Northern North America (28,577 – 7,822 BCE): …

Years: 28577BCE - 7822BCE

Northern North America (28,577 – 7,822 BCE): Upper Pleistocene II → Early Holocene — Deglaciation, Kelp Highways, and Pluvial Heartlands

Geographic & Environmental Context

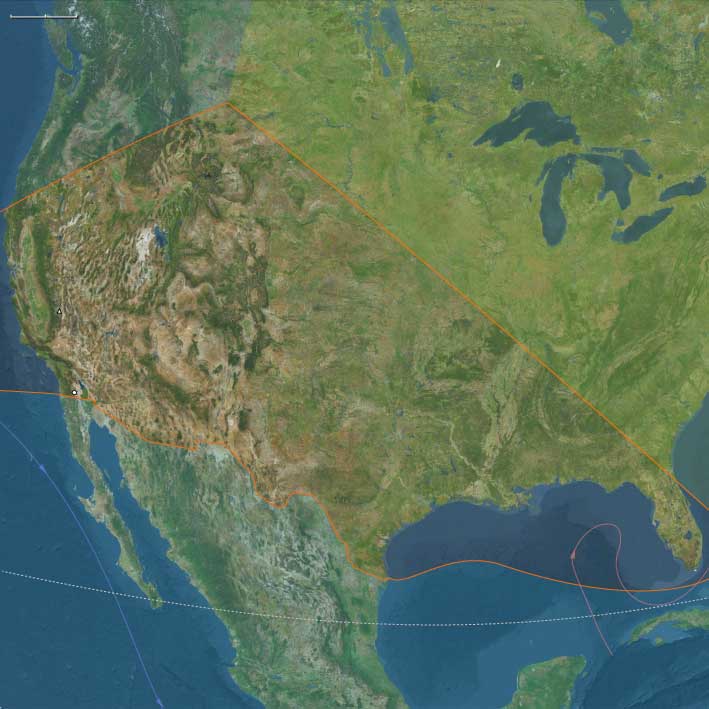

From the Bering Strait and Aleutians to the Gulf of Alaska, down the Inside Passage–Haida Gwaii–Vancouver Island chain and along the Klamath–Redwood coast, and across the continent through the Yukon–Fraser–Columbia–Mississippi drainages to the Great Lakes–St. Lawrence, Hudson Bay, and the Mid-Atlantic–New England shore, Northern North America took shape as ice withdrew and seas rose.

Three interlocking spheres structured lifeways:

-

Northwestern North America — The Cordilleran–Beringian gateway, with Brooks Range and North Slopetundras, Yukon–Kuskokwim and Copper–Cook Inlet basins, the Gulf of Alaska and Aleutian arcs, and the Southeast Alaska–Haida Gwaii–outer BC fjordlands. Late-opening ice-free corridors and a sheltering, resource-rich kelp-forest coast defined movement and subsistence.

-

Gulf & Western North America — The California Current coast (Channel Islands to Puget/Salish), the Lower Mississippi and Gulf Coast estuaries, the Southern Plains, Colorado Plateau, and the Great Basin of pluvial lakes. Here, estuary chains, canyon springs, and inland basins created a patchwork of productive niches.

-

Northeastern North America — The Chesapeake–Delaware–Hudson–Gulf of Maine margins, Great Lakes–Ohio–Mississippi valleys, Appalachian ridge-and-valley, Upper St. Lawrence–Quebec, and the Baffin–Labrador rim. As the Ancylus/Champlain seas waxed and waned and isostatic rebound re-shaped coastlines, mixed forest–water ecotones proliferated.

Across all three spheres, postglacial estuaries, high-latitude tundra–taiga mosaics, and greening loess plainscreated an integrated coast–river–lake system that drew people into longer stays at dependable water-edge nodes.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

-

Bølling–Allerød (c. 14.7–12.9 ka): Warmer, wetter conditions greened interior loess plains, invigorated riverine and lacustrine productivity, and stabilized nearshore kelp forests; small ice-free coastal pockets opened along the Gulf of Alaska and SE Alaska–BC fjords.

-

Younger Dryas (c. 12.9–11.7 ka): A sharp cold–dry pulse renewed steppe/tundra, pinched interior water sources, and funneled people to fjord mouths, estuaries, and spring-fed refugia where marine and riparian resources remained reliable.

-

Early Holocene (post-11.7 ka): Rapid warming and rising seas flooded outer shelves, forming the modern estuaries and sounds; oak–hazel–elm forests raced poleward; salmon-bearing rivers stabilized; Great Basinlakes still dotted the interior though retreating.

This cadence favored dual mobility—coast ↔ interior, lake ↔ plain—while encouraging semisedentary anchoring at rich aquatic nodes.

Subsistence & Settlement

A continent-spanning broad-spectrum foraging economy matured, increasingly underwritten by fisheries and wetland yields:

-

Northwestern Coast & Beringia: Foragers moved fjord by fjord along a “kelp highway,” harvesting rockfish, salmon, shellfish, sea urchins, waterfowl, and seals, with dugout/skin boats, tailored parkas, and sinew-sealed seams enabling year-round littoral rounds. Interior camps on river benches and rock shelters targeted caribou, elk, and whitefish/salmon at crossings; by the Early Holocene, weirs and fish traps appear, and stays on raised marine terraces lengthened toward semisedentism.

-

Gulf & Western Interior: Along the Lower Mississippi and Gulf estuaries, semirecurrent camps clustered on natural levees, working oyster bars, mullet/menhaden runs, and back-swamp fauna. On the California–Channel Islands and outer coast, dense shell-middens, canoe/raft use, and targeted seabird/sea-mammalharvests foreshadow later maritime societies. In the Great Basin and Southwest, shore camps on pluvial lakescaptured fish and waterfowl, while pronghorn and small-game drives, geophyte digging, and seed processing rounded out diets.

-

Northeast & Great Lakes: Estuary and bay-head hamlets on the Severn–Delaware–Hudson–Maine coasts built early shell heaps; interior Great Lakes–river communities fished salmonids and sturgeon, hunted deer and moose, and gathered hazelnut, oak mast, and berries. Camps were seasonal but repeatedly reoccupied on dune ridges and terrace knolls, laying down deep middens and cemeteries.

Across all zones, semisedentary seasonality—anchoring at rich nodes with radiating forays—became a hallmark of the period.

Technology & Material Culture

Light, adaptable, and increasingly specialized toolkits supported both mobility and storage:

-

Lithics: Persistent microblade industries in the NW; widespread backed bladelets, trapezes, and notched/side-notched points elsewhere.

-

Aquatic gear: Bone/antler harpoons (often toggling), gorges, barbed points; stake-weirs, woven fish baskets, and net floats/sinkers; dugouts and skin boats on protected waters.

-

Processing & containers: Grinding slabs and handstones for seeds/geophytes; drying racks and smokehouses for fish/meat; organic containers (bark, skin); early use of blubber oils for waterproofing gear.

-

Ornaments & pigments: Beads of shell, bone, jet/amber, and teeth; ochre widely used in body/ritual contexts; carved bone/antler animal motifs signal deepening predator–prey cosmologies.

Movement & Interaction Corridors

A web of redundant routes ensured resilience:

-

Coastal: stepwise Southeast Alaska–Haida Gwaii–Vancouver Island–Puget; Klamath–Channel Islands arcs; short-hop cabotage between estuaries.

-

Riverine: Yukon, Fraser, Columbia, Sacramento–San Joaquin, Mississippi–Ohio–Illinois, St. Lawrence—all served as driftways, trade channels, and seasonal migration guides.

-

Overland: Drakensberg-style highland corridors in the Rockies and Appalachians; portages binding watersheds; interior Great Plains and boreal routes linking basins.

These corridors moved not only people and tools but also dried fish, fat, hides, pigments, and ideas, knitting together far-flung bands.

Cultural & Symbolic Expressions

Symbolic life was entwined with water, animals, and place:

-

Rock art and pecked engravings mark canyon walls and coastal shelters; imagery of salmon, seals, caribou, bear, and watercraft points to a cosmology of reciprocity with “animal persons.”

-

Red-ochre burials with curated toolkits and ornaments cluster near estuaries, lake margins, and river terraces, fixing lineage rights to critical nodes.

-

Midden mounds and lacustrine deposits served as ceremonial foci and archives of feast and return, materializing ancestral claims over weirs, groves, and crossings.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

Forager strategies balanced anchoring with agility:

-

Coastal–interior duality ensured protein continuity through climatic pulses;

-

Storage of oils, dried fish/meat, and nuts underwrote winter and drought survival;

-

Fine-grained seasonal scheduling tracked flood pulses, salmon runs, waterfowl migrations, and mast years;

-

Territorial norms around weirs, springs, and beaches managed access and minimized conflict.

These practices allowed populations to ride out the Younger Dryas setback and capitalize on Early Holocene productivity.

Long-Term Significance

By 7,822 BCE, Northern North America had coalesced into a storage-rich, water-anchored forager world: salmon estuaries and kelp-forest coasts in the northwest, pluvial-lake and estuary chains across the west and Gulf, and forest–river–bay mosaics in the northeast.

This emergent system—portfolio subsistence, semi-sedentary nodes with radiating rounds, engineered fisheries and food storage, and ritualized tenure over key waters—formed the durable substrate from which later Northwest Coast maritime societies, Archaic mound-building traditions, and riverine trade networks would grow as the Holocene unfolded.