Raja Raja also expands his conquests in …

Years: 999 - 999

Raja Raja also expands his conquests in the north and northwest.

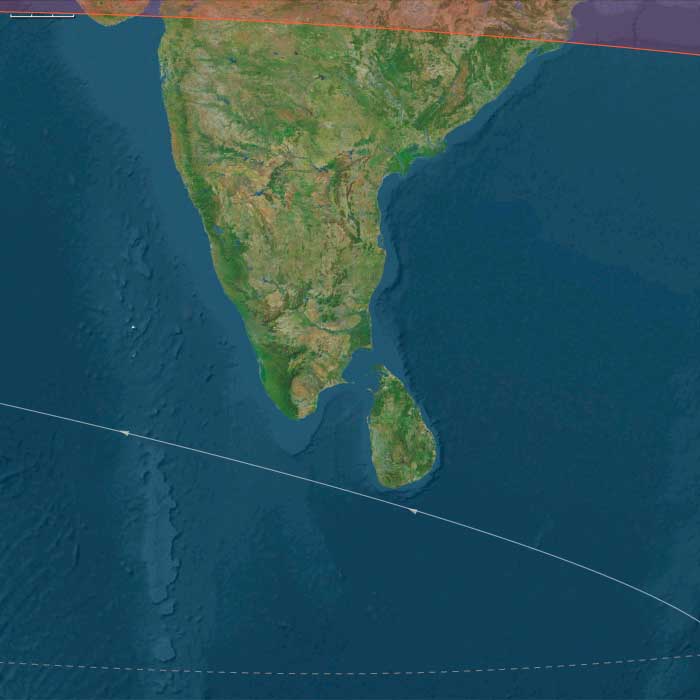

Before his fourteenth regnal year, around 998–999, Raja Raja conquers Gangapadi (Gangawadi) and Nurambapadi (Nolambawadi), which form part of the present Karnataka State.

This conquest is facilitated by the fact the Cholas have never lost their hold of the Ganga country from the efforts of Sundara Chola.

Nolambas, who are the feudatories of Ganga, who form the chief bulwark against the Chola armies in the northwest, could have turned against their overlords and aided the Cholas to conquer the Gangas.

The invasion of the Ganga country is a success and the entire Ganga country will be under the Chola rule for the next century.

The easy success against the Gangas is also due to the disappearance of the Rashtrakutas around 973, as they had been conquered by the Western Chalukyas.

From this time, the Chalukyas become the main antagonists of Cholas in the northwest.

To counter the interference of the Western Chalukyas, Raja Raja supports Saktivarman I, an Eastern Chalukya prince who is in exile in the Chola country.

He invades Vengi in 999 to restore Saktivarman to the Eastern Chalukya throne.

Locations

People

Groups

- Tamil people

- Pandyan Dynasty

- Chera dynasty

- Western Ganga Dynasty

- Chalukyas, Eastern, Rajput Kingdom of

- Chola Empire

- Western Chalukya Empire

- Kandy, Sinhalese Kingdom of

Topics

Commodoties

Subjects

Regions

Subregions

Related Events

Filter results

Showing 10 events out of 17 total

Northeastern North America

(1804 to 1815 CE): Exploration, Conflict, and Emerging National Identity

The years 1804 to 1815 in Northeastern North America marked an era of pivotal exploration, territorial expansion, intense conflicts, and significant developments shaping American national identity. During this period, Americans eagerly pursued westward expansion, leading to prolonged conflicts known as the American Indian Wars, while the Louisiana Purchase of 1803 nearly doubled the nation's size. Intensified slavery, frontier settlement, and evolving political landscapes also characterized this era, culminating in the War of 1812, a conflict that strengthened American nationalism despite its ambiguous conclusion.

Landmark Western Exploration

Lewis and Clark Expedition (1804–1806)

Following the Louisiana Purchase (1803), championed by the third U.S. president, Thomas Jefferson, the historic expedition led by Meriwether Lewis and William Clark, known as the Corps of Discovery, explored territories west of the Mississippi River. Their journey to the Pacific Ocean and back significantly expanded geographic and scientific understanding of the continent.

Zebulon Pike’s Explorations (1805–1807)

Explorer Zebulon Pike simultaneously conducted extensive explorations, mapping the Upper Mississippi River region and the southern parts of the newly acquired Louisiana Territory, enhancing U.S. knowledge of its expanding frontier.

Frontier Settlement and Westward Expansion

The Louisiana Purchase encouraged a vast wave of American settlers to push westward beyond the Appalachians. The frontier reached the Mississippi River by 1800, and new states such as Ohio (1803) were rapidly admitted into the Union. Settlements expanded into the Ohio Country, the Indiana Territory, and the lands of the lower Mississippi valley, particularly around St. Louis, which, after 1803, became a major gateway to the West. Americans enthusiastically pursued opportunities in new territories, sparking tensions and conflict with indigenous peoples.

In South Carolina, the antebellum economy flourished, particularly through cotton cultivation after Eli Whitney's invention of the cotton gin in 1793. Though nominally democratic, South Carolina remained tightly controlled by a powerful planter elite, with strict property and slaveholding requirements limiting political participation to wealthy landowners.

War of 1812 and Its Impacts

Causes and Conflicts

The U.S. declared war against Great Britain in 1812, motivated by grievances such as impressment of American sailors, trade restrictions, and Britain's support for Native American resistance. Prominent Federalist leaders, including Boston-based politician Harrison Gray Otis, strongly opposed the war, advocating states' rights at the Hartford Convention (1814).

Combat and Indigenous Alliances

Intense battles occurred along the Canadian-American frontier. Native leaders like Tecumseh allied with Britain, resisting American westward expansion until Tecumseh's defeat and death at the Battle of the Thames (1813). The war saw notable events such as the British burning of Washington D.C. (1814) and the failed British assault on Baltimore, immortalized by Francis Scott Key's poem "The Star-Spangled Banner."

Conclusion and National Identity

Ending in stalemate with the Treaty of Ghent (1814), the war nonetheless bolstered U.S. nationalism and confirmed the nation's resilience. The final American victory at the Battle of New Orleans (January 1815) elevated Andrew Jackson as a national hero.

Social, Economic, and Cultural Developments

Expansion of Slavery and Southern Economy

Despite the ideals of liberty proclaimed in the American Revolution, slavery expanded dramatically in the Deep South. Following the failed Gabriel’s Rebellion (1800) in Virginia, Southern planters imposed even harsher controls on enslaved people. By 1810, South Carolina had a large enslaved population—nearly half of its residents—essential for its thriving cotton economy. Powerful merchant families, such as the Boston-based Cabots and Perkins, continued amassing wealth through shipping and involvement in slave-related trade, exemplifying the complex intersections of commerce, slavery, and politics.

Religious Revival and Frontier Culture

The Second Great Awakening profoundly influenced frontier society, encouraging evangelical Protestant revivals, camp meetings, and increased participation in denominations like Baptists and Methodists. Large camp meetings, including the famous gathering at Cane Ridge, Kentucky (1801), energized religious life and social reform movements.

Jeffersonian Democracy and Early Political Developments

Thomas Jefferson, a leading advocate for individual liberty and separation of church and state, profoundly shaped U.S. politics in the early 1800s. Serving as president from 1801 to 1809, he oversaw the Louisiana Purchase, which significantly expanded the nation's territory. Despite advocating democratic ideals, Jefferson himself exemplified contradictions: he was an eloquent champion of freedom who remained economically reliant on enslaved labor at his plantation home, Monticello, and was likely father to several children with Sally Hemings, an enslaved African-American woman.

Jefferson and his successor, James Madison (1809–1817)—both clean-shaven like their predecessors, Washington and Adams—oversaw the complex diplomatic tensions and conflicts culminating in the War of 1812.

Domestic Turmoil and Conspiracy

During this era, internal U.S. affairs were unsettled. The Spanish withdrawal of the American “right of deposit” at New Orleans (1802) escalated tensions, fueling discussions of war. The controversial third vice-president, Aaron Burr, became embroiled in scandal, allegedly conspiring in 1805–1807 to foment secession in the western territories alongside General James Wilkinson. Although his conspiracy remains debated among historians, it highlighted the fragility of national unity during this period.

International Commerce and Opium Trade

Prominent American merchant families such as the Cabots of Boston continued to build fortunes through shipping, privateering, and participation in the Triangular Trade involving enslaved Africans. Samuel Cabot Jr., through marriage to Eliza Perkins, daughter of merchant king Colonel Thomas Perkins, expanded family wealth by engaging in controversial opium trade with China via British smugglers, highlighting the far-reaching commercial interests of prominent American families during this period.

Additionally, major institutions like Brown University began confronting the economic legacy of slavery, addressing their involvement in slave trading as well as their complex roles in the nation’s commercial and academic development.

Native American Realignment and the American Indian Wars

American eagerness for westward expansion led to escalating violence and displacement of indigenous peoples. During the War of 1812, some Native tribes allied with the British as a strategy against American expansion. However, the defeat of Native coalitions severely weakened resistance, enabling accelerated settler encroachment on indigenous territories. Tribes like the Mandan, Assiniboine, and Crow faced ongoing conflicts, devastating epidemics, and the pressures of expanding American settlements.

Legacy of the Era (1804–1815 CE)

From 1804 to 1815, Northeastern North America witnessed transformative developments shaping national identities, geopolitical alignments, and social structures. The era was defined by dramatic territorial growth through the Louisiana Purchase, intense frontier conflict, expanded slavery, profound religious awakenings, and political controversies. While the War of 1812 tested American resilience, it ultimately strengthened the nation's identity. Simultaneously, the persistence and expansion of slavery deepened social divisions that would have profound consequences for decades to follow.

Eli Whitney's cotton gin has rejuvenated the plantation slavery industry and therefore an important if unintended cause of the American Civil War in the early 1860s.

Slavery had been on the decline before the invention of the cotton gin; many slaveholders had even given away their slaves, including George Washington

The cotton gin has transformed Southern agriculture and the national economy.

Southern cotton finds ready markets in Europe and in the burgeoning textile mills of New England.

Cotton exports from the U.S. had boomed after the cotton gin's appearance—from less than five hundred thousand pounds (two hundred and thirty thousand kilograms) in 1793 to ninety-three million pounds by 1810.

Cotton is a staple that can be stored for long periods and shipped long distances, unlike most agricultural products.

It will soon become the chief export of the United States, representing over half the value of the country's exports from 1820 to 1860.

Paradoxically, the cotton gin, a labor-saving device, helps preserve slavery in the U.S.

Before the 1790s, slave labor was primarily employed in growing rice, tobacco, and indigo, none of which were especially profitable any longer.

Neither was cotton, due to the difficulty of seed removal, but with the gin, growing cotton with slave labor has become highly profitable—the chief source of wealth in the American South, and the basis of frontier settlement from Georgia to Texas.

"King Cotton" has become a dominant economic force, and slavery is sustained as a key institution of Southern society.

Spain had agreed in the secret Treaty of San Ildefonso of 1800 to return Louisiana to France in the secret Treaty of San Ildefonso of 1800; however, the boundaries are not explicitly specified.

After France sells the Louisiana Purchase to the United States in 1803, another boundary dispute had erupted.

The United States lays claim to the territory from the Perdido River (which today forms part of the boundary between the the U.S. states of Alabama and Florida along nearly its entire length and drains into the Gulf of Mexico) to the Mississippi River, which the Americans believe had been a part of the old province of Louisiana when the French had agreed to cede it to Spain in 1762.

The Spanish insist that they had administered that portion as the province of West Florida and that it was not part of the territory restored to France by Charles IV in 1802, as France had never given West Florida to Spain, among a list of other reasons.

The United States and Spain have held long, inconclusive negotiations on the status of West Florida.

In the meantime, American settlers have established a foothold in the area and resisted Spanish control.

British settlers, who had remained, also resented Spanish rule, leading to a rebellion in 1810 and the establishment for seventy-four days of the Republic of West Florida.

Many secret meetings of those who resent Spanish rule, as well as three openly held conventions, take place in the Baton Rouge district in West Florida from June to September 1810.

Out of those meetings grows the West Florida rebellion and the establishment of the independent Republic of West Florida, with its capital at St. Francisville, in present-day Louisiana, on a bluff along the Mississippi River.

The rebels unfurl the flag of the new republic, a single white star on a blue field.

After the successful attack, organized by Philemon Thomas, plans are made to take Mobile and Pensacola from the Spanish and incorporate the eastern part of the province into the new republic.

Thomas, born in Virginia, had served in the American forces during Revolutionary War and later moved to Kentucky.

He was a member of Kentucky's Constitutional Convention and served in the state House and state Senate before moving to Louisiana in 1806.

Born in Fauquier County, Virginia, Kemper and his brothers Nathan and Samuel had settled in Feliciana Parish, near Baton Rouge, Spanish West Florida, shortly after 1800.

Expelled from the province by the Spanish authorities in a dispute over land titles, the Kemper brothers had organized a small force in the Mississippi Territory and returned, declaring West Florida to be independent.

They had attempted to capture Baton Rouge in 1804, but were defeated, having failed to gain the support of local Anglo-American settlers.

Most of the latter were satisfied with Spanish rule on account of Spain's liberal land grants and its protection of slavery.

The following year Spanish forces had captured all three brothers while they were on U.S. soil, but American forces had rescued them as they were being taken down the Mississippi River.

In 1810, during the rebellion against Spanish rule by British and Anglo-American settlers (who comprised the majority of inhabitants), Reuben Kemper and Joseph White are authorized to invite the inhabitants of Mobile and Pensacola to join in the revolt.

When Kemper crosses into the Mississippi Territory, U.S. forces arrest him, as they do not wish to provoke Spain into war and fear Kemper's intentions.

He is more fortunate than his colleagues, who are seized by the Spanish authorities and sent as prisoners to El Morro, in Havana, Cuba, but the rebellion spreads.

The faction that favors the continued independence of West Florida secures the adoption of a constitution at a convention in October.

The convention had earlier commissioned an army under General Philemon Thomas to march across the territory, subdue opposition to the insurrection, and seek to secure as much Spanish-held territory as possible.

"Residents of the western Florida Parishes proved largely supportive of the Revolt, while the majority of the population in the eastern region of the Florida Parishes opposed the insurrection. Thomas' army violently suppressed opponents of the revolt, leaving a bitter legacy in the Tangipahoa and Tchefuncte River region." (Christina Chapple, quoting Southeastern Louisiana history professor Sam Hyde, in "Commission planning for West Florida Republic bicentennial" on the Southeastern Louisiana University web site, posted July 6, 2009 (accessed March 25, 2018).

The Pearl River with its branch that flows into the Rigolets forms the eastern boundary of the republic.

On October 27, 1810, U.S. President James Madison had proclaimed that the United States should take possession of West Florida between the Mississippi and Perdido Rivers, based on a tenuous claim that it is part of the Louisiana Purchase.

The West Florida government opposes annexation, preferring to negotiate terms to join the Union.

Governor Fulwar Skipwith proclaims that he and his men will "surround the Flag-Staff and die in its defense."

William C. C. Claiborne is sent to take possession of the territory, entering the capital of St. Francisville with his forces on December 6, 1810.

A week later, he and many of his fellow officials still lingered at St Francisville preparing to go to Baton Rouge, where the next session of the legislature is to consider his ambitious program.

The impending U.S. takeover apparently comes as a surprise to Skipwith when the Mississippi Territory governor, David Holmes, and his party approach the town.

Holmes persuades all except a few leaders, including Skipwith and Philemon Thomas, the general of the West Florida troops, to acquiesce to American authority.

Skipwith complains bitterly to Holmes that, as a result of seven years of U.S. tolerance of continued Spanish occupation, the United States has abandoned its right to the country and that the West Florida people will not now submit to the American government without conditions.

Skipwith and several of his unreconciled legislators now depart for the fort at Baton Rouge, rather than surrender the country unconditionally and without terms.

European-Americans in the Louisiana area worry about slave uprisings fueled by the spread of ideas of freedom from the French and Haitian revolutions.

The German Coast—in St. Charles and St. James Parishes, Louisiana—is an area of sugar plantations, with a dense population of enslaved people.

Blacks outnumber whites by nearly five to one according to some accounts.

More than half of those enslaved may have been born outside Louisiana, many in Africa.

The free black population in the overall Territory of Orleans has nearly tripled from 1803 to 1811 to five thousand, with three thousand arriving in 1809–1810 as migrants from Haiti (via Cuba), where in Saint-Domingue they had enjoyed certain rights as gens de couleur.

Territorial Governor William C.C. Claiborne has struggled with the diverse population since the U.S. negotiated the Louisiana Purchase in 1803.

Not only are there numerous French and Spanish-speaking people, but there is a much greater proportion of native Africans among the enslaved than in more northern U.S. states.

In addition, the mixed-race Creole and French-speaking population has grown markedly with refugees from Haiti following the successful slave revolution.

The American Claiborne is not used to a society with the number of free people of color that Louisiana has—but he works to continue their role in the militia that had been established under Spanish rule.

He has to deal with the competition for power between long-term French Creole residents and new U.S. settlers in the territory.

Lastly, Claiborne is suspicious that the Spanish might encourage an insurrection.

He struggles to establish and maintain his authority.

The waterways and bayous around New Orleans and Lake Pontchartrain make transportation and trade possible, but also provide easy escapes and nearly impenetrable hiding places for runaway slaves.

Some maroon colonies have continued for years within several miles of New Orleans.

The largest slave revolt in American history, the 1811 German Coast Uprising, takes place just outside of New Orleans.

Between sixty-four and five hundred enslaved people rise up on the German Coast forty miles outside of New Orleans, and march to within twenty miles (thirty-two kilometers) of the city gates.

The revolt takes the entire military might of the Orleans Territory to suppress and is the greatest threat to American sovereignty in New Orleans.

Years: 999 - 999

Locations

People

Groups

- Tamil people

- Pandyan Dynasty

- Chera dynasty

- Western Ganga Dynasty

- Chalukyas, Eastern, Rajput Kingdom of

- Chola Empire

- Western Chalukya Empire

- Kandy, Sinhalese Kingdom of