Northern North America (964 – 1107 CE): …

Years: 964 - 1107

Northern North America (964 – 1107 CE): Salmon States, Mound Metropolises, and Desert Irrigators

Geographic and Environmental Context

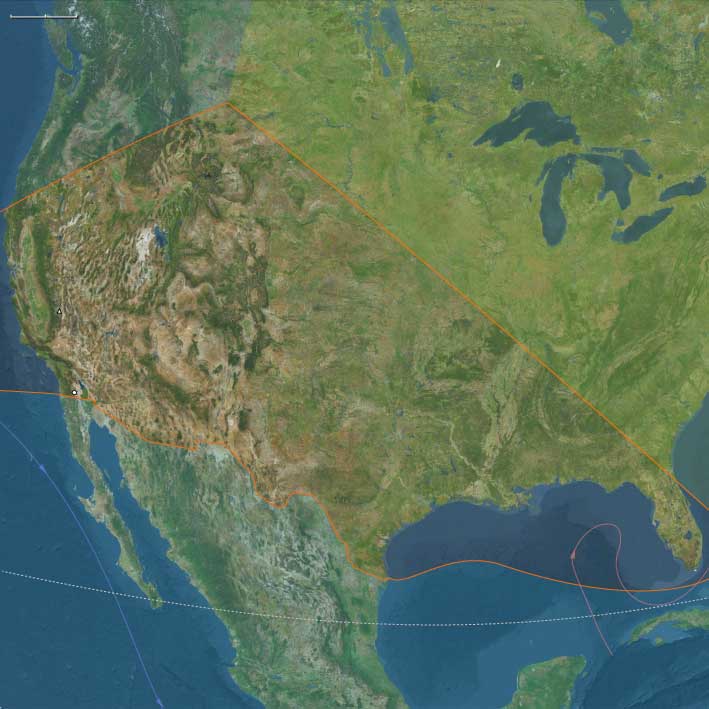

Northern North America stretched from the Gulf of Alaska and Haida Gwaii down the Salish Sea and Pacific coast to California, eastward across the Great Basin and Puebloan Southwest to the Mississippi–Ohio valleys, the Great Lakes–St. Lawrence corridor, and the Atlantic seaboard—and north to Greenland and the Canadian Arctic.

It encompassed:

-

Northwest Coast and Subarctic/Arctic: Tlingit, Haida, Tsimshian, Kwakwakaʼwakw, Coast Salish; Dene (Athabaskan) interiors; Yup’ik and Inupiat Inuit; Unangan (Aleut) and Sugpiaq/Alutiiq.

-

Northeast: Norse Greenland and Vinland outposts; Mississippian and Woodland centers from the St. Lawrence–Great Lakes to the Tallgrass Prairie; Iroquoian and Algonquian village belts; Old South/Appalachian chiefdoms; Thule expansion across the Arctic.

-

Gulf & Western: Lower Mississippi, Cahokia’s wider sphere, Spiro, Etowah, Moundville; Chaco Canyon roads and great houses; Hohokam irrigation in the Sonoran; Mogollon–Sinagua towns; Chumash littoral polities; Great Basin foragers.

Climate and Environmental Shifts

The Medieval Warm Period (c. 950–1250) stabilized and in places lengthened growing and navigation seasons.

-

Northwest Coast: heavy rainfall sustained massive cedar forests; salmon runs were reliable.

-

Subarctic/Arctic: slightly longer ice-free windows increased whaling opportunities, though sea-ice variability remained high.

-

Mississippi–Ohio valleys: warmth supported the maize boom and urbanization at Cahokia (c. 1050 onset).

-

Colorado Plateau/Sonoran: Chaco (1050–1130 zenith) flourished within favorable precipitation patterns; Hohokam irrigation buffered aridity.

-

California: oak savannas and coastal fisheries remained highly productive.

Societies and Political Developments

North Pacific Coast & Arctic

Stratified house-group chiefdoms on the coast managed ranked lineages, fishing/whaling grounds, and winter villages; potlatch intensified as theatrical redistribution of wealth and rights. Dene bands coordinated caribou/salmon circuits between taiga and rivers. Inuit developed large communal whale hunts and winter qasgiq ceremonial houses; Unangan and Sugpiaq organized maritime village clusters with leadership rooted in hunting prowess and boat building.

Northeast & Interior Woodlands

Norse Greenland stabilized farming and walrus-ivory exports; Vinland (Newfoundland) saw short-lived Norse ventures and conflict with local peoples. Cahokia emerged as a mound-metropolis with elite compounds, plazas, and woodhenges marking ritual calendars; Old South/Appalachian chiefdoms raised platform mounds. Iroquoianlonghouse communities and Algonquian riverine villages densified across the Great Lakes and St. Lawrence. On the tundra, Thule Inuit expanded eastward, replacing Dorset traditions.

Gulf & Western

Mississippian chiefdoms (Etowah, Moundville, Spiro) elaborated the Southeastern Ceremonial Complex; Spiro in the Arkansas Valley grew as a ritual–trade hub. In the Southwest, Chaco orchestrated a network of great houses, roads, and kivas; Hohokam enlarged canal systems and cotton/crop production; Mogollon–Sinagua towns persisted as mixed-farming communities. Along the Channel coast, Chumash intensified a bead-currency maritime economy; Great Basin societies deepened pinyon and exchange lifeways.

Economy and Trade

-

Coast & Arctic: salmon surpluses (dried/smoked) underwrote population and ceremony; eulachon (oolichan) oil traveled inland along Grease Trails; native copper from Yukon/interior circulated as ingots and hammered regalia; dentalium shells moved north from California; ivory, baleen, and marine oils flowed through Dene and coastal brokers.

-

Mississippian & Woodlands: maize redistribution centered on Cahokia; exchange of copper, shell gorgets, chert, ceremonial pipes; Great Lakes/Atlantic fisheries supported dense coastal and riverine communities. Greenland Norse exported walrus ivory to Europe.

-

Southwest & California: Chaco networks trafficked turquoise, obsidian, macaws; Hohokam moved cotton, shell jewelry, and irrigation produce; Chumash circulated shell-bead currency, tying Pacific routes to interior markets; Great Basin moved salt and obsidian into Pueblo worlds.

Subsistence and Technology

-

Northwest Coast: monumental cedar plank houses, crest poles, and raised granaries; large red-cedar dugout canoes for freight, warfare, and ceremony; smokehouses and oil-rendering vats for preservation.

-

Arctic: qayaq and umiak, toggling harpoons, composite bows; sophisticated sea-ice knowledge.

-

Dene & Interior: sinew-backed bows, birchbark canoes, snowshoes, toboggans; flexible river–taiga scheduling.

-

Mississippi–Woodlands: earthwork engineering (platform mounds, causeways), woodhenges as calendrical devices, diversified maize–bean–squash regimes.

-

Southwest: multistory great houses, road alignments, and kiva architecture at Chaco; canal engineering and cotton textiles among Hohokam.

-

California: plank canoes (tomols) in the south, advanced fish weirs and acorn-processing economies; formalized bead production.

Movement and Interaction Corridors

-

Inside Passage knit Haida Gwaii–Tlingit fjords–Kwakwakaʼwakw sounds–Salish inlets; Yukon and Copper Rivers linked Dene to coastal fairs.

-

Grease Trails carried oolichan oil, furs, obsidian coast⇄plateau.

-

Bering Strait enabled Inuit–Chukchi trans-Arctic ties.

-

St. Lawrence–Great Lakes funneled goods between interior and Atlantic; Ohio–Mississippi corridors radiated from Cahokia.

-

Chaco roads connected canyon centers to outliers; Hohokam canals concentrated production and exchange.

-

Pacific littoral linked Chumash and northern neighbors via shell currency and canoe voyaging.

Belief and Symbolism

-

Northwest Coast: clan crests (Raven, Eagle, Killer Whale, Wolf) encoded lineage titles and narrative rights; potlatch dramatized myth cycles and law.

-

Arctic: whale/seal rituals honored prey spirits; qasgiq dances renewed communal bonds.

-

Dene: shamanic guardians, vision quests, and narrative law aligned subsistence with morality.

-

Mississippian: the Southeastern Ceremonial Complex (birdman, serpent) expressed elite cosmology; Cahokia’s mounds and woodhenges synchronized ritual and polity.

-

Southwest: kiva ceremonialism ordered time, space, and society; macaw/turquoise regalia symbolized distant connections.

-

California littoral: Chumash cosmology elevated canoe chiefs as celestial navigators within a star-mapped sea.

Adaptation and Resilience

-

Ecological scheduling: sequential harvests (salmon→eulachon→berries/deer; maize→nuts/fish; pinyon→game) spread risk.

-

Preservation technologies (smoking, drying, oil rendering) created buffers against shortfalls.

-

Redundant corridors—river, coastal, and road networks—re-routed flows during conflict or climate swings.

-

Ceremonial redistribution (potlatch, mound-center feasts, kiva rites) translated surplus into social stability and intergroup diplomacy.

-

Water/land engineering (Hohokam canals, Chaco roadworks, fish weirs) extended carrying capacity.

Long-Term Significance

By 1107 CE, Northern North America sustained three synergistic civilizational zones:

-

A salmon-and-cedar coast of ranked chiefdoms and potlatch law, integrated with Dene interiors and Inuit Arctic whaling.

-

A mound-metropolis heartland centered on Cahokia, radiating ceremonial, economic, and political influence across the Mississippi and Old South.

-

A desert–littoral innovation belt where Chaco ritual economies, Hohokam irrigation cities, and Chumash sea commerce tied the interior to the Pacific.

Norse Greenland and brief Vinland contacts bookended the Atlantic frontier, while cross-continental exchange in copper, shells, oil, ivory, turquoise, and maize linked forests, plains, deserts, and seas. The balance of ritual prestige, ecological scheduling, and engineered landscapes laid a durable foundation for the monumental art, intensified warfare, and widening trade spheres of the 12th–13th centuries.

Groups

- Kwakwakaʼwakw

- Coast Salish

- Haida people

- Tlingit people

- Athabaskans, or Dene, peoples

- Nuu-chah-nulth people (Amerind tribe; also formerly referred to as the Nootka, Nutka, Aht, Nuuchahnulth)

- Tsimshian

- Thule Tradition, Punuk and Birnirk Stages

- Inuit

- Inupiat

- Gwichʼin

- Kaska Dena

- Dakelh

- Tahltan

- Aleut people

- Yupʼik

Commodoties

Subjects

- Commerce

- Watercraft

- Sculpture

- Painting and Drawing

- Environment

- Decorative arts

- Mayhem

- Government

- Custom and Law

- Technology