South Asia (820 – 963 CE): Pala …

Years: 820 - 963

South Asia (820 – 963 CE): Pala Enlightenment, Pratihara Power, and Chola Renaissance

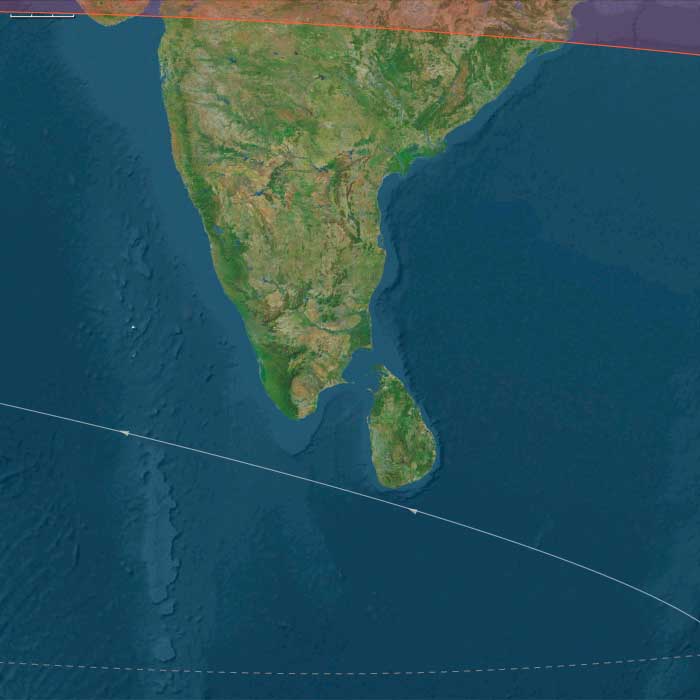

Geographic and Environmental Context

South Asia in this age stretched from the Afghan highlands and Himalayan passes to the southern seas of Sri Lanka and the Maldives, forming a vast subcontinental arc of riverine plains, mountain valleys, and monsoon-fed coasts.

It comprised two complementary worlds:

-

Northern South Asia, anchored in the Indo-Gangetic plains, Kashmir, and the Himalayan foothills, with frontier corridors through Afghanistan and Arakan.

-

Maritime South Asia, embracing the Deccan, Tamilakam, Sri Lanka, and the Indian Ocean islands, oriented toward sea routes and monsoon trade.

Across both, the monsoon system remained the ecological engine—its alternating rains feeding rice, millet, and spice economies that sustained great courts and temple complexes alike.

Climate and Environmental Shifts

The early Medieval Warm Period (c. 800–1200) stabilized monsoons and ensured abundant harvests.

-

Indo-Gangetic plains: reliable rainfall enabled intensive cultivation and urban renewal.

-

Bengal delta: expanded rice agriculture and monastic endowments.

-

Deccan and Tamilakam: seasonal but steady rains; irrigation networks multiplied.

-

Sri Lanka: the great tanks of Anuradhapura reached their hydraulic zenith.

-

Himalayas and frontier zones: salt–grain caravans balanced mountain scarcity and plain abundance.

Overall, this was a time of agrarian prosperity and maritime dynamism.

Societies and Political Developments

Northern South Asia: Pratihara Strength and Pala Enlightenment

-

Gurjara–Pratiharas (North India): From their capital at Kannauj, they dominated the Ganga–Yamuna heartland, checking both Pala expansion from the east and Rashtrakuta incursions from the south. Their reign marked the apex of early Rajput temple-building and Sanskrit culture.

-

Palas (Bengal–Bihar): Under Dharmapala and Devapala, the Pala Empire reached its zenith, extending from Bengal into Assam and Nepal, and patronizing Nalanda and Vikramaśīla, which drew monks from Tibet, China, and Southeast Asia.

-

Afghanistan & Frontier Regions: The Hindu Shahis of Kabul and Gandhara resisted Samanid pressures from the northwest, maintaining the last bastion of pre-Islamic rule in the region.

-

Himalayan Realms:

-

Nepal: The Licchavi dynasty waned as early Malla lineages rose, consolidating the Kathmandu Valley.

-

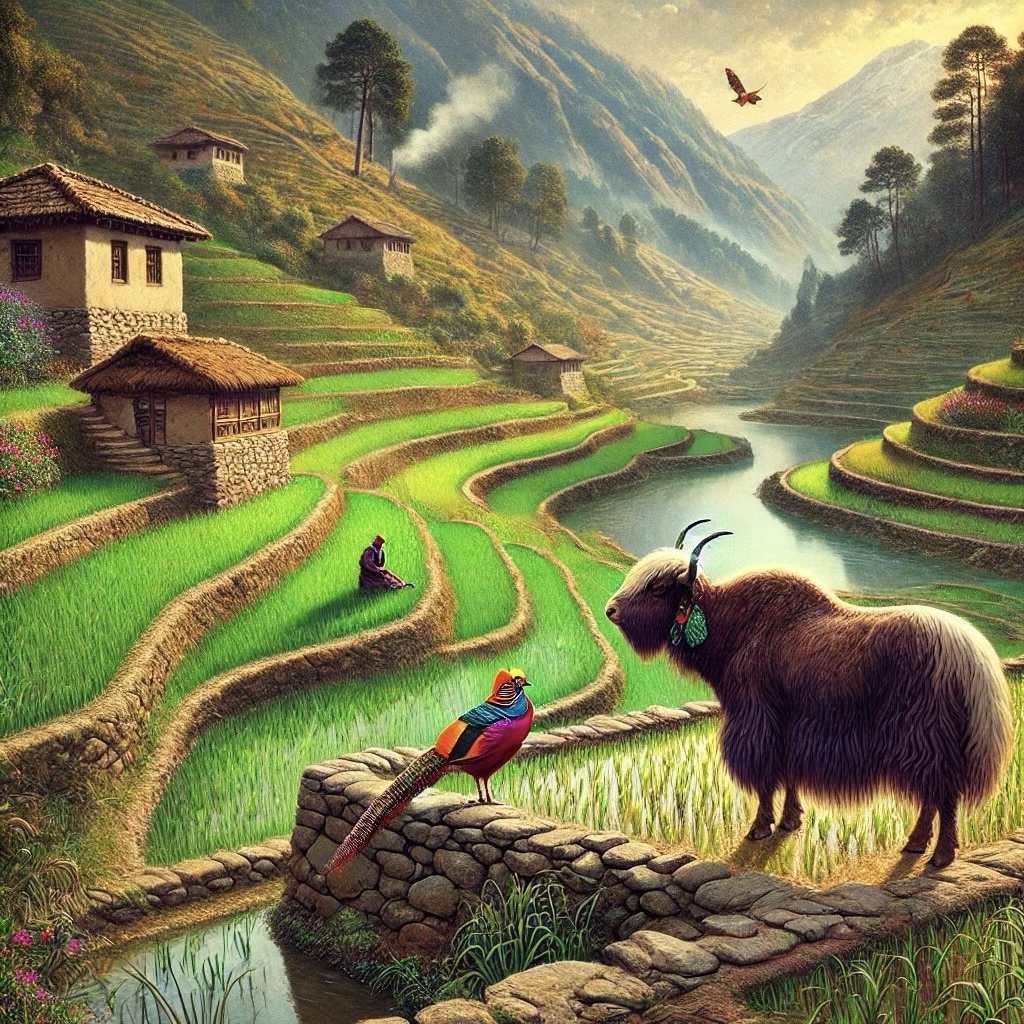

Bhutan: Fragmented highland polities absorbed Tibetan Buddhist influence via cross-Himalayan exchange.

-

-

Arakan and Chindwin Valleys: The Waithali dynasty in Arakan remained Theravāda Buddhist, maintaining trade and religious ties with Bengal and Pagan’s formative centers.

Maritime South Asia: Rashtrakuta Hegemony and Chola Ascent

-

Deccan and Tamilakam:

-

The Rashtrakutas dominated upland Deccan politics from Manyakheta, pressing north and south through cavalry raids.

-

In Tamilakam, the Pallavas of Kanchipuram declined while the Cholas, under early rulers like Vijayalaya (r. 848–871), reestablished control of the Kaveri delta, reviving temple construction and local administration.

-

Cheras in Kerala managed spice forests and timber exports; Pandyas retained influence around Madurai.

-

-

Sri Lanka:

-

The Anuradhapura kingdom reached an apex of irrigation and Buddhist scholarship under Sena I (r. 833–853) and successors.

-

Massive reservoirs and stupas sustained a thriving monastic culture; the island was a hub for Indian Ocean pilgrimage and trade.

-

-

Island Polities:

-

Maldives remained Buddhist, supplying cowries used as currency across Asia.

-

Lakshadweep and Chagos were sparsely inhabited fishing–coconut ecologies.

-

Economy and Trade

-

Agriculture:

-

Wheat and barley dominated Punjab; rice flourished in Bengal, Nepal, and the Tamil plains; millet and pulses anchored Deccan drylands.

-

Advanced irrigation: Doab canals, Bengal embankments, Kaveri–Vaigai tanks, and Anuradhapura reservoirs.

-

-

Artisanal production:

-

Pala bronzes and manuscripts; Kashmiri textiles and Buddhist iconography; Tamil stone temples and bronze icons (precursors of Chola art).

-

-

Trade networks:

-

Overland: Kabul–Punjab horse and silk routes; Himalayan salt–grain trade.

-

Maritime: Bengal textiles and sugar; Kerala’s pepper and cardamom; Sri Lankan pearls and elephants.

-

Ports: Tamralipta, Nagapattinam, Muziris, and Anuradhapura connected with Arab, Persian, and Southeast Asian merchants.

-

Maldives cowries and Sri Lankan gems circulated from Africa to China.

These arteries made South Asia a global trade hinge linking Islamic West Asia, Southeast Asia, and China.

-

Subsistence and Technology

-

Irrigation and Engineering: The Anuradhapura tanks and Kaveri delta weirs exemplified hydraulic mastery; smaller canal systems irrigated the Gangetic plains.

-

Architecture and Art:

-

Pala–Sena brick monasteries, Pratihara–Rajput stone temples, Chola Dravidian shrines, and Sri Lankan stupas.

-

-

Military Systems: Elephants and cavalry dominated plains warfare; fortifications protected upland citadels.

-

Maritime Technology: Multi-masted ships, stitched hulls, and monsoon navigation enabled seasonal crossings between India, Arabia, and Southeast Asia.

Movement and Interaction Corridors

-

Northern corridors: From Kabul–Kandahar into the Punjab and Gangetic plains, extending east to Bengal and Arakan.

-

Southern sea-lanes: From Coromandel and Malabar ports through Sri Lanka to Srivijaya and China’s south coast.

-

Himalayan routes: Carried Buddhist scriptures and artisans between Nalanda, Nepal, Tibet, and Bhutan.

-

Interlinkages: The Chindwin–Irrawaddy corridor connected Bengal to Southeast Asia, while Arab traders reached Gujarat and Ceylon by the monsoon pattern known as the mawsim.

Belief and Symbolism

-

Buddhism: Reached its intellectual zenith under Pala patronage; Nalanda was the beacon of Mahayana–Vajrayana philosophy spreading to Tibet and Southeast Asia.

-

Hinduism: The Pratiharas and Cholas upheld Shaiva and Vaishnava temple networks; local deities integrated into classical forms.

-

Syncretism: In Nepal, Hindu–Buddhist synthesis produced unique pagoda temples; Sri Lanka maintained Theravāda orthodoxy within a pan-Asian pilgrimage sphere.

-

Frontier faiths: Arakan and the Hindu Shahis blended Indic and regional elements; mountain and coastal peoples combined animism with Buddhist and Hindu motifs.

Adaptation and Resilience

-

Hydraulic management mitigated monsoon irregularity.

-

Regional diversity of crops ensured food security.

-

Temple endowments functioned as banks, granaries, and social safety nets.

-

Trade diversification—land, sea, and highland—protected economies from disruption.

-

Cultural pluralism fostered political resilience: Hindu, Buddhist, and local systems coexisted within flexible frameworks of kingship and monastic order.

Long-Term Significance

By 963 CE, South Asia stood as a continental mosaic of empires and maritime hubs:

-

In the north, the Pratiharas held Kannauj, the Palas radiated Buddhist culture, and Rashtrakutas bridged the Deccan.

-

In the south, the Cholas rose amid temple and irrigation revival, the Rashtrakutas ruled the uplands, and Anuradhapura flourished in Ceylon.

-

Across islands and seas, Maldivian and Sri Lankan trade extended India’s reach deep into the Indian Ocean world.

This age set the stage for the Chola maritime empire, the Pala Buddhist renaissance, and the Islamic incursions that would transform the subcontinent’s political and religious horizons in the centuries to come.

Northern South Asia (with civilization) ©2024-25 Electric Prism, Inc. All rights reserved.

Groups

- Tajik people

- Kirat people

- Iranian peoples

- Sindhi people

- Hinduism

- Arab people

- Bengalis

- Pashtun people (Pushtuns, Pakhtuns, or Pathans)

- Jainism

- Buddhism

- Kashmir, Kingdom of

- Buddhism, Tibetan

- Khas peoples

- Indian people

- Buddhism, Mahayana

- Tokharistan (Kushan Bactria)

- Gandhāra

- Bon

- India, Early Medieval

- Rajasthan, Rajput Kingdoms of

- Islam

- Gurjara-Pratihara

- Nepal, Kingdom of

- Palas of Bengal, Empire of the

- Rashtrakuta Dynasty

- Abbasid Caliphate (Baghdad)

- Samanid dynasty

- Tahirid dynasty

- Abbasid Caliphate (Samarra)

- Utpala Dynasty

- Saffarid dynasty

- Shahi Kingdom, or Hindu Shahi

- Abbasid Caliphate (Baghdad)

Topics

Commodoties

- Hides and feathers

- Gem materials

- Domestic animals

- Oils, gums, resins, and waxes

- Textiles

- Fibers

- Strategic metals

- Salt

- Sweeteners

- Lumber

- Money

- Aroma compounds

- Spices

Subjects

- Commerce

- Writing

- Architecture

- Sculpture

- Conflict

- Faith

- Government

- Custom and Law

- Medicine

- Mathematics

- Astronomy

- Philosophy and logic