Southern Atlantic (1540–1683 CE): From Phantom Continents …

Years: 1540 - 1683

Southern Atlantic (1540–1683 CE): From Phantom Continents to Passage Islands

Myth, Map, and the Making of the Ocean’s Edge

Geography & Environmental Context

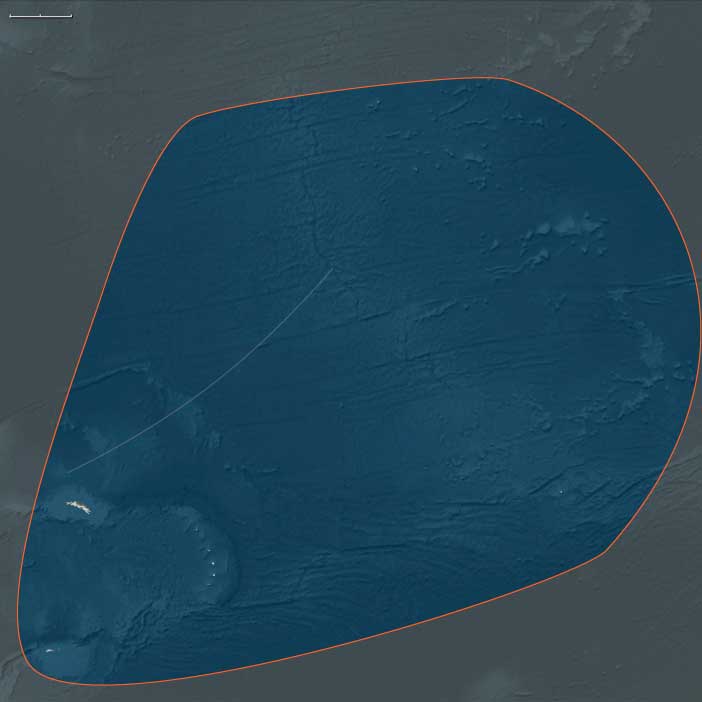

The Southern Atlantic stretches from the cold reaches of the Tristan–Gough–South Georgia arc to the volcanic islets of Saint Helena and Ascension along the Cape Route.

Its subregions—the Southern South Atlantic and the Northern South Atlantic—bookend one of the most remote corridors of the early modern world: a domain of storm belts, fog, and lonely landfalls between Africa and the Americas.

Volcanic summits like Tristan da Cunha rose abruptly from ocean depths; glaciers mantled South Georgia; while Saint Helena’s basalt ramparts and Ascension’s barren cones marked the empire’s first mid-ocean anchors.

Together they formed a maritime frontier where imagination preceded exploration, and navigation turned survival into empire.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

The Little Ice Age deepened climatic extremes.

Cold currents and powerful westerlies sculpted the storm corridors of the south, while trade winds and equatorial calms governed the north.

Ice expanded across South Georgia and the South Orkneys, their coasts locked in fog and snow; farther north, Saint Helena’s uplands caught cloud-fed springs even as Ascension baked under equatorial sun.

For sailors, these contrasts defined the very rhythm of the Atlantic passage—how long they could linger, where they could water, and what they could imagine beyond the horizon.

Subsistence, Settlement, and Survival

For much of this age, the Southern Atlantic remained unpeopled.

The southern islands—Tristan, Bouvet, the South Sandwich and South Orkneys—were visited only by wind and birds, their “discoveries” half fact, half myth.

The northern pair, Saint Helena and Ascension, began as watering rocks—waystations for the Portuguese and later the Dutch and English fleets.

By 1659 the English East India Company had turned Saint Helena into a fortified colony, its terraced gardens and freshwater springs supplying convoys between Asia and Europe.

Ascension remained uninhabited but indispensable, its turtle rookeries feeding passing crews.

Here, human presence clung to the edge of habitability, sustained by goats, citrus groves, and casks of rainwater in a sea otherwise ruled by storm and salt.

Movement & Interaction Corridors

The Southern Atlantic was the ocean’s hinge between hemispheres.

-

The Cape Horn and Cape of Good Hope routes carried fleets from Europe to Asia and the Americas, sweeping past Tristan, Gough, and Saint Helena.

-

The Portuguese Carreira da Índia, and later the VOC and EIC convoys, made the northern islands essential links in global trade.

-

Storm-blown ships and seal-hunting crews reached the southern archipelagos by accident, transforming them into the first “phantom islands” of modern cartography.

Each landfall—real or imagined—became a waypoint on the expanding mental map of the world ocean.

Cultural & Symbolic Expressions

To the 16th- and 17th-century imagination, the Southern Atlantic embodied both myth and mastery.

Its uncharted south merged into the speculative Terra Australis, a continent thought to balance the northern lands.

Maps shaded these seas with conjecture: phantom coasts, “Isles of Fire,” and names of saints and storms.

By contrast, the northern isles became emblems of providence and possession—Saint Helena as a haven of fresh water and faith, its cliffs rising like a fortress ordained for empire.

Sailors’ journals and mariners’ hymns made them sacred ground in a secular sea: proof that even at the world’s edge, order and flag could prevail over chance and chaos.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

Nature governed all.

Penguin rookeries, seal herds, and guano plains in the far south cycled untouched through the centuries; their ecosystems remained pristine under ice and wind.

Farther north, human adaptation blended ingenuity with dependence:

terraced gardens clung to Saint Helena’s slopes; springs were rationed by convoy schedule; shipwrecked sailors harvested turtles and seabirds to survive.

Across this oceanic span, resilience was ecological in the south, strategic in the north—each realm thriving by its own rhythm of endurance.

Transition (to 1683 CE)

By 1683, the Southern Atlantic had passed from myth to map.

The south still whispered of phantom continents, its islands charted in rumor; yet the north stood fortified and colonized, Saint Helena bristling with guns and gardens at the heart of England’s oceanic empire.

Seals and seabirds still ruled the polar seas, but empire had gained a foothold on the trade winds.

In this era, the Southern Atlantic was both wilderness and workshop—a realm where the cold winds of the Little Ice Age met the warm ambitions of global commerce, and where the world’s last empty spaces were first inscribed with human purpose.

Groups

- Portugal, Avizan (Joannine) Kingdom of

- Portuguese Empire

- Portugal, Habsburg (Philippine) Kingdom of

- East India Company, British (The Company of Merchants of London Trading into the East Indies)

- Dutch East India Company (Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie or VOC in Dutch, literally "United East Indies Company")

- Dutch East India Company (Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie or VOC in Dutch, literally "United East Indies Company")

- Portugal, Bragança Kingdom of