Northern West Indies (1684–1827 CE): Piracy, Empire, …

Years: 1684 - 1827

Northern West Indies (1684–1827 CE): Piracy, Empire, and Maritime Crossroads

Geographic & Environmental Context

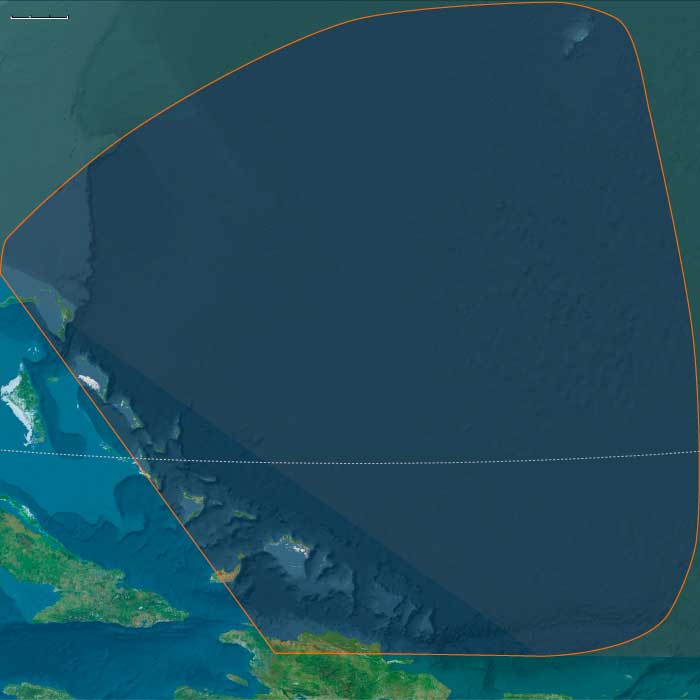

The subregion of Northern West Indies includes Bermuda, the Turks and Caicos, northern Hispaniola, and the Outer Bahamas (Grand Bahama, Abaco, Eleuthera, Cat Island, San Salvador, Long Island, Crooked Island, Mayaguana, Little Inagua, and eastern Great Inagua). The Inner Bahamas belong to the Western West Indies. Anchors included the Bahama Banks, the Caicos Passage, Bermuda’s cedar outcrop, and the Cibao Valley of northern Hispaniola. The region’s shallow cays, reefs, and natural harbors became pivotal in the age of piracy and naval rivalry.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

The Little Ice Age lingered into the 18th century. Hurricanes swept across the Bahamas and Caicos, often devastating fragile settlements. Bermuda endured repeated storms in 1712 and 1719. Hispaniola’s north coast experienced cycles of drought and flood, shaping ranching and farming.

Subsistence & Settlement

-

Northern Hispaniola: Spanish authority waned along the north coast. French buccaneers and settlers encroached from Tortuga and Saint-Domingue. Ranching and contraband trade flourished.

-

Bahamas: English settlement at Nassau (1670) became notorious for piracy. Captains like Blackbeard (Edward Teach) operated from Bahamian waters until Governor Woodes Rogers reestablished order in 1718. Loyalist refugees after the American Revolution resettled the islands.

-

Turks and Caicos: Salt-raking emerged as the economic base, developed by Bermudian and Bahamian settlers using enslaved Africans.

-

Bermuda: Matured as a maritime colony. Cedar-built sloops carried goods across the Atlantic. Tobacco declined, replaced by food crops, salt fish, and shipping. Enslaved Africans formed the majority of the labor force.

Technology & Material Culture

-

Bermudian sloops exemplified fast, maneuverable shipbuilding.

-

Salt pans and stone windmills dotted Turks and Caicos.

-

Ranching in Hispaniola used Spanish herding technologies.

-

African influences shaped basketry, drumming, and foodways across the islands.

Movement & Interaction Corridors

-

Pirate routes crisscrossed the Bahamas, threatening Spanish fleets.

-

British shipping tied Bermuda to North America, the Caribbean, and London.

-

Salt from Turks and Caicos supplied Atlantic markets.

-

Contraband from Hispaniola’s north coast linked ranchers with French Saint-Domingue and Dutch Curaçao.

-

The transatlantic slave trade bound all islands into wider circuits.

Cultural & Symbolic Expressions

-

Catholicism persisted in Hispaniola; African traditions fused with saints’ festivals.

-

Anglican churches anchored Bermuda and Nassau, while enslaved Africans nurtured creole religious practices.

-

Piracy generated its own symbolic culture: flags, legends, and songs of outlaw captains.

-

Salt rakers in Turks and Caicos marked seasons with communal rituals of harvest.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

Settlers rebuilt after hurricanes with sturdier limestone houses and water catchments (notably in Bermuda). Bahamian settlers exploited shallow soils with provision grounds and shifting gardens. African agrarian knowledge preserved crops like okra, cassava, and yams. Hispaniola’s ranchers adapted to drought with mobile herds.

Transition

By 1827 CE, the Northern West Indies was bound tightly into Atlantic empires. Bermuda stood as a fortified British naval station. The Bahamas transitioned from piracy to plantation and Loyalist resettlement. Turks and Caicos anchored salt exports on enslaved labor. Northern Hispaniola lay contested, overshadowed by the rise of French Saint-Domingue and, later, revolutionary Haiti. The subregion was a maritime frontier of slavery, contraband, and empire.

People

Groups

- French people (Latins)

- English people

- Santo Domingo, Captaincy General of

- Santo Domingo, Real Audiencia de

- Spain, Habsburg Kingdom of

- Spaniards (Latins)

- France, (Bourbon) Kingdom of

- Saint Domingue, French Colony of

- Santo Domingo (Spanish Colony)

- France, Kingdom of (constitutional monarchy)

- French First Republic

- Santo Domingo (French Colony)

- Haiti, Republic of

- France, (first) Empire of

- Haiti, Kingdom of northern

- Santo Domingo, Captaincy General of

- France, constitutional monarchy of

- Santo Domingo (Haitian-occupied)

Topics

- Age of Discovery

- Colonization of the Americas, Spanish

- Encomienda system

- Piracy, Golden Age of

- Haitian Revolution