West Indies (28,577 – 7,822 BCE): Upper …

Years: 28577BCE - 7822BCE

West Indies (28,577 – 7,822 BCE): Upper Pleistocene II → Early Holocene — Deglacial Shores, Mangrove Margins, and the First Island Stopovers

Geographic & Environmental Context

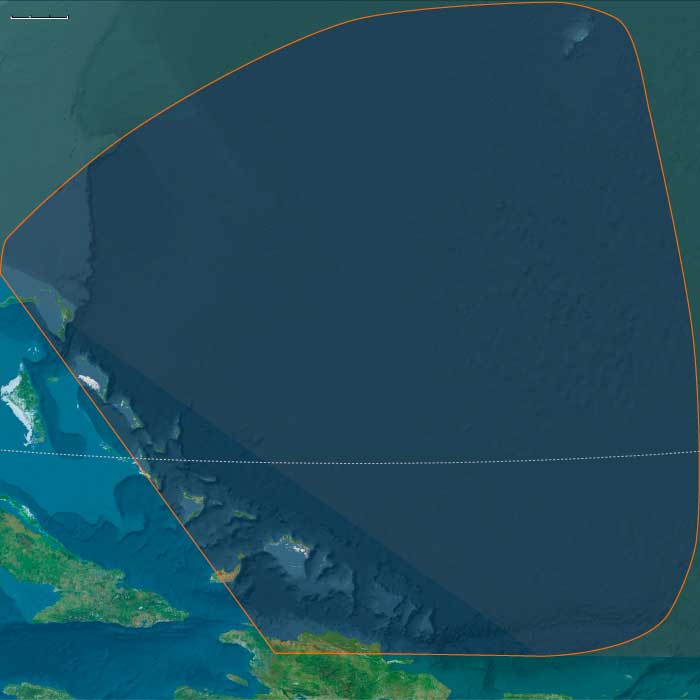

Spanning the Lucayan (Outer Bahamas) and Turks & Caicos banks, the Greater Antillean north coast (north Haiti’s Cap-Haïtien–Massif du Nord and the Cibao–Puerto Plata–Santiago corridor), the Puerto Rico–Virgin arc, the Lesser Antilles (Anguilla → Aruba), and Trinidad & Tobago at the Orinoco gate, the West Indies entered the Early Holocene as a necklace of rising reefs and widening lagoons.

As postglacial seas climbed ~60–80 m toward near-modern levels, exposed carbonate benches on the Bahama and Caicos platforms flooded into back-reef lagoons cut by new tidal passes; mangrove skirts thickened on leeward rims. Along northern Hispaniola, faulted ranges (Massif du Nord) shed sediments into incising Cibao rivers, building fertile fans against an enlarging shelf.

Across the eastern (Hispaniola–Puerto Rico–Lesser Antilles) and western (Cuba–Jamaica–Caymans–Gonâve) arcs, rocky promontories framed new embayments, while Trinidad & Tobago stood as the western hinge between island and continent. The Bahama–Caicos platforms remained vast, low, and storm-swept—physically inviting but thin-soiled and freshwater-poor.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

-

Bølling–Allerød (c. 14.7–12.9 ka): Regional seas warmed and coasts moistened; coral growth accelerated, reef flats aggraded toward sea level; mangroves colonized freshly flooded margins.

-

Younger Dryas (c. 12.9–11.7 ka): A short, cool–dry reversal lowered effective moisture and tempered reef accretion; dunes reactivated and lagoons periodically breached under stronger storms.

-

Early Holocene (post-11.7 ka): Monsoonal stability returned; trade-wind regimes regularized swell and rainfall; back-reef and mangrove systems stabilized, setting the physical template for later settlement.

Subsistence & Settlement

Occupation was sparse and episodic, with strongest signals at north-coast Hispaniola and Trinidad & Tobago; most outer banks and smaller islands (e.g., Turks & Caicos, Bahamas, many Lesser Antilles) show, at most, transient landfalls without durable villages.

-

Northern West Indies (Lucayan–Turks & Caicos–north Hispaniola):

• Hispaniola (north coast/Cibao): Preceramic Archaic foragers likely established semi-recurrent river-mouth camps, exploiting sturgeon-like fishes, reef and lagoon fish, mollusks, waterfowl, and deer/boar/ibex analogues in nearby foothills; shell scatters and simple hearths hint at feasting episodes.

• Bahamas & Turks/ Caicos: Cays and bank edges served as canoe stops and opportunistic foraging grounds (conch, turtles, seabirds); freshwater scarcity and storm-prone strandplains precluded stable occupation. -

Eastern West Indies (Hispaniola E., Puerto Rico, Virgin & Lesser Antilles, Trinidad & Tobago):

Seasonal shore stations formed at lagoon mouths and coves, especially where mangrove channels and fringe reefs concentrated resources. Trinidad & Tobago, tight to the Orinoco outflow and rich in estuarine fish, manatees, and turtles, were probable gateway nodes for ephemeral camps and knowledge transfer between mainland and islands. -

Western West Indies (Cuba–Jamaica–Caymans–W. Hispaniola):

Deglacial pass formation (e.g., Windward Passage, Jamaica Channel) created short-hop routes. Forager groups from the Greater Antilles likely made intermittent use of north-Cuba and Tortuga–Gonâve shorelines for marine harvests and lithic forays, leaving light, discontinuous scatters rather than permanent villages.

Technology & Material Culture

A preceramic, highly mobile toolkit prevailed:

-

Flaked stone: simple cores, expedient flakes, backed bladelets, scrapers for butchery and wood-working.

-

Bone tools: points, gorges, barbs for fish and turtle capture; awls/needles for skin and cordage work.

-

Watercraft: rafts and early dugout/dug-plank craft inferred from cross-channel movements and bank-edge stopovers.

-

Ornaments: shell beads and drilled teeth appear in coastal contexts; ochre used in body/ritual marking.

Movement & Interaction Corridors

The archipelago functioned as a stepping-stone seaway:

-

Hispaniola’s north coast as a launch/landfall interface with protected inlets and nearby freshwater.

-

Turks & Caicos and Bahama banks as seasonal corridors, utilized in calm-season windows, but largely uninhabited.

-

Orinoco–Trinidad–Lesser Antilles as a western Atlantic gateway, enabling episodic east–west drift and directed canoeing.

-

Windward Passage / Jamaica Channel as tentative links into western arcs (Cuba–Jamaica–Caymans), primarily for opportunistic forays.

Cultural & Symbolic Expressions

Where occupation occurred, waterfront places became mnemonic anchors:

-

Shell accumulations mark communal harvests and feasts at river mouths and coves, inscribing early claims to landing places.

-

Simple ornaments in coastal sites imply emergent identities and ties across shores.

-

In the absence of sustained settlement on the banks and many outer isles, natural rhythms—turtle crawls, seabird rookeries, seasonal fish runs—formed the ‘calendar’ of place.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

Foragers balanced littoral and riverine portfolios to ride climatic swings:

-

Mangrove-fringe shellfish and reef fishes buffered against cool/dry spells; riverine fish and riparian game underwrote lean seasons.

-

Mobility and short-stay landfalls mitigated storm risk on low, water-poor banks.

-

Knowledge of passes, currents, and bank hydrology—the seeds of later navigational traditions—was itself an adaptive asset.

Long-Term Significance

By 7,822 BCE, the West Indies remained lightly and unevenly touched by people: north-coast Hispaniola sustained semi-recurrent Archaic camps, Trinidad & Tobago functioned as a continental bridge, and the Bahama–Caicos–Lesser Antilles served mainly as episodic stopovers.

Yet the physical groundwork was laid—back-reef lagoons, mangrove larders, and bank-edge routes—for the later Ceramic-age colonization of the archipelago. The region’s defining pattern was already in motion: mobility across an aquatic landscape, with estuaries and reefs as granaries and coves as memory-sites that would guide the great peopling to come.