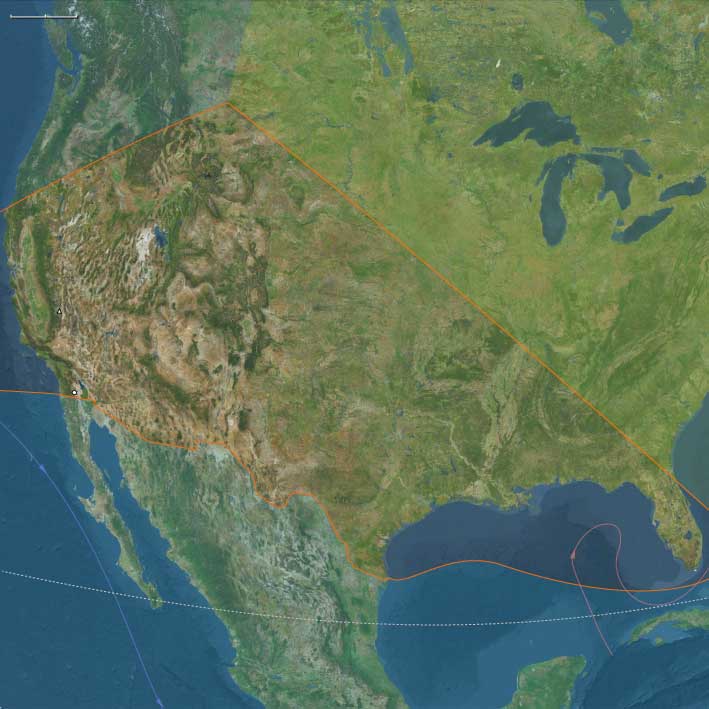

Northern North America (1540 – 1683 CE) …

Years: 1540 - 1683

Northern North America (1540 – 1683 CE)

Enduring Indigenous Worlds and the First Colonial Frontiers

Geography & Environmental Framework

From the Pacific fjords of Alaska and British Columbia to the forests, lakes, and coasts of the Atlantic and Gulf, Northern North America encompassed enormous ecological diversity: glaciated mountains, salmon rivers, oak savannas, prairies, hardwood woodlands, tundra, and the boreal shield.

The Little Ice Age shaped all three subregions. Glaciers advanced along Pacific ranges; Hudson Bay and Greenland froze longer each winter; drought pulses and hurricanes alternated across the Gulf and interior plains. Communities adapted through preservation, trade, and migration, creating resilient social ecologies that endured well before sustained European settlement.

Northwestern North America: Enduring Indigenous Worlds, First Distant Glimpses

Across the Pacific Northwest and sub-Arctic, dense forests, rivers, and coasts sustained prosperous Indigenous nations.

Coastal Tlingit, Haida, Tsimshian, Nuu-chah-nulth, and Coast Salish peoples harvested salmon, halibut, whales, and shellfish from plankhouse villages and celebrated potlatch feasts that redistributed wealth and affirmed law. Interior and plateau groups followed seasonal rounds of hunting, fishing, and root gathering, meeting for great trade fairs at Celilo Falls and other river nodes.

Cedar canoes, totemic art, and carved masks expressed lineage and spirit power. Despite glacial advance and fluctuating salmon runs, storage, trade, and ceremony maintained abundance.

By 1683, the Pacific North had not yet seen sustained European intrusion—Spanish and Russian expeditions lay still ahead—leaving a self-governing world of maritime and riverine civilizations poised at the threshold of contact.

Northeastern North America: Fishermen, Colonists, and Resilient Woodland Worlds

From Florida’s estuaries to Greenland’s fjords, woodland, prairie, and coastal peoples adapted to cooling climates and expanding Atlantic fisheries.

Iroquoian and Algonquian farmers maintained maize-bean-squash agriculture alongside hunting and fishing; in the far north, Inuit extended seal hunting over newly thickened sea-ice. Rivers and lakes served as highways binding interior nations to the first European colonies.

By the early 1600s, French Acadia and Quebec, Dutch New Netherland, English New England and Chesapeake, and Spanish Florida had taken root. Furs, fish, and forests tied Indigenous and European economies together, while epidemics and warfare began to reshape demographics.

The Iroquois Confederacy rose as a major political power; missionaries, traders, and settlers built fragile alliances and rivalries.

By 1683, a multicultural mosaic extended from cod banks to Great Lakes forests—an Atlantic frontier still overwhelmingly Indigenous in its interior but irrevocably drawn into global circuits.

Gulf and Western North America: Spanish Entradas and Enduring Societies

South and west of the Mississippi, diverse Indigenous polities dominated vast landscapes.

Pueblo farmers of the Rio Grande maintained irrigated fields and kivas; Navajo and Apache expanded herding and raiding economies; California’s coastal and island tribes prospered on acorns, fisheries, and trade networks.

Spanish expeditions under de Soto and Coronado probed but never mastered the interior. Missions and forts appeared in Florida and New Mexico, yet survival depended on Indigenous alliances. The horse—introduced by Spaniards—was transforming mobility across the plains.

By 1683, the Gulf and West remained largely autonomous: European outposts clung to coasts and valleys, while Native confederacies, pueblos, and nomadic nations adapted horses, firearms, and trade to their advantage.

Cultural and Ecological Themes

Across the northern continent, art and ceremony anchored identity:

-

Totemic carving and potlatch law on the Pacific;

-

Wampum diplomacy and council fires in the Great Lakes and St. Lawrence;

-

Kachina dances and Green Corn rites in the Southwest and Southeast.

Environmental adaptation was everywhere sophisticated—salmon and seal preservation in the Northwest, maize granaries in the East, irrigation and acorn storage in the arid West. Climatic stress during the Little Ice Age spurred innovation rather than collapse.

Transition (to 1683 CE)

By 1683, Northern North America was a continent of enduring Indigenous sovereignties threaded with the first strands of European empire. Spanish forts, French missions, English farms, and Dutch ports dotted its edges, while vast interiors remained guided by Native diplomacy, ecology, and exchange. The Little Ice Age’s rigors had tested but not broken subsistence systems.

The next age would see intensified colonization, new alliances, and epidemic shocks—but also the continuity of Native landscapes, languages, and cosmologies that had already sustained the North for millennia.

People

Groups

- Mound Builders

- Dutch people

- Mississippian culture

- Caddoan Mississippian culture

- Iroquois (Haudenosaunee, also known as the League of Peace and Power, Five Nations, or Six Nations)

- Algonquin, or Algonkin, people (Amerind tribe)

- Basque people

- Maliseet, or Wolastoqiyik, people (Amerind tribe)

- Mi'kmaq people (Amerind tribe)

- Thule people

- Penobscot people (Amerind tribe)

- Ho-Chunk (Amerind tribe)

- English people

- France, (Valois) Kingdom of

- Mohawk people (Amerind tribe)

- Osage Nation (Amerind tribe)

- Wyandot, or Wendat, or Huron people (Amerind tribe)

- England, (Tudor) Kingdom of

- Tuscarora (Amerind tribe)

- Catawba people (Amerind tribe)

- Quapaw, or Arkansas (Amerind tribe)

- Omaha (Amerind tribe)

- Pawnee (Amerind tribe)

- Kaw, or Kanza, people (Amerind tribe)

- Caddo (Amerind tribe)

- Hidatsa people (Amerind tribe)

- Shoshone, Shoshoni, or Snakes (Amerind tribe)

- Crow people, aka Absaroka or Apsáalooke (Amerind tribe)

- Cheyenne people (Amerind tribe)

- Iowa (Amerind tribe)

- Ponca (Amerind tribe)

- Yuchi (Amerind tribe)

- Kiowa people (Amerind tribe)

- Plains Apache, or Kiowa Apache; also Kiowa-Apache, Naʼisha, Naisha (Amerind tribe)

- Massachusett people (Amerind tribe)

- Dakota, aka Santee Sioux (Amerind tribe)

- Yankton Sioux Tribe

- Cherokee, or Tsalagi (Amerind tribe)

- Seneca (Amerind tribe)

- Cayuga people(Amerind tribe)

- Onondaga people (Amerind tribe)

- Oneida people (Amerind tribe)

- Lakota, aka Teton Sioux (Amerind tribe)

- Innu (Montagnais, Naskapi) (Amerind tribe)

- Iroquoians, St. Lawrence

- Susquehannock (Amerind tribe)

- Narragansett people (Amerind tribe)

- Pequots (Amerind tribe)

- Wampanoag (Amerind tribe)

- Protestantism

- New France (French Colony)

- France, (Bourbon) Kingdom of

- Acadian people

- French Canadians

- Ulster Scots people (Scots-Irish)

- Virginia (English Colony)

- Newfoundland (English Colony)

- New Netherland (Dutch Colony)

- Maine, Province of

- Virginia (English Crown Colony)

- Massachusetts Bay Colony (sometimes called the Massachusetts Bay Company, for its founding institution)

- Plymouth Colony (English Colony)

- (Connecticut) River Colony (English)

- New England Confederation (United Colonies of New England)

- Connecticut (English Crown Colony)

- New Netherland (Dutch Colony, restored)

- New Hampshire (English Crown Colony)

Topics

- Little Ice Age (LIA)

- Colonization of the Americas, French

- Little Ice Age, Warm Phase II

- Colonization of the Americas, English

- Beaver Wars, or French and Iroquois Wars

- Colonization of the Americas, Dutch

- Pequot War

- King Philip's War

Commodoties

- Fish and game

- Gem materials

- Colorants

- Domestic animals

- Grains and produce

- Ceramics

- Strategic metals

- Tobacco

Subjects

- Commerce

- Environment

- Decorative arts

- Conflict

- Exploration

- Faith

- Government

- Custom and Law

- Technology

- Human Migration