The West Indies (4,365 – 2,638 BCE): …

Years: 4365BCE - 2638BCE

The West Indies (4,365 – 2,638 BCE): Late Holocene — Islands in Formation and Pathways of Arrival

Geographic & Environmental Context

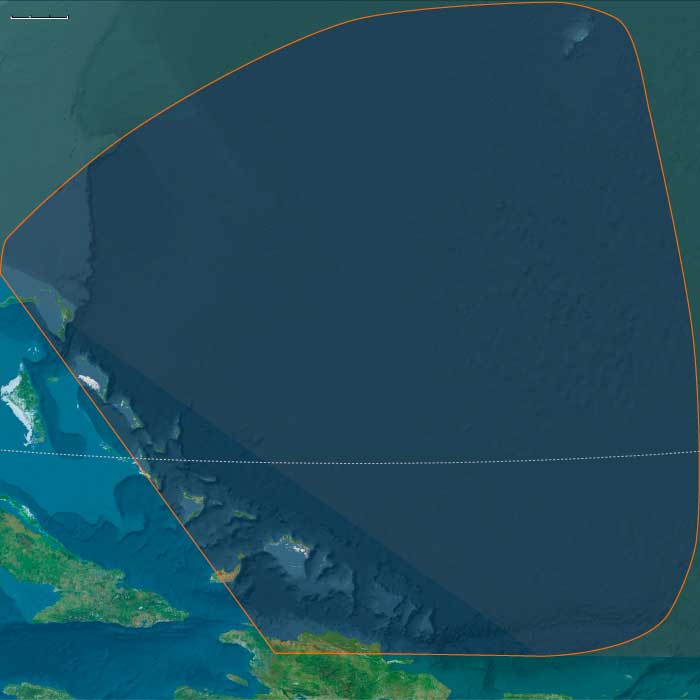

The West Indies—spanning the arc of islands between the Gulf of Mexico and the Atlantic Ocean—was, in this epoch, a world of reefs, banks, and volcanic ridges still stabilizing after the final postglacial sea-level rise. The region extended from the Bahamas and Turks & Caicos through the Greater and Lesser Antilles to Trinidad & Tobago and the coastal shelves of northern South America.

Shallow carbonate platforms in the north (Bahamas, Caicos, northern Hispaniola) contrasted with the high volcanic and limestone islands of the east (Puerto Rico, the Virgin Islands, the Leewards, and Windwards) and the mangrove-fringed deltas of the southern approaches. Each zone offered its own ecological portfolio—shellfish banks, fertile alluvial fans, and forested uplands—linked by predictable trade-wind and current corridors.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

The regional climate was warm, humid, and increasingly seasonal, with modest drying between 3500 and 3000 BCE. Sea levels stabilized close to modern heights, coral reefs flourished, and near-shore lagoons accumulated thick mangrove and shell sediments. Storm frequency increased slightly late in the epoch, but the long hurricane-free intervals allowed reef and beach regeneration. Rain-shadow valleys on larger islands such as Hispaniola and Puerto Rico promoted early dry-farming niches amid overall tropical abundance.

Subsistence & Settlement

For much of this epoch, island societies remained Archaic forager–fishers, their camps strung along bays and river mouths. Coastal peoples gathered shellfish, netted reef fish, and hunted hutia, iguana, and seabirds; in fertile interior valleys they collected palms, root crops, and wild fruit.

In the east, however, the first Saladoid horticulturalists from the Orinoco basin began to expand northward late in the period (after ~3000 BCE). Their cassava gardens and red-slipped ceramics spread through Trinidad & Tobago and the Lesser Antilles, while northern Hispaniola and the Bahamian banks remained preceramic. Thus, by the close of the epoch, the archipelago exhibited a cultural gradient—foragers and shell-midden communities in the north and west, horticultural pioneers in the east and south.

Technology & Material Culture

Preceramic technologies persisted across most islands: flake-stone tools, shell adzes, and bone points crafted for woodworking and fishing. In the southeastern chain, ceramic and weaving traditions appeared with incoming Saladoid groups—red-slipped, painted pottery, cassava griddles, spindle whorls, and finely carved stone celts. Canoe technology advanced everywhere: light dugouts and lashed-plank variants capable of inter-island travel in trade-wind intervals. Ornaments of shell, coral, and early copper beads reached select islands through down-the-line exchange from South American coasts.

Movement & Interaction Corridors

The sea was the connective tissue of West Indian life.

-

Northern lanes: through the Bahamas–Turks & Caicos–Hispaniola passages, seasonal canoe travel linked bank fisheries and shell-exchange networks.

-

Eastern corridors: the Orinoco–Trinidad–Windwards–Leewards–Puerto Rico chain carried Saladoid horticulturalists, ceramics, and crops northward.

-

Western approaches: currents along the Yucatán–Cuba–Hispaniola rim moved lithic materials and ritual shells between mainland and islands.

These pathways established the foundations for the later pan-Caribbean canoe economies that would tie every island to the continental margins.

Belief & Symbolism

Spiritual expression drew on ancestral ties to land and sea. Shell middens served as both larders and ritual monuments; burials within or beside them linked families to specific beaches and lagoons. In the eastern islands, ancestor house-shrines and feasting plazas emerged with the Saladoid horizon, marking a transition toward horticultural ritual economies. Rock engravings and painted stones—depicting humans, fish, and spiral motifs—evoked continuity between ocean currents and kin lines.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

Islanders lived by redundancy and mobility. Diverse food webs—reef, river, and forest—buffered cyclone damage. In the north, foragers rotated among cays and inland refugia; in the south and east, cultivators paired cassava plots with coastal fisheries to offset drought and storm loss. Storage of dried fish and shell meat, and the maintenance of canoe alliances across islands, provided social insurance against local failures.

Long-Term Significance

By 2,638 BCE, the West Indies had become a fully occupied maritime world, though still divided between forager heartlands and nascent horticultural colonies. Stable seas, flourishing reefs, and well-mapped canoe routes created a physical and cultural infrastructure that later Ceramic-Age societies would inherit and expand. The region’s enduring pattern—ecological diversity bound by mobility and ritual exchange—was already in place, preparing the islands for the flowering of Saladoid and later Arawakan civilizations that would knit the Caribbean into one of the ancient world’s most connected archipelagos.