West Indies (1540 – 1683 CE) …

Years: 1540 - 1683

West Indies (1540 – 1683 CE)

Colonization, Contest, and Survival in the Caribbean Sea

Geography & Environmental Context

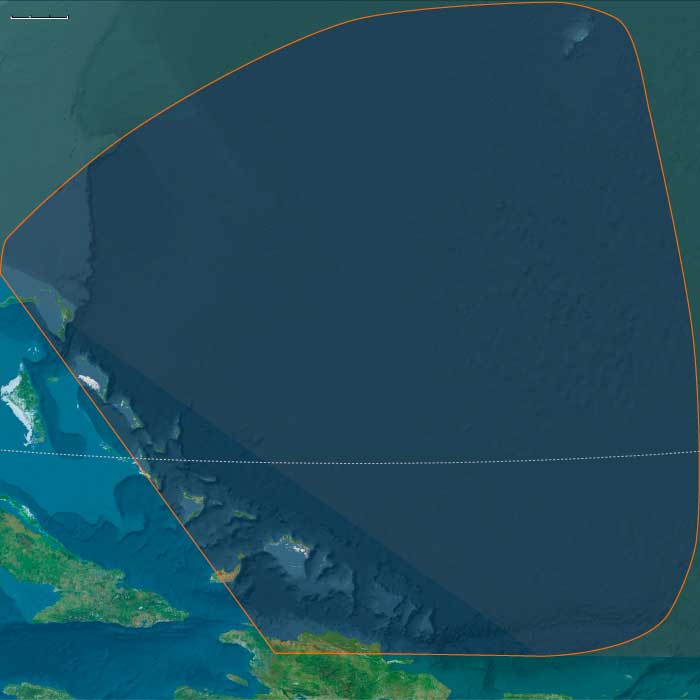

Stretching from the Bahamas and Bermuda to Trinidad, the West Indies formed the hinge between the Atlantic and the Americas—a constellation of limestone banks, volcanic peaks, and coral atolls washed by the Gulf Stream and the northeast trades.

The Little Ice Age sharpened the region’s extremes: cooler winters, recurrent hurricanes, and alternating drought and flood reshaped coasts and crops alike. Reefs and mangroves buffered low islands; fertile volcanic soils sustained sugar, tobacco, and cassava on higher ones. Across this mosaic, imperial rivalries converged upon Indigenous homelands and African diasporas, producing a maritime frontier of empire, enslavement, and endurance.

Northern West Indies – Frontiers of Empire

Bermuda, the Bahamas, and the Turks and Caicos stood at the edge of colonization. Spanish depopulation of the Lucayans left empty shores that English mariners later reoccupied.

Bermuda, settled after the Sea Venture wreck (1609), became an English tobacco colony and shipyard, its cedar forests feeding Atlantic ventures. Northern Hispaniola’s Spanish ranching economy supplied hides and cattle to fleets sailing from Havana.

African labor and creole cultures took root under both Catholic and Anglican regimes. Hurricanes, isolation, and shifting markets demanded self-sufficiency, while piracy and contraband foreshadowed the region’s future role as a maritime crossroads.

Eastern West Indies – Sugar and Resistance

From Hispaniola and Puerto Rico to Barbados, Trinidad, and the Lesser Antilles, the 16th and 17th centuries witnessed population collapse, recolonization, and plantation revolution.

Spanish strongholds reorganized around cattle, timber, and Afro-Caribbean smallholders. Kalinago (Carib) communities held fast to mountainous islands, using canoes and alliances to resist encroachment. Barbados, settled by the English in 1627, rapidly converted to sugar under enslaved African labor, setting a model for the Caribbean’s plantation economy.

Smuggling, maroonage, and syncretic faiths linked islands otherwise divided by empire. Hurricanes and volcanic soils both destroyed and renewed—teaching adaptation through rebuilding and communal ritual.

Western West Indies – Havana and the Spanish Main

In Cuba, Jamaica, and the Bahamas’ inner islands, Spain entrenched its power. Havana, with its castles and arsenals, became the keystone of trans-Atlantic convoys. Cattle ranches and sugar estates expanded inland, worked by enslaved Africans whose traditions reshaped music, food, and devotion—the Virgen de la Caridad del Cobre blending Spanish and African reverence.

Jamaica, sparsely settled under Spain, stood vulnerable to English seizure (1655), while the Caymans and Androsserved as pirate refuges. Hurricanes and drought tested every economy, yet Afro-Caribbean provision gardens and ritual networks sustained survival amid imperial wars.

Cultural and Environmental Resilience

Across the archipelago, the peoples of the West Indies reinvented community under duress.

-

African and Afro-Creole societies forged new languages, religions, and kinship systems blending African, European, and Indigenous traditions.

-

Kalinago and other Indigenous groups persisted through mobility, mountain fortresses, and inter-island canoe routes.

-

Colonial settlers rebuilt ports and plantations after storms, engineering terraces, windmills, and cisterns to survive the climate’s volatility.

Music, festival, and faith carried memory through catastrophe.

Transition (to 1683 CE)

By 1683, the West Indies had become the most contested sea on Earth: Spain’s waning empire guarded Havana and San Juan; England, France, and the Netherlands carved new plantation colonies; piracy, slavery, and contraband linked every harbor.

Indigenous nations endured in refuge, African diasporas transformed labor into culture, and the environment itself—storms, reefs, and fertile volcanic soils—remained the region’s ultimate power.

The Caribbean entered the modern world as both crucible and crossroads: a place where empire met resistance and where survival itself became the deepest art.

People

Groups

- Arawak peoples (Amerind tribe)

- Taíno

- Lucayans

- French people (Latins)

- English people

- Spain, Habsburg Kingdom of

- Spaniards (Latins)

- Eleutheran Adventurers