Northern North America (909 BCE – 819 …

Years: 909BCE - 819

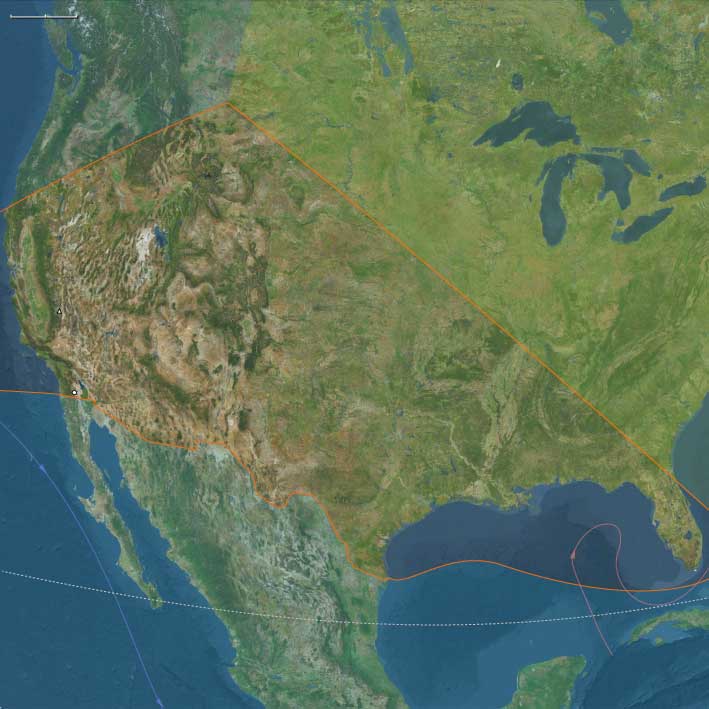

Northern North America (909 BCE – 819 CE): From Arctic Seas to Riverine Towns — The Deep Foundations of the Continent

Regional Overview

From the drifting pack ice of the Arctic Ocean to the salmon canyons of the Fraser and Columbia, and from the birch forests of the Great Lakes to the mounds of the Mississippi, Northern North America in the first millennium BCE through the early centuries CE formed a continental lattice of waterways, fisheries, and overland trails.

Across this vast region, societies diversified around the rhythm of rivers and the reach of coastlines — Arctic seal hunters, Pacific longhouse chiefs, Woodland farmers, and Plains foragers each adapting to their ecologies while linked through far-flung exchange.

By 819 CE, the northern half of the continent had achieved a remarkable cultural equilibrium: stable regional traditions, robust interzonal trade, and the institutional seeds that would flower into the Thule migrations, Mississippian towns, and Northwest Coast chiefdoms of the coming age.

Geography and Environment

Northern North America embraced the Arctic littoral, the North Pacific coast, the continental interior, and the temperate forests bordering the Atlantic.

-

The Arctic and subarctic stretched from the Yukon to Baffin Bay, its coasts ruled by sea-ice cycles and river estuaries rich in fish and seals.

-

The Northwest Coast offered mild, wet climates and dense conifer forests, sustaining some of the highest population densities north of Mesoamerica.

-

The Interior Plains and Plateaus were threaded by the Mississippi, Missouri, and Columbia systems — arteries of migration and exchange.

-

The Northeastern woodlands combined mixed farming with forest hunting, while the Great Lakes and St. Lawrence corridors linked interior and Atlantic ecologies.

Climatic variability shaped mobility rather than collapse: alternating warm and cool pulses adjusted the balance between farming and foraging, while vast ecological diversity ensured regional resilience.

Societies and Political Developments

Arctic and Subarctic Horizons

In the western Arctic, the Norton tradition (c. 1000 BCE – 800 CE) established semi-subterranean house villages, oil-lamp economies, and net fisheries across Alaska’s bays and rivers.

By the mid-first millennium CE, Birnirk innovations — sea-ice whaling, toggling harpoons, refined bone and ivory craft — emerged on the North Slope, setting the technological stage for the Thule expansion.

Inland, Athabaskan foragers managed caribou and salmon cycles through flexible band networks stretching from the Yukon to the Mackenzie.

The North Pacific Coast

Southward, the ranked longhouse societies of the Haida, Tlingit, Tsimshian, and related peoples achieved a mature social hierarchy centuries before written history: hereditary chiefs, clan crests, and ceremonial redistribution through feast-traditions ancestral to the later potlatch.

Villages of massive cedar plank houses lined Haida Gwaii, the central BC fjords, and the Puget Sound.

Farther inland, Plateau communities along the Fraser and Columbia Rivers built pit-house towns near salmon canyons, tightly integrated with coastal exchange.

The Eastern Woodlands and Arctic Threshold

In the east, Late Woodland cultures consolidated from the Great Lakes to the Appalachians.

Fortified longhouse villages in Ontario and New York foreshadowed Iroquoian confederacies.

Southward along the Mississippi–Ohio system, mound centers continued the Hopewell legacy and anticipated Mississippian complexity.

On the Atlantic, shell-heap villages thrived from Chesapeake to the Gulf of Maine.

Farther north, Dorset Paleo-Inuit traditions persisted across the Eastern Arctic, with the coming Thule and, later, Norse Greenlanders still centuries ahead.

Economy and Trade

Across the region, economic life revolved around seasonal abundance and long-distance circulation.

-

Arctic and Subarctic peoples balanced sea-mammal hunting, fishing, and caribou herding, exchanging furs, ivory, and stone for metal and wood from the south.

-

Coastal chiefdoms specialized in salmon, eulachon oil, cedar timber, and carved prestige goods of copper and shell, exported inland along “grease trails.”

-

Interior and Woodland farmers combined maize, beans, and squash with hunting and fishing; their towns became marketplaces for copper, obsidian, mica, and shell ornaments.

-

River and lake corridors — Yukon, Fraser, Columbia, Mississippi, St. Lawrence — functioned as the highways of pre-Columbian North America, linking ecological zones into continental exchange.

Technology and Material Culture

Technological ingenuity was universal yet regionally distinct.

-

Arctic engineers developed the qayaq and umiak, bone-framed sleds, toggling harpoons, and oil lamps for polar survival.

-

Northwest Coast carpenters perfected adzes, chisels, and caulking for seaworthy canoes and monumental architecture.

-

Woodland artisans produced cord-marked pottery, copper ornaments, and polished stone tools.

-

Irrigation in the desert Southwest (to the south) influenced maize cultivation reaching the Lower Mississippi; meanwhile, storage pits, smoking racks, and plank granaries became standard food-security technologies across the temperate north.

Belief and Symbolism

Religious and ceremonial life bound ecology to ancestry.

-

Along the Pacific Coast, first-salmon rites, crest art, and mortuary feasts articulated kin identity and ecological reciprocity.

-

In the Woodlands, mound burials, clan totems, and cosmologies of the four directions organized both ritual and landscape design.

-

In the Arctic, shamanic traditions mediated between human and animal spirits, honoring the souls of seals, whales, and caribou.

Art, dance, and ritual reaffirmed the moral equilibrium between community and environment, making cosmology a practical guide for survival.

Adaptation and Resilience

Environmental diversity bred redundancy and cooperation.

Food storage, alliance marriages, and ritual feasting functioned as social insurance systems against famine or climatic shock.

Riverine and coastal corridors allowed mobility when drought, ice, or conflict disrupted one zone.

Technological convergence — woodcraft, metallurgy, navigation, and agriculture — produced a continental safety net of knowledge.

Regional Synthesis and Long-Term Significance

By 819 CE, Northern North America had matured into a web of complementary cultural systems:

-

Arctic Norton–Birnirk foragers poised for the Thule transformation;

-

Northwest Coast longhouse chiefdoms achieving classical complexity;

-

Interior and Woodland farmers consolidating the Late Woodland world;

-

Atlantic and Great Lakes peoples connecting interior and ocean through canoe exchange.

This mosaic — continental in scale yet locally precise — provided the infrastructure for the continent’s medieval efflorescence: Thule migrations across the Arctic, the rise of Cahokia and its mound-town network, and the flourishing of Northwest Coast monumental art.

In environmental and cultural resilience, Northern North America was already a mature world — one whose diversity and interconnection would shape the hemispheric story for centuries to come.

Groups

- Kwakwakaʼwakw

- Haida people

- Tlingit people

- Athabaskans, or Dene, peoples

- Klamath (Amerind tribe)

- Tsimshian

- Aleutian Tradition