinental South America beyond the Río Negro, these ecologies linked Pacific highlands and Atlantic forests through riverine highways and mountain roads long before Europeans arrived.

Geography & Environmental Framework

The early Little Ice Age sharpened climatic contrasts across the continent.

In the Andes, cooler temperatures and episodic frosts shortened growing seasons on the Altiplano, while recurring El Niño cycles brought destructive floods and fishery collapses to the Pacific littoral. The Amazon and Orinoco basins alternated between decades of deluge and drought; the Gran Chaco swung between swollen floodplains and aridity; the Llanos and Pampas pulsed with seasonal waters. Far to the south, Patagonia and Tierra del Fuego grew colder and stormier, glaciers pressing into fjords while the Central Valley of Chile cycled through droughts and floods.

Despite these stresses, Indigenous systems—terraces and canals, terra preta gardens, floodplain fields, and mobile hunting grounds—sustained abundant populations from mountain to coast, forest to steppe.

Societies and Subsistence

Andean Empires and Highland Networks

The Inca Empire (Tawantinsuyu) reached its zenith in the fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries, uniting four administrative quarters from Quito to near Santiago around Cuzco. The imperial road, the Qhapaq Ñan, spanned over 30,000 kilometers, binding highlands to coastal valleys. Terraces, canals, and state storehouses (qollqas) supported maize, potato, quinoa, and coca across altitude zones; herds of llamas and alpacas supplied transport, fiber, and meat. Subordinate Aymara and Quechua polities—Lupaqa, Qulla, and others—kept local institutions within Inca oversight. Along the arid Pacific coast, irrigated valleys sustained dense populations; fishing communities harvested anchovy and shellfish, trading dried fish and salt to the highlands.

Lowland and Forest Civilizations

Beyond the Andes, tropical lowlands sustained intricate worlds of their own.

In the Amazon, Arawak, Tupí, and other language families cultivated manioc, maize, and beans in rotational fields, including anthropogenic terra preta soils enriched by charcoal and compost. Large villages, causeways, and canals attested to regional density; fishing, hunting, and foraging diversified diets. On the Guiana Shield, palm-thatched longhouses, hammocks, refined pottery, and featherwork marked vibrant material cultures. Along the Orinoco and Llanos, semi-nomadic horticulturalists balanced floodplain fields with canoe-borne trade. In the Gran Chaco and Uruguay–Paraguay riverlands, Guaraní and Charrúa societies combined horticulture, fishing, and hunting, forming riverine alliances.

Northern Andes and Caribbean Rim

In Colombia, chiefdoms such as the Muisca organized salt, emerald, and gold economies across the Bogotá highlands; paved roads linked maize and tuber fields to market towns. Quimbaya goldsmiths and Tairona builders in the Caribbean Sierra Nevada produced exquisite metallurgy and stone architecture, connecting mountain terraces to coastal fisheries.

Southern Frontiers of the Peninsula

South of the Bio-Bío, Mapuche communities cultivated maize, beans, and potatoes in dispersed lof kin groups, defending autonomy through fortified palisades and seasonal war bands. Across the Patagonian steppe, Tehuelchehunters ranged after guanaco and rhea with bows and bolas. In Tierra del Fuego, Yaghan and Kawésqar peoples sustained canoe-borne seal and shellfish economies, while inland Selk’nam hunters conducted communal hain initiations. The Falklands and Juan Fernández remained uninhabited refuges for seabirds and marine mammals.

Technology & Material Culture

Andean engineering and lowland ingenuity framed a continent-wide repertoire.

The Inca perfected cyclopean stone walls—Sacsayhuamán—and terraced sanctuaries—Machu Picchu—while rope suspension bridges spanned abysses; quipu knotted cords recorded tribute and census. Bronze, silver, and gold alloys formed tools and ritual vessels; alpaca and vicuña textiles indicated rank.

In forests and riverlands, dugout canoes, blowguns, polished stone adzes, and woven baskets underpinned daily life. Amazonian and Orinoco ceramics bore incised geometry and red slips; featherwork and body paint expressed cosmology. Among the Guaraní, woodcarving and music—flutes, rattles, chanted epics—reinforced communal identity. In the south, Mapuche weavers, Tehuelche leatherworkers, and Fuegian canoe-builders adapted craft to wind, ice, and grassland.

Movement & Interaction Corridors

Trade and communication linked coast, mountain, and forest in a continental web.

The Qhapaq Ñan moved armies, officials, and goods between Cuzco, Quito, and Lake Titicaca, tying highlands to coastal ports. Amazonian rivers carried pottery, salt, and smoked fish between forest polities; the Orinoco and Magdalena connected interior chiefdoms to Caribbean outlets. Guaraní and Tupí routes along the Paraná and Paraguay rivers joined Atlantic forests to Andean foothills. Southern trails crossed Araucanía and Patagonia, while canoe channels threaded Tierra del Fuego’s archipelagos.

After 1492, Atlantic and Pacific intrusions intersected these networks: Vicente Yáñez Pinzón reached the Amazon (1500); Pedro Álvares Cabral made landfall in Brazil (1500); Francisco Pizarro advanced into Peru by 1532, capturing Atahualpa at Cajamarca—events that foreshadowed a continental upheaval.

Cultural & Symbolic Expressions

Andean cosmology integrated empire and environment.

Inti (Sun), Viracocha (creator), and mountain spirits (apus) governed a universe of reciprocity; ritual labor (mit’a), feasts, and offerings upheld cosmic balance. Temples such as Qorikancha and shrines on snow peaks fused state and sacred.

In the forests, shamanic traditions flourished: visionary ceremonies with ayahuasca mediated ancestral spirits and healing. Guaraní mythic songs evoked Yvy Marane’ỹ—the “Land Without Evil”—guiding communal migrations and ethical life. In the south, Mapuche ritual (ngillatun) honored ngen spirits of place; Selk’nam hain initiations dramatized the ordering myths of kin and cosmos. Across the continent, art, chant, and ceremony merged ecology and law.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

Resilience lay in diversity and exchange.

Highland terraces, irrigation, and crop staggering cushioned frost; qollqa storehouses preserved grain for redistribution. Lowland shifting cultivation maintained soil fertility; terra preta fields proved regenerative. Guaraní and Charrúa mobility balanced fishing, farming, and hunting along river corridors. Southern canoe nomads and steppe hunters redistributed risk through seasonal movement and alliance. Ritual specialists interpreted droughts, floods, and quakes within sacred narratives that stabilized society in crisis.

Technology & Power Shifts (Conflict Dynamics)

By the early sixteenth century, European voyages redrew boundaries.

Portugal’s claim to Brazil under Tordesillas (1494) opened Atlantic coasts to sugar and enslaved labor, while Spain’s Andean campaigns dismantled Inca sovereignty. Epidemics—smallpox, measles, influenza—moved faster than armies, fracturing polities from Cuzco to Caracas and along the Caribbean rim. Yet resistance flared in highlands, forests, and southern plains: local leaders preserved languages, rituals, and communal lands beneath the first colonial impositions.

Transition (to 1540 CE)

By 1539 CE, South America stood on the threshold of the colonial age.

In the Andes, imperial roads and storehouses were being repurposed by Spain; along Brazil’s shores, Portuguese footholds took root. The Amazon, Orinoco, Guianas, and southern fjords still pulsed with autonomous Indigenous life, though disease and slave raiding had begun to spread inland.

From Altiplano terraces to blackwater channels, from lof fields to Fuegian hearths, this was a continent of breathtaking resilience—empires, chiefdoms, and forest–fjord communities alike sustained by ancient ecological knowledge. The next age would bring conquest, conversion, and coerced labor on a continental scale—the end of one world and the turbulent birth of another.