The West Indies (49,293–28,578 BCE): Upper Pleistocene …

Years: 49293BCE - 28578BCE

The West Indies (49,293–28,578 BCE): Upper Pleistocene I — Exposed Banks, Reef Arcs, and Island Worlds Without People

Geographic and Environmental Context

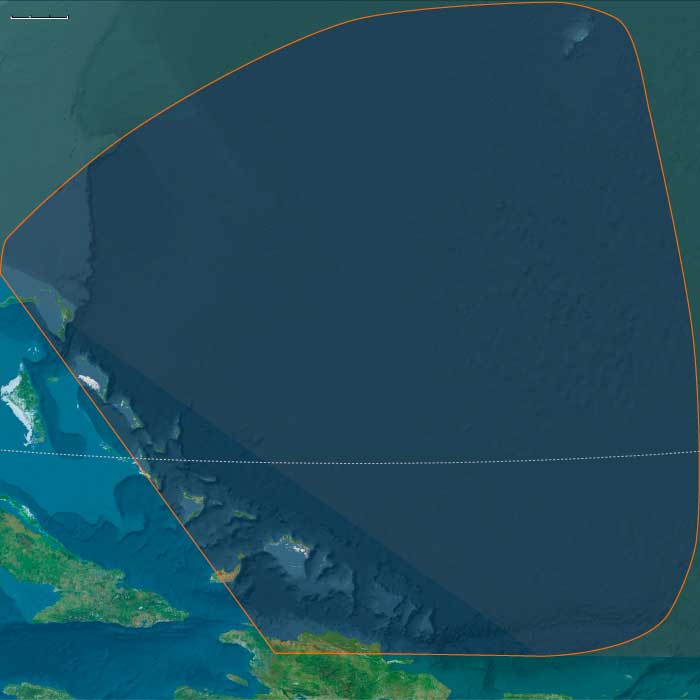

During the late Pleistocene, the West Indian archipelagos—stretching from the Bahama banks to Trinidad—were vast, emergent shelves divided into three natural subregions that would later become cultural zones: the Northern, Eastern, and Western West Indies.

-

The Northern West Indies comprised the Bahamas and Turks & Caicos banks and the northern coast of Hispaniola.

Sea levels ~100 m lower than today fused many of the present islands into broad limestone plains dotted with sinkholes and dune fields. The Cibao Valley and the Massif du Nord of Hispaniola formed the rugged southern margin of this shelf sea. -

The Eastern West Indies traced a long volcanic and carbonate arc from Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands through the Lesser Antilles to Trinidad & Tobago, where the chain met the South American shelf.

Active volcanoes alternated with uplifted reef terraces and deep inter-island channels shaped by the northeast trades. -

The Western West Indies included Cuba, Jamaica, the Cayman Ridge, and western Hispaniola, flanked by the deep Cayman Trench and the Windward Passage.

Here, broad banks and narrow straits created a labyrinth of shelves, slopes, and enclosed lagoons fringed by coral and seagrass ecosystems.

These three subregions were already differentiated by geology and oceanography: the Northern banks were broad, flat, and porous; the Eastern arc steep and windward; the Western ridge mountainous and trench-bound. Together they formed the tropical hinge between the Atlantic and Caribbean basins—an archipelago before humanity, alive only with reefs, birds, and tides.

Climate and Environmental Shifts

The interval coincided with the approach to the Last Glacial Maximum, producing climatic contrasts across latitude and elevation:

-

Sea level fall of 90–110 m exposed vast carbonate platforms in the Bahamas and Caicos and broadened coastal plains around Cuba and Hispaniola.

-

Trade winds intensified as global temperature gradients sharpened, driving upwelling and enhancing nutrient flows along windward coasts.

-

Cooler sea-surface temperatures slowed coral accretion but favored calcareous algae, sponges, and mollusks, maintaining high marine productivity.

-

Periodic northers and dry seasons reduced rainfall, particularly over the northern and western islands, while volcanic highlands in the east retained moist forests and orographic rainfall.

The result was a gradient from arid limestone plains in the north to humid volcanic slopes in the east, already anticipating the ecological zones that would later support very different island societies.

Biotic Assemblages and Ecological Structure

With no humans yet present, the Pleistocene West Indies were laboratories of insular evolution:

-

Seabirds dominated: vast rookeries of boobies, frigatebirds, shearwaters, and petrels nested on cliffs and dunes from the Bahamas to the Grenadines.

-

Reptiles and amphibians were diverse, including large lizards and ground-dwelling tortoises on the larger banks.

-

Mammals were limited to endemic rodents and small insectivores; ground sloths and monkeys persisted on Cuba and Hispaniola into later millennia.

-

Marine ecosystems—reef flats, turtle-nesting beaches, mangrove-lined lagoons—functioned at full productivity, unaltered by hunting or fire.

-

Beneath the islands, freshwater lenses formed within porous limestones, supporting vegetation pockets and stabilizing the water table.

These pristine ecologies, organized by rainfall and ocean currents rather than human movement, set the template for all later biological and cultural differentiation in the Caribbean.

Movement and Interaction Corridors

Although uninhabited, the region was threaded by powerful oceanic highways that would later shape both migration and commerce:

-

The North Equatorial Current and its offshoot, the Florida Current, swept westward across the Lesser Antilles and northward through the Bahamas toward the Gulf Stream.

-

Countercurrents and eddies along the Caribbean side of the arc distributed larvae, seeds, and drifting vegetation between islands, knitting their ecosystems together.

-

These same pathways would eventually become the maritime corridors of human voyaging; in this epoch, they served only seabirds and sea turtles, tracing the routes that future canoes would follow.

Cultural and Symbolic Dimensions

No human symbolic system had yet entered this landscape, yet the environment itself encoded rhythms and structures that later peoples would mythologize: the circularity of atolls, the seasonal pulse of trade winds, the nesting cycles of seabirds, the periodic flooding and drying of lagoons.

These were the physical archetypes of later Caribbean cosmologies—worlds of tide and return, absence and reemergence.

Environmental Adaptation and Resilience

In biological terms, the archipelago functioned as a self-balancing triad:

-

Northern carbonate banks acted as vast nurseries for marine life, their freshwater lenses and seagrass meadows stabilizing regional nutrient budgets.

-

Eastern volcanic islands provided vertical zonation—reef, mangrove, forest—that buffered storms and erosion.

-

Western highlands generated sediment and nutrients feeding neighboring shelves.

Interconnected by wind and current, these systems maintained equilibrium without external disturbance. Each island was autonomous yet ecologically interdependent—an early analogue of the inter-island diversity that would later underpin cultural resilience in the peopled Caribbean.

Transition Toward the Last Glacial Maximum

By 28,578 BCE, the West Indies were an archipelago of abundance awaiting discovery.

Emergent banks and volcanic ridges, swept by steady trades, supported some of the most productive reef and seabird ecosystems on Earth.

No human footprints yet marked their dunes, but the stage was set: broad shelves for future navigation, fertile soils for cultivation, and ecological gradients for diversification.

In this epoch, the Caribbean existed as a network of natural worlds, poised—like the other realms of The Twelve Worlds—to become human worlds when the seas rose again.