Northern North America (1252 – 1395 CE): …

Years: 1252 - 1395

Northern North America (1252 – 1395 CE): Salmon Chiefdoms, Iroquoian Ascendancy, and the Continental Exchange

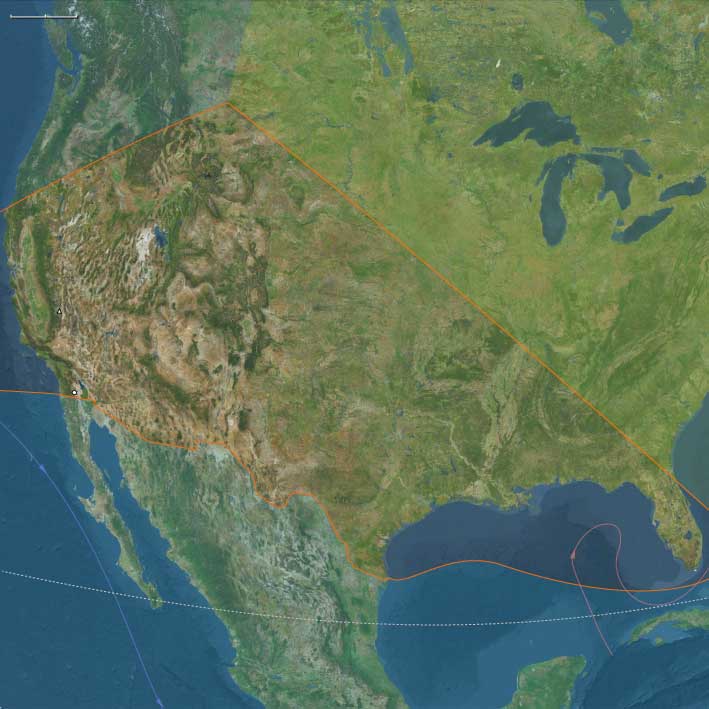

Across the northern half of the continent, from Alaska’s fjords to Florida’s mangroves, the centuries between 1252 and 1395 were marked by both consolidation and transformation. As the warmth of the Medieval era ebbed, cooler and stormier centuries tested the great riverine and coastal societies of North America—but they endured through ingenuity, mobility, and exchange. The result was a web of civilizations linked by trade in salmon, copper, shells, maize, and ideology, stretching from the Arctic whaling camps to the Mississippi mounds and the Californian shores.

Northwestern Shores and Salmon Kingdoms

Along the North Pacific Coast, maritime chiefdoms reached their peak. From the fjords of Southeast Alaska to the Salish Sea, ranked lineages of Tlingit, Haida, Tsimshian, Kwakwaka’wakw, and Coast Salish peoples controlled salmon rivers, tidal flats, and cedar forests. House-crests, totems, and potlatch feasts codified rights to resources, transforming stored salmon, seal oil, and copper ornaments into instruments of status and diplomacy. In the Gulf of Alaska and Aleutian Islands, the Unangan and Sugpiaq built skin-covered boats and toggling harpoons to hunt seals and whales, while Arctic Iñupiat communities of Thule descent perfected cooperative bowhead hunts along the frozen shore.

Inland, Dene (Athabaskan) peoples—Gwich’in, Kaska, Tahltan, and others—moved between river fisheries and caribou ranges. They exchanged native copper, obsidian, and hides for coastal eulachon oil carried over mountain “grease trails.” Together, these coastal and interior systems formed a salmon-and-grease economy that tied the Yukon to Puget Sound and proved resilient under the first chills of the Little Ice Age.

Eastern Forests and Great Lakes Peoples

Far across the continent, the riverine chiefdoms of the Mississippi Valley waned as new polities rose. The great city of Cahokia, weakened by floods, droughts, and internal stress, was abandoned by the mid-fourteenth century. Yet its mound-building legacy endured in the Lower Mississippi, where Natchez, Plaquemine, and Etowah peoples sustained maize agriculture and ritual kingship. Farther north, around the Great Lakes and the St. Lawrence, Iroquoian and Algonquian villages flourished.

The Iroquoian towns of Ontario and New York, enclosed by palisades and defined by longhouse clans, organized around matrilineal lineages that prefigured later confederacies. Their maize-beans-squash agriculture supported dense settlements; hunting and fishing supplied surpluses for diplomacy and war. To their north and east, Algonquian nations combined farming, fishing, and forest foraging in a flexible cycle that ensured survival through climatic fluctuation.

Meanwhile, on the continent’s frozen edge, the Inuit (Thule) expanded across the Arctic archipelago and into Greenland, displacing the Norse settlers whose farms succumbed to failing pastures and isolation. The last Norse church bells faded in the late fourteenth century as Inuit umiaks and sled teams dominated the northern seas.

Western Deserts, Plateaus, and Pacific Rim

Southward and inland, in the mountains and deserts of the West, the onset of aridity reshaped communities. In the Southwest, the Ancestral Puebloans entered the Pueblo IV era, gathering into larger towns on the Zuni and Hopimesas and along the Rio Grande. Painted kivas and katsina ceremonies unified villages under shared ritual calendars. In the Hohokam lowlands of the Salt and Gila rivers, extensive irrigation networks continued, though salinization and drought forced migration and reorganization.

Across the Great Basin, small foraging bands expanded pine-nut and seed use; in the California valleys and coasts, Chumash, Miwok, and Ohlone peoples created rich economies based on acorns, shell-bead currency, and ocean trade. Chumash plank canoes (tomols) connected the Channel Islands to mainland markets, exchanging shell beads, fish, and pigments. These Pacific chiefdoms paralleled their northern neighbors in complexity, forging an unbroken coastal network of ritual exchange and seaborne commerce.

Southern Plains and Gulf Chiefdoms

Eastward, the Lower Mississippi and Gulf Coast retained a tapestry of mound-town chiefdoms and coastal polities. At Spiro (Oklahoma) and Etowah (Georgia), elaborate copper plates, shell gorgets, and birdman effigies reflected the ceremonial universe of the Southeastern Ceremonial Complex. Along the Gulf, the Calusa and other coastal fisher-chiefs ruled estuaries from fortified towns, wielding sacred bundles and tribute networks sustained by marine abundance.

In the Texas–Oklahoma plains, bison hunting intensified, while maize farming along rivers provided stability. Across the Southwest–Plains transition, trade carried turquoise, bison robes, shells, and macaws in circuits reaching from Mesoamerica to the Mississippi.

Economy, Exchange, and Technology

Northern North America thrived on environmental variety.

-

Coasts and rivers: salmon, cod, and eulachon oil in the Pacific; herring and shellfish in the Atlantic.

-

Forests: maize, beans, acorns, and wild rice anchored diverse agricultures.

-

Mountains and plains: obsidian, copper, and bison products supplied continental trade.

Canoes—dugout, plank, or birchbark—were universal instruments of movement; so were snowshoes, sleds, and storage pits. Long-distance corridors connected every major culture zone: Inside Passage fleets linked Alaska to Puget Sound; the Mississippi and Missouri funneled goods north and south; Great Lakes waterways met Hudson Bay routes; and overland paths tied Puebloan mesas to Gulf chiefdoms and the Pacific coast.

Belief and Symbolism

Ritual life revolved around animals, ancestors, and celestial order.

-

North Pacific lineages carved crests and totems affirming ties to salmon and bear spirits; first-salmon ceremonies renewed ecological balance.

-

Mississippian societies celebrated fertility and war through birdman imagery, mound rituals, and sacred fire.

-

Pueblo kivas sustained cyclical dance traditions linking earth and sky; Chumash voyagers mapped constellations into their maritime cosmology.

-

Iroquoian longhouse rituals honored Sky Woman and the Three Sisters of agriculture; Algonquian vision quests sought harmony with guardian spirits.

-

In the Arctic, whale and seal ceremonies reaffirmed reciprocity between human and animal worlds.

Everywhere, spiritual practice reinforced environmental stewardship and social solidarity.

Adaptation and Resilience

The onset of cooler climates demanded flexibility. Coastal storage economies—smoked fish, rendered grease, dried acorns—bridged lean seasons. River and lake villages relocated when floods or silt clogged channels. Irrigation, mound renewal, and ritual redistribution managed ecological stress. Mobility and diplomacy mitigated conflict: alliances forged through feasts, intermarriage, and ceremonial trade allowed populations to recover from famine or warfare.

Despite regional collapse—Cahokia in the Mississippi valley, Norse Greenland in the Arctic—neighboring societies restructured rather than declined. Diversity of subsistence, surplus storage, and shared ideology ensured continuity through climate shock and disease.

Long-Term Significance

By 1395 CE, Northern North America was a continent of mature, interconnected societies.

The North Pacific chiefdoms refined hierarchical systems based on salmon and cedar wealth; the Thule-derived Inuit achieved their greatest whaling expansion before later cooling; and Dene traders spanned interior forests with copper and fur exchange.

In the east, Iroquoian and Algonquian peoples dominated the Great Lakes and St. Lawrence, heirs to the Mississippian legacy; Inuit hunters replaced the Norse in Greenland’s fjords.

In the south and west, Pueblo IV, Chumash, and Gulf Coast societies preserved complex ritual economies tied to broader continental networks.

Together these worlds formed a continuous northern commonwealth—one bound by waterways, storied landscapes, and ecological intelligence. Through adaptability, mobility, and trade, the peoples of Northern North America sustained cultural florescence on the eve of the colder centuries to come.

Groups

- Kwakwakaʼwakw

- Coast Salish

- Haida people

- Tlingit people

- Athabaskans, or Dene, peoples

- Nuu-chah-nulth people (Amerind tribe; also formerly referred to as the Nootka, Nutka, Aht, Nuuchahnulth)

- Klamath (Amerind tribe)

- Tsimshian

- Eyak

- Aleutian Tradition

- Tahltan

- Alutiiq (Eskimo tribe)

- Aleut people

- Inupiat

- Kaska Dena

- Dakelh

- Gwichʼin

- Thule people

- Thule Tradition, Classic Thule

Commodoties

- Fish and game

- Weapons

- Hides and feathers

- Glass

- Colorants

- Oils, gums, resins, and waxes

- Strategic metals

Subjects

- Commerce

- Architecture

- Watercraft

- Sculpture

- Painting and Drawing

- Environment

- Decorative arts

- Mayhem

- Government

- Custom and Law

- Technology