Northern North America (49,293 – 28,578 BCE): …

Years: 49293BCE - 28578BCE

Northern North America (49,293 – 28,578 BCE): Upper Pleistocene I — Ice Margins, Continental Gateways, and the First Migrations

Geographic and Environmental Context

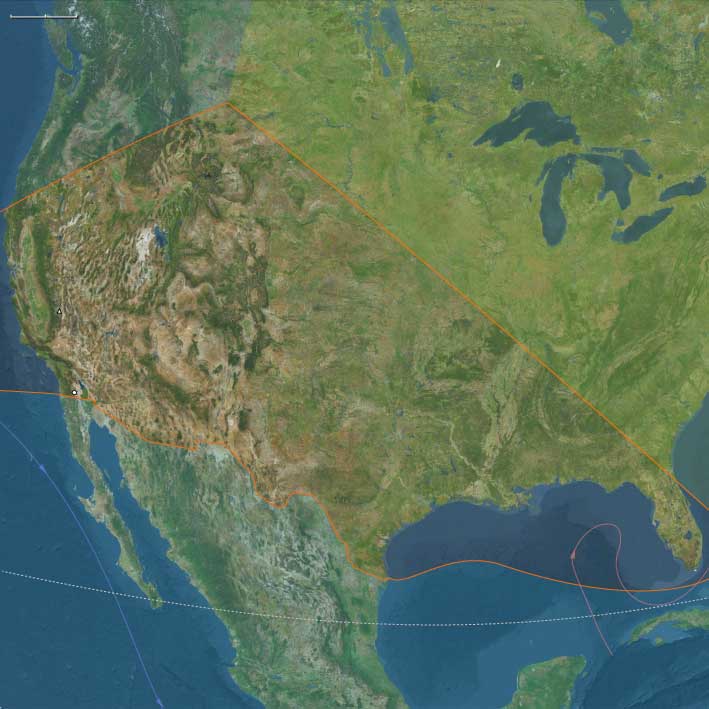

During the late Pleistocene, Northern North America stretched across a landscape undergoing immense geological transformation. The advance and retreat of the Laurentide and Cordilleran ice sheets shaped a continent of alternating refugia and barriers. The region’s three great subregions—Northwestern, Northeastern, and Gulf & Western North America—each represented a distinctive interface between ice, land, and sea.

-

Northwestern North America bridged Asia and the Americas through the vast, exposed Beringian landmass. Grassy steppes, braided rivers, and polynyas along the Bering and Chukchi shelves linked Siberia to Alaska.

South of the continental ice, the Yukon and Kuskokwim basins opened to interior plains and the Gulf of Alaska’s wide glacial fjords. -

Northeastern North America was dominated by the Laurentide ice complex and its proglacial lakes—ancestral Iroquois, Algonquin, and Champlain basins—framed by newly deglaciated river valleys.

The Great Lakes corridor, the St. Lawrence–Hudson axis, and emerging Atlantic forelands formed the core of early post-glacial forager landscapes. -

Gulf & Western North America stretched from the Gulf Coast and Southern Plains across the deserts and canyons of the Southwest to the California littoral and Channel Islands.

Its mosaic of pluvial lakes, estuaries, and upwelling-rich coasts provided a warm-water counterpoint to the glacial north.

Together these zones composed a continental hinge between Ice-Age Eurasia and the Americas—each subregion a stage in the story of human dispersal and adaptation to the extremes of a changing world.

Climate and Environmental Shifts

The period encompassed the height of the Last Glacial Maximum. Yet regional variation produced a continent of contrasts:

-

In the Northwest, severe cold and aridity dominated inland Beringia, though coastal polynyas and summer grasslands offered productivity.

-

In the Northeast, alternating Dansgaard–Oeschger warm pulses and Heinrich cold snaps drove cycles of ice advance and retreat, spawning huge meltwater floods and loess plains.

-

In the Gulf & Western corridor, cooler but relatively stable climates supported pluvial lake systems and broad river valleys; along California’s margin, coastal upwelling made the Pacific rim one of the richest marine environments on Earth.

Low sea levels united Alaska and Siberia, widened the Pacific and Gulf shelves, and created continental interiors laced with temporary lakes, dunes, and glacial outwash plains—landscapes of constant flux but enduring opportunity.

Lifeways and Settlement Patterns

Northern North America during this interval was a frontier of mobility—a patchwork of exploratory movements, seasonal circuits, and, by the end of the epoch, enduring forager traditions.

-

In the Northwest, big-game hunters pursued mammoth, bison, and horse across the Beringian grasslands. Seasonal camps clustered at river confluences and bluff edges, while coastal groups ventured onto land-fast ice and ice-edge polynyas for seals and seabirds.

These were small, mobile bands accustomed to long circuits between steppe and shore. -

In the Northeast, later arrivals followed the retreating ice margins into proglacial valleys. Fluted-point traditions reveal expert hunters tracking caribou, elk, and deer across freshly deglaciated terrain.

Camps on river terraces and kame plains served as transient bases for butchery and tool repair rather than long-term villages. -

In the Gulf & Western regions, climatic moderation and ecological diversity allowed sustained occupation. Coastal foragers exploited shellfish, fish, and marine mammals along the expanded California and Gulf shelves, while interior hunters roamed canyonlands and pluvial basins in pursuit of camelids, horses, and later deer and pronghorn.

Rockshelters and spring-fed oases formed the nuclei of repeated seasonal use.

Across all three subregions, subsistence strategies balanced large-game hunting, aquatic foraging, and strategic mobility—the adaptive triad that defined Ice-Age resilience.

Technology and Material Culture

From Beringia to the Gulf, technology reflected shared Upper Paleolithic roots tempered by local innovation.

-

Northwestern assemblages featured blade and microblade industries in high-quality chert and obsidian, with inset composite points, burins, and sewing needles for tailored skins.

-

Northeastern traditions emphasized fluted projectile points, prismatic blades, and scrapers crafted from long-distance lithic sources, signaling wide-ranging exchange and expertise in stone selection.

-

Gulf & Western toolkits relied on flake–blade technology, early hafting, fire use, and pigment processing, suited to mixed desert, canyon, and littoral ecologies.

Throughout the region, ochre pigments and personal ornaments (drilled teeth, shells, beads) reveal symbolic continuity with the larger circumpolar Upper Paleolithic world.

Movement and Interaction Corridors

Northern North America’s human geography was defined by corridors of ice, water, and stone:

-

The Beringian steppe and the Yukon–Mackenzie trench formed the first continental highway, linking Siberia to interior North America.

-

The ice-free Pacific coast—the embryonic “kelp highway”—offered a maritime alternative, dotted with refugia along Alaska’s and British Columbia’s fjorded shores.

-

As deglaciation advanced, the St. Lawrence, Great Lakes, and Mississippi basins became arteries of migration and trade.

-

Farther south, the Rio Grande–Gila–Colorado network and the Gulf estuaries tied the interior to marine resources.

Through these routes, populations spread, merged, and diverged, laying the demographic foundations of later Holocene cultural provinces.

Cultural and Symbolic Expressions

Symbolic life across Northern North America echoed Eurasian antecedents yet developed distinctive local signatures.

Ochre-stained hearths, portable ornaments, and structured camp layouts indicate social memory and ritual behavior.

In both Beringia and the Great Lakes heartland, burials with pigment and grave goods suggest shared beliefs in ancestral continuity.

These expressions, modest in scale yet rich in meaning, anchored social cohesion in landscapes that demanded both cooperation and constant movement.

Environmental Adaptation and Resilience

Resilience was achieved through mobility, diversification, and knowledge of seasonality:

-

Layered clothing, snow shelters, and fire technology extended human presence deep into subarctic zones.

-

In milder belts, foragers exploited estuaries, riverine wetlands, and pluvial lakes, moving along altitudinal and hydrological gradients.

-

Coastal populations learned to synchronize with marine cycles; interior hunters tracked herd migrations across vast steppes.

This adaptive plasticity allowed human groups to colonize environments ranging from glacial fjords to desert basins—a testament to the flexibility that made the Americas habitable at the height of global cold.

Transition Toward the Last Glacial Maximum

By 28,578 BCE, Northern North America stood at the threshold of transformation.

Ice sheets approached their greatest extent, closing interior corridors but leaving narrow coastal and riverine refuges.

Populations in Beringia maintained a tenuous bridge between continents, while others expanded southward along the Pacific and Gulf margins into unglaciated refugia.

The region thus embodied the Twelve Worlds principle: a set of distinct yet interdependent subregions—each self-contained, each connected through migration, exchange, and shared adaptation—that together forged the human foothold on a glacial continent.