Polynesia (2637 – 910 BCE): Lapita Horizons, …

Years: 2637BCE - 910BCE

Polynesia (2637 – 910 BCE): Lapita Horizons, Voyaging Science, and the Unreached North

Regional Overview

Across the open Pacific, Polynesia lay poised for its first true colonization.

While the great civilizations of Eurasia turned to bronze, iron, and empire, this oceanic world entered an age of exploration defined not by metals but by canoes, stars, and memory.

Between the mid-third and early first millennium BCE, Austronesian voyagers—descendants of Lapita pioneers—pushed eastward from the Bismarck and Fijian arcs, testing routes that would one day span a third of the globe.

The southern frontier, in Tonga and Samoa, saw permanent settlement by about 900 BCE.

Farther east and north, the Societies, Marquesas, Hawaiʻi, and Rapa Nui remained pristine: mapped in mind, not yet in habitation.

Geography and Environmental Context

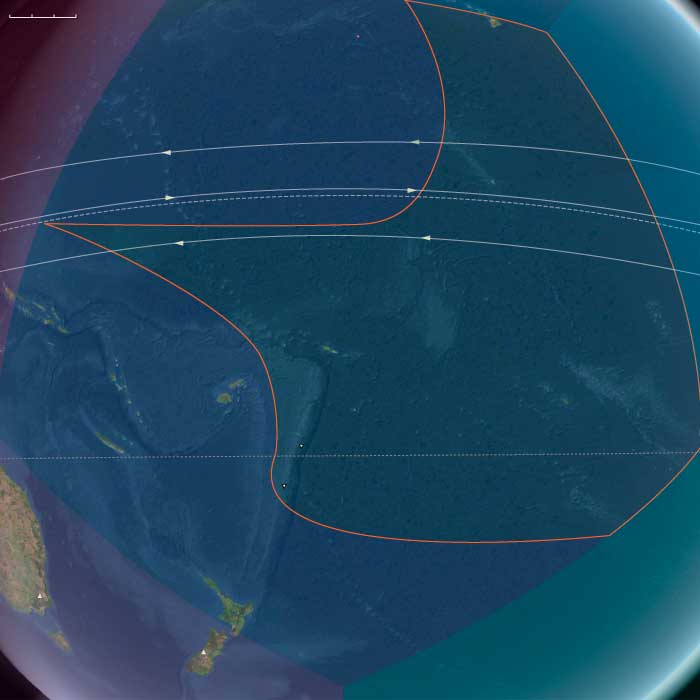

The Polynesian triangle—bounded by future Hawaiʻi, New Zealand, and Rapa Nui—was still largely empty of people.

To the south and west, Lapita societies thrived along the Fiji–Tonga–Samoa axis, a zone of fertile volcanic soils, reef-sheltered coasts, and abundant breadfruit and taro.

Northward stretched the high, forested islands of the Hawaiian chain and the remote atoll of Midway; eastward, the volcanic peaks of the Societies and Marquesas, the coral ridges of the Cooks, and the lonely cones of Rapa Nui and Pitcairn awaited discovery.

Across these immense distances, the Pacific’s trade winds, countercurrents, and celestial regularities provided the framework for navigation.

Climate and Environmental Shifts

Holocene stability reigned.

Regular trade-wind seasons, interspersed with localized droughts and Kona-type storms, defined the pattern familiar through later millennia.

Sea levels had stabilized close to modern elevations, lagoons and atolls matured ecologically, and coral reef systems reached their pre-human equilibrium—a pristine baseline soon to host the transported landscapes of Polynesian horticulture.

Societies, Settlement, and Expansion

By the early first millennium BCE, Lapita communities from Near Oceania had developed into full maritime chiefdoms.

They founded Tonga and Samoa, bringing with them domesticated animals, tubers, tree crops, and an integrated horticultural–fishing economy.

Their settlements, organized around coastal hamlets and beach-ridge cemeteries, formed the first enduring societies in what would become Polynesia proper.

These colonists combined intricate kinship systems with lineage-based authority expressed through exchange and feasting.

Beyond them, the high islands and atolls of central and northern Polynesia remained unvisited—the last great frontier of the human voyage.

Economy and Technology

Lapita subsistence depended on mixed horticulture, arboriculture, and reef harvesting.

Stone and shell adzes, barkcloth looms, and obsidian tools underpinned daily life.

Pottery—characterized by its distinctive dentate-stamped designs—served as both utilitarian ware and a marker of cultural identity.

The real technological revolution, however, lay in seamanship: the refinement of the double-hulled canoe, the balanced crab-claw sail, and the astronomical navigation system that made deliberate ocean crossings routine.

These innovations transformed the Pacific from a barrier into a continent of water.

Movement and Interaction Corridors

A dense voyaging corridor linked Fiji, Tonga, and Samoa, forming the nucleus of the later Polynesian exchange sphere.

Exploratory probes reached eastward toward the Cook and Society Islands and northward into uncharted waters, where Hawaiʻi’s volcanic silhouettes awaited future landfall.

Each expedition tested wind patterns, star paths, and ocean swells, gradually extending the mental map of the ocean.

The Lapita maritime network thus became the laboratory from which Polynesian wayfinding emerged.

Belief and Symbolism

Lapita iconography—incised faces, spirals, and concentric motifs—encoded ancestral and cosmological themes, linking the sea, lineage, and creation.

Sacred beach terraces, aligned to the horizon, may represent early forms of marae or ahu, foreshadowing the ritual architecture of later Polynesia.

Voyaging itself was a sacred act: canoes were consecrated, navigators initiated, and landfalls interpreted as fulfillments of ancestral design.

Environmental Adaptation and Resilience

Colonists transported a complete biocultural package—taro, yam, breadfruit, coconut, pig, dog, chicken, and the social institutions to manage them.

They sited villages in leeward zones sheltered from cyclones, practiced intercropping for soil stability, and established portable ecosystems that could regenerate on any new island.

In yet-unsettled regions, natural ecosystems continued undisturbed, providing the environmental blank slate that later settlers would transform into productive landscapes.

Regional Synthesis and Long-Term Significance

By 910 BCE, Tonga and Samoa stood as the Lapita world’s eastern bastions, while the vast remainder of Polynesia remained silent and untouched.

Yet every element of the later Polynesian achievement was already in place—the technology, cosmology, and navigational genius that would soon knit the central and northern Pacific into a single cultural sphere.

This epoch thus represents Polynesia in potential: a constellation of islands awaiting connection, its human story poised at the threshold of discovery.