Northern North America (1108 – 1251 CE): …

Years: 1108 - 1251

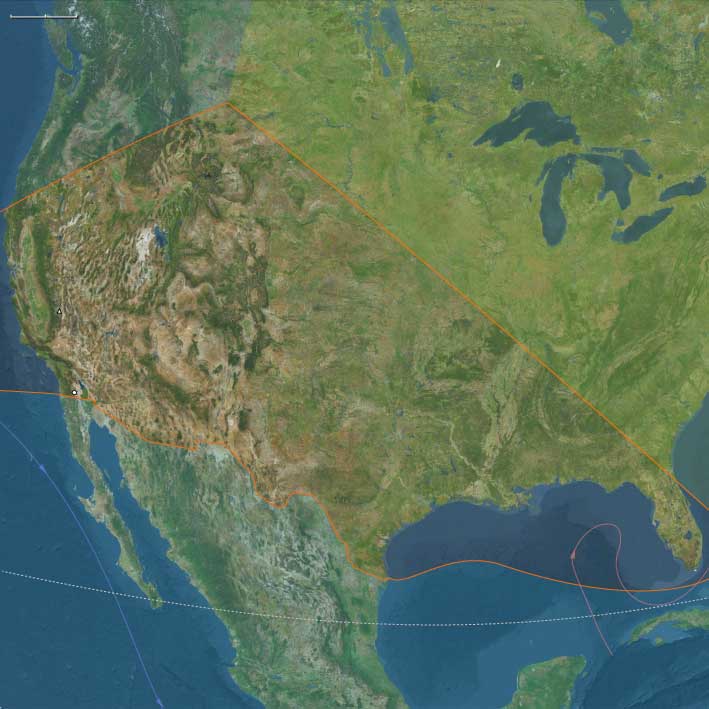

Northern North America (1108 – 1251 CE): Mound Empires, Maritime Chiefdoms, and Arctic Frontiers

Between 1108 and 1251 CE, the northern half of North America witnessed extraordinary cultural florescence.

Along the Mississippi and Gulf coasts, mound-building chiefdoms reached their urban zenith.

Across the Pacific Northwest, cedar-plank towns and potlatch chiefdoms thrived on salmon surpluses.

In the northeast, the great city of Cahokia towered over the interior plains while Iroquoian and Algonquian farmers expanded across the forests.

Farther north and west, Norse settlers in Greenland and Inuit hunters in the Arctic maintained one of the world’s oldest transpolar connections.

The entire continent—linked by rivers, trade routes, and seaways—became a web of powerful regional civilizations, each adapting to its unique environment while exchanging goods, symbols, and ideas.

Geographic and Environmental Context

Northern North America encompassed the Pacific rainforests, the Great Plains and Mississippi basin, the Appalachian and Laurentian uplands, and the Arctic–subarctic tundra.

-

The Pacific coast was a land of fjords, cedar forests, and salmon-rich rivers.

-

The Great Lakes and Mississippi plains formed an agricultural heartland sustained by maize cultivation.

-

The Gulf and Southwest zones supported irrigated farming and trade networks.

-

The Arctic north and Greenland lay within zones of fishing, hunting, and ice navigation.

This ecological variety produced some of the richest subsistence systems in the pre-Columbian world, from intensive agriculture to marine economies.

Climate and Environmental Shifts

The Medieval Warm Period (c. 950–1250) brought longer growing seasons, higher yields, and stable fisheries.

-

Cahokia’s floodplain produced maize surpluses supporting large urban populations.

-

Northwest Coast rivers experienced peak salmon runs, anchoring food wealth and social stratification.

-

The Southwest and Great Basin faced early droughts after 1200, pressuring Puebloan migrations.

-

Greenland’s Norse colonies prospered marginally, grazing livestock and exporting walrus ivory.

Milder conditions stimulated demographic growth across nearly every ecological zone.

Societies and Political Developments

Pacific Northwest Chiefdoms:

Tlingit, Haida, Tsimshian, Kwakwaka’wakw, and Coast Salish societies developed ranked, hereditary systems rooted in salmon control and trade monopolies.

Villages of plank houses lined fjords; cedar canoes carried goods and warriors along the Inside Passage.

Potlatch ceremonies and monumental totems dramatized wealth and ancestry.

In Alaska, Yup’ik and Inupiat communities combined maritime hunting and reindeer herding, sustaining life along the tundra coasts.

Interior and Plateau Peoples:

Nlaka’pamux, Ktunaxa, and Dene (Athabaskan) groups inhabited interior valleys, mixing foraging and horticulture.

Southward Dene migrations foreshadowed the later rise of Apache and Navajo peoples.

The Mississippian Mound World:

At its height (~1200 CE), Cahokia near modern St. Louis supported over 20,000 inhabitants, dominated by Monk’s Mound and vast plazas aligned to celestial cycles.

Its influence radiated through networks linking Etowah, Moundville, Spiro, and Natchez.

Elites commanded maize tribute, ritual authority, and long-distance trade in copper, shell, and stone.

Farther south, Gulf chiefdoms maintained continuity after Cahokia’s decline.

Puebloan and Western Cultures:

The Ancestral Puebloans (Mesa Verde, Chaco Canyon) reorganized into larger mesa-top and cliff settlements as drought stressed irrigation networks.

Hohokam farmers maintained extensive canal systems along the Salt and Gila rivers, cultivating cotton and maize despite increasing salinity.

On the Pacific coast of California, Chumash and Tongva chiefdoms expanded canoe trade using shell-bead currencies that circulated for hundreds of miles.

Eastern Woodlands and Great Lakes:

In the northeast, Iroquoian and Algonquian societies flourished.

Iroquoian-speaking groups in Ontario and New York built longhouse villages and palisaded towns, experimenting with confederacies that would later coalesce into the Haudenosaunee League.

Algonquians along the coasts and rivers practiced mixed farming, fishing, and foraging, forming dynamic regional alliances.

Arctic and North Atlantic Frontiers:

Thule Inuit expanded eastward across the Canadian Arctic, mastering seal and whale hunting, sled technology, and snowhouse construction.

Across the sea, Norse Greenlanders built churches, exported ivory, and traded intermittently with Europe via Iceland and Norway.

The Bering Strait maintained trans-Arctic contact between Chukchi and Alaskan Inuit peoples—one of humanity’s oldest enduring links.

Economy and Trade

Agriculture and Food Systems:

-

Mississippi–Ohio valleys: intensive maize agriculture and fish weirs supported dense populations.

-

Great Lakes and Northeast: maize-bean-squash “Three Sisters” cultivation spread.

-

Pacific Northwest: salmon, halibut, and shellfish formed the subsistence core.

-

California: acorn and seed processing underpinned regional stability.

-

Arctic: seal, walrus, and whale provided meat, oil, and tools.

Trade Networks:

-

Cahokian exchange moved copper from the Great Lakes, shells from the Gulf, and obsidian from the Rockies.

-

Northwest Coast trade linked coastal and interior peoples through copper, hides, and slaves.

-

California–Great Basin routes exchanged obsidian, salt, and shell beads.

-

Arctic exchanges carried ivory, furs, and metal objects between Inuit, Norse, and Siberian groups.

Continental trade created overlapping economic spheres connected by rivers, trails, and maritime corridors.

Belief and Symbolism

-

Mississippian ceremonialism: cosmologies of upper and lower worlds, fertility, and warfare expressed through mound alignments and copper iconography.

-

Northwest Coast mythology: clan totems, animal transformations, and ancestral spirits materialized in carvings and masks.

-

Puebloan religion: kiva rituals and katsina cults linked agriculture to celestial order.

-

Iroquoian cosmology: stories of Sky Woman and the Earth-Diver mirrored social harmony within the longhouse.

-

Inuit and Yup’ik spirituality: maintained reciprocity with sea and ice spirits through hunting rites.

-

Norse Christianity: churches and burials in Greenland reflected both European piety and Arctic endurance.

In every region, spiritual life united ecology, kinship, and cosmic order.

Subsistence and Technology

-

Cedar woodworking supported monumental architecture and seafaring in the Northwest.

-

Fish traps, weirs, and smokehouses maximized salmon preservation.

-

Mound construction required organized labor and astronomical precision.

-

Hohokam canal engineering extended irrigation over miles of desert terrain.

-

Shell-bead currency standardized exchange in California and along the Pacific.

-

Kayaks, umiaks, and sleds enabled Arctic mobility; iron and ivory tools diffused through Norse-Inuit contact.

Technological ingenuity adapted each environment into a landscape of abundance.

Movement and Interaction Corridors

-

Inside Passage: Alaska ⇄ British Columbia ⇄ Puget Sound, uniting maritime chiefdoms.

-

Mississippi–Ohio system: Cahokia ⇄ Etowah ⇄ Gulf coast, artery of mound culture.

-

Rocky Mountain trails: linked Puebloan, Plains, and Mississippian traders.

-

Great Lakes–St. Lawrence routes: connected Iroquoian farmers to Atlantic trade.

-

Gulf Stream crossings: carried Norse ships from Greenland to Iceland, and Inuit hunters across Baffin Bay.

These corridors wove a continental web of exchange and symbolic contact from the Arctic to the Gulf.

Adaptation and Resilience

-

Agricultural diversification and surplus storage sustained Mississippian and Iroquoian societies.

-

Salmon abundance and maritime trade stabilized Northwest chiefdoms.

-

Irrigation, terrace farming, and ritual cooperation buffered Pueblo communities against drought.

-

Mobility and ecological knowledge allowed Inuit, Yup’ik, and Dene survival under Arctic conditions.

-

Ritual redistribution (potlatch, mound feasts) maintained social cohesion during scarcity.

Resilience lay in flexibility—combining surplus economies with spiritual systems that honored ecological balance.

Long-Term Significance

By 1251 CE, Northern North America was a mosaic of civilizations, each reflecting mastery of its environment:

-

Cahokia stood as the continent’s largest pre-Columbian city, symbol of agrarian urbanism.

-

Northwest Coast chiefdoms flourished in wealth, art, and ceremonial complexity.

-

Pueblo and Hohokam towns persisted as centers of irrigation and ritual innovation.

-

Iroquoian and Algonquian farmers expanded their forest domains.

-

Inuit hunters and Norse settlers maintained the northernmost economies on Earth.

Together they composed an intricate continental system—distinct yet interconnected—whose cultural and ecological foundations would endure long after 1251, even as the medieval world beyond the seas moved toward global convergence.

Groups

- Kwakwakaʼwakw

- Coast Salish

- Haida people

- Tlingit people

- Athabaskans, or Dene, peoples

- Nuu-chah-nulth people (Amerind tribe; also formerly referred to as the Nootka, Nutka, Aht, Nuuchahnulth)

- Klamath (Amerind tribe)

- Tsimshian

- Eyak

- Aleutian Tradition

- Thule Tradition, Punuk and Birnirk Stages

- Inupiat

- Inuit

Topics

Commodoties

- Fish and game

- Weapons

- Hides and feathers

- Colorants

- Glass

- Oils, gums, resins, and waxes

- Grains and produce

- Strategic metals

- Slaves

- Lumber

Subjects

- Commerce

- Watercraft

- Sculpture

- Painting and Drawing

- Environment

- Decorative arts

- Faith

- Government

- Custom and Law

- Technology