South America (1828–1971 CE) Republics, Frontiers, …

Years: 1828 - 1971

South America (1828–1971 CE)

Republics, Frontiers, and the Modern Continent

Geographic Definition of South America

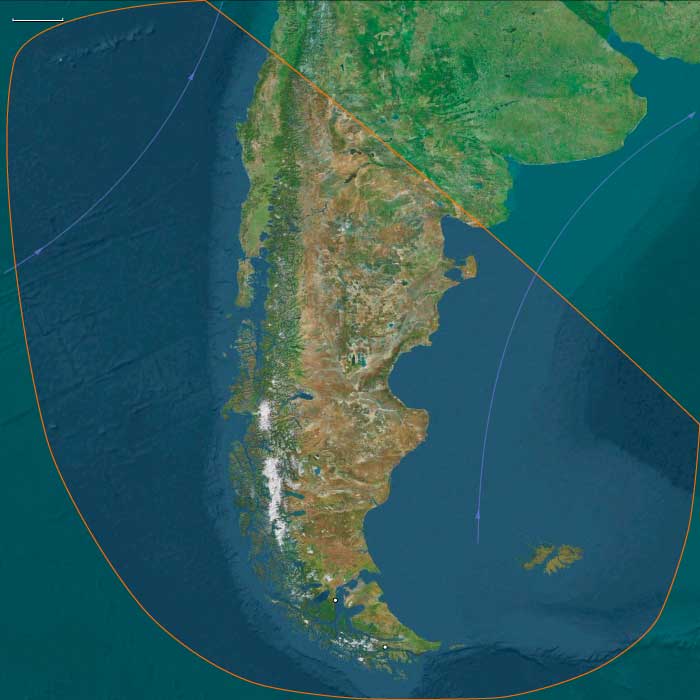

The region of South America encompasses all lands south of the Isthmus of Panama, including the subregions of South America Major—stretching from Colombia and Venezuela through Brazil, Bolivia, Peru, Ecuador, Paraguay, Uruguay, and northern Argentina and Chile—and Peninsular South America, which includes southern Chile, southern Argentina, Patagonia, Tierra del Fuego, the Falkland Islands (Islas Malvinas), and the Juan Fernández Islands.

Anchors include the Andes cordillera, the Altiplano, the Amazon, Orinoco, and Magdalena river systems, the Gran Chaco, the Llanos, the Pampas, and the Patagonian steppe, reaching south to the Strait of Magellan and the sub-Antarctic seas. This continental expanse unites rainforest and desert, mountain and plain, forming the world’s largest tropical forest system and one of its most diverse temperate frontiers.

Geography and Political Frontiers

Between 1828 and 1971, South America completed its transition from colonial empires to a constellation of modern nation-states. The nineteenth century was an age of consolidation—of borders, capitals, and frontiers—while the twentieth introduced urbanization, industrialization, and social revolution.

In the north and center, the Andes and Amazon defined the heartlands of South America Major: Brazil’s vast interior was opened by coffee, railways, and later industry; Peru, Bolivia, and Chile struggled over mineral frontiers; and the River Plate republics forged new economies on cattle and grain.

Farther south, Peninsular South America—Patagonia, Tierra del Fuego, and the southern islands—shifted from Indigenous autonomy to national incorporation under Chile, Argentina, and Britain. The conquest of Indigenous lands completed the continental frame of modern South America.

Climate and Environmental Shifts

With the close of the Little Ice Age, climate gradually warmed, though variability remained pronounced.

-

Andes: Glacial retreat altered water regimes; earthquakes and volcanic eruptions repeatedly struck Chile and Peru.

-

Amazon basin: Rainfall oscillated between flood and drought decades; deforestation and frontier ranching began to modify hydrology by the mid-twentieth century.

-

Llanos, Chaco, and Pampas: Drought and locust plagues punctuated otherwise fertile cycles; agriculture expanded through mechanization.

-

Patagonia and southern Chile: Winds remained fierce but temperatures moderated, fostering European colonization and ranching.

Environmental transformation followed human frontiers: new roads, plantations, and mines redrew both ecology and economy.

Subsistence and Settlement

Agrarian foundations persisted even as industry grew.

-

Andean republics: Highland farmers maintained terraced maize and potato fields; haciendas, mines, and plantations supplied global markets with silver, tin, and copper.

-

Brazil: Coffee, sugar, and later industrial production in São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro powered national growth; Amazon rubber boomed and collapsed; steel and oil replaced gold.

-

River Plate region: Argentina and Uruguay exported beef, wool, and grain, their estancias mechanized by the early twentieth century. Paraguay remained agrarian after its devastation in the War of the Triple Alliance (1864–1870).

-

Northern Andes and Caribbean coasts: Cocoa, coffee, and oil wealth transformed Venezuela and Colombia; pipelines and ports knit the mountains to the sea.

-

Southern Chile and Argentina: Wheat, forestry, and later nitrate and copper mining followed Indigenous dispossession; sheep ranching dominated Patagonia; Tierra del Fuego mixed gold rushes and estancias.

-

Falklands and Juan Fernández: Remote yet strategic, they sustained small ranching and fishing communities within imperial or national frameworks.

Urbanization intensified: Buenos Aires, São Paulo, Lima, Santiago, Bogotá, Caracas, and Montevideo became centers of power, drawing millions from countryside and abroad.

Technology and Material Culture

Railways, telegraphs, and steamships linked interior basins to coastal ports.

By the 1880s, rail lines climbed the Andes and spanned pampas and deserts; river steamers plied the Amazon, Orinoco, and Paraná–Paraguay. Telegraphs and later telephones connected capitals; radio and cinema shaped modern culture.

Architecture mirrored aspiration: neoclassical capitols, baroque cathedrals, and art-nouveau theaters proclaimed republican modernity. Industrialization—from Chilean copper smelters to Brazilian steel mills—transformed material life. Yet regional craft traditions endured: Andean textiles, Afro-Brazilian percussion, Mapuche weaving, and Amazonian ceramics sustained living heritage.

Movement and Interaction Corridors

Continental circulation reached unprecedented scale:

-

Migration: European settlers (Italian, German, Spanish, Japanese) repopulated Brazil, Argentina, Chile, and Uruguay; internal migration urbanized Andean and coastal cities.

-

Rivers and rails: The Amazon, Paraguay, and Magdalena bound hinterlands to export ports.

-

Trade: Coffee, copper, nitrates, beef, and wool flowed to Atlantic and Pacific markets; oil joined after 1910.

-

Integration projects: Early customs unions evolved into the ABC Pact (Argentina–Brazil–Chile) and the Latin American Free Trade Association (1960).

-

Frontier expansion: Settlers, surveyors, and soldiers extended national authority into Amazonian forests and Patagonian plains, binding peripheries to capitals.

Cultural and Symbolic Expressions

Nations built mythologies of liberation and progress.

Romantic and modernist writers—José Hernández, Machado de Assis, Rubén Darío, Gabriela Mistral, Pablo Neruda, and Jorge Luis Borges—forged continental literatures. Visual art ranged from Andean costumbrismo to Mexican and Brazilian muralism, celebrating Indigenous and African heritage as foundations of identity.

Catholicism remained pervasive yet plural: popular pilgrimages and saints’ festivals persisted beside secular nationalism and new Protestant and Spiritist movements.

In the south, national narratives glorified frontier conquest; in the north, Andean and Amazonian cosmologies reemerged through indigenismo. Across the continent, dance and music—samba, tango, cueca, candombe, and vallenato—embodied the fusion of African, Indigenous, and European rhythms.

Environmental Adaptation and Resilience

Traditional ecological systems endured beneath modernization:

Andean terraces and irrigation persisted; Amazonian forest gardens maintained biodiversity; smallholders and Indigenous communities adapted global crops—potatoes, maize, cassava—to local microclimates.

Mechanized agriculture and deforestation redefined landscapes: soybean expansion in Brazil, sheep and wheat in Patagonia, sugar and cotton in northeast Brazil.

By the 1960s, environmental awareness emerged—parks in the Andes, conservation on Juan Fernández, and debates over Amazonian deforestation signaling a new consciousness of ecological limits.

Technology and Power Shifts (Conflict Dynamics)

The century and a half after independence was marked by recurring upheaval:

-

Wars and diplomacy: The War of the Triple Alliance (1864–1870), War of the Pacific (1879–1883), and border arbitrations defined national boundaries.

-

Social transformation: Abolition of slavery (Brazil, 1888), land reforms (Bolivia, Mexico, mid-20th century), and peasant mobilization challenged oligarchies.

-

Political cycles: Liberal republics gave way to populist and military regimes—Vargas in Brazil, Perón in Argentina, Velasco Alvarado in Peru—each promising modernization and social justice.

-

Revolution and reaction: Bolivia’s 1952 revolution, Cuba’s 1959 example, and guerrilla movements in Colombia and Venezuela framed Cold War geopolitics.

-

Southern frontiers: Argentina and Chile militarized Patagonia and Tierra del Fuego; Britain maintained the Falklands; boundary disputes simmered through the 20th century.

Technological change—aviation, electrification, oil extraction, and hydroelectric power—accelerated modernization while deepening regional inequality.

Transition (to 1971 CE)

By 1971, South America was a continent of contradictions: industrial cities beside impoverished rural zones, democratic ideals shadowed by coups, and booming exports amid environmental decline.

In the north, Brazil, Venezuela, and Colombia led industrial and oil economies; in the south, Argentina, Chile, and Uruguay oscillated between prosperity and political crisis.

The Amazon, Andes, and Patagonia—long the continent’s ecological and symbolic pillars—entered the modern age as frontiers of extraction, conservation, and imagination.

From the Inca terraces to the steel towers of São Paulo, from the Guiana forests to the Falklands sheep ranges, South America by 1971 stood as a continent unified by geography yet divided by history—its republics striving toward equity, identity, and stewardship in a world it had long supplied, inspired, and endured.

Groups

- Mapuche (Amerind tribe)

- Christians, Roman Catholic

- Chile, Republic of

- Paraguay, Republic of

- Colombia, Republic of (Gran Colombia)

- Peru, Republic of

- Brazilian Empire

- Bolivia, Republic of

- Uruguay, Eastern Republic of

- Venezuela, Bolivarian Republic of

- Ecuador, Republic of

- Argentine Confederation

- Chile, (Conservative) Republic of

- Peru-Bolivian Confederation

- Bolivia, Republic of

- Peru, Republic of

- Buenos Aires, State of

- Argentina (Argentine Republic)

- Chile, (Liberal) Republic of

- Colombia, United States of

- Colombia, Republic of

- Brazil, Federative Republic of

- Chile, (Parliamentary) Republic of

- Panama, Republic of

- Chile, (Presidential) Republic of

Topics

- Atlantic slave trade

- Araucanía, Occupation of

- Paraguayan War (López War or War of the Triple Alliance)

- Conquest of the Desert

- Chaco War

- Cold War

Commodoties

- Gem materials

- Domestic animals

- Grains and produce

- Fibers

- Strategic metals

- Slaves

- Sweeteners

- Industrial chemicals

- Stimulants

- Rubber

- Telecommunications