Northeast Asia (1108 – 1251 CE): Jurchen …

Years: 1108 - 1251

Northeast Asia (1108 – 1251 CE): Jurchen Ascendancy, Mongolic Expansion, and the Transformation of the Steppe

Geographic and Environmental Context

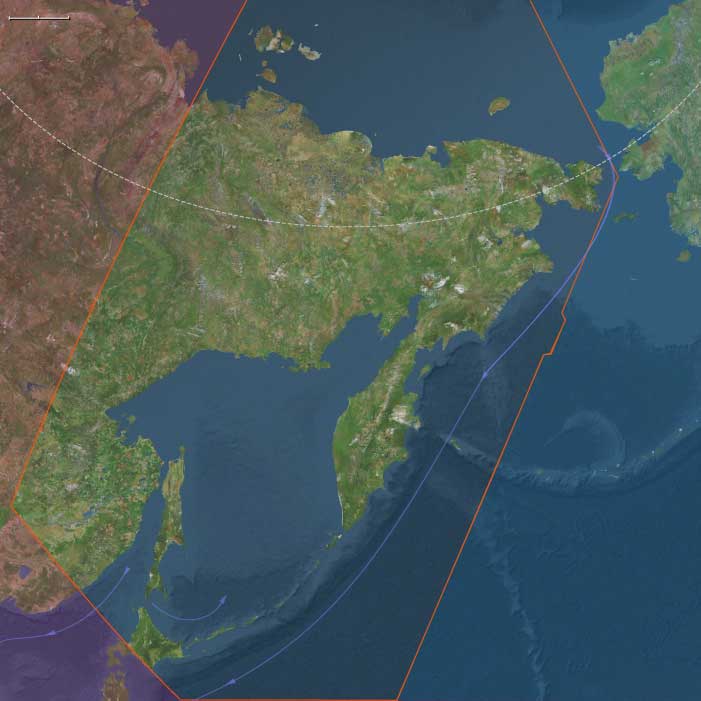

Northeast Asia includes the easternmost areas of Siberia (east of 130°E), the extreme northeastern Heilongjiang region of China, the Chukchi Peninsula, the Kamchatka Peninsula, the Russian Far East, the Amur River basin, and Hokkaido.

-

This was a land of vast forests, tundra, and river valleys, bounded by the Pacific coastlines of the Sea of Okhotsk and the Bering Sea.

-

The Amur River basin provided fertile lowlands for agriculture and fishing.

-

The Kamchatka and Chukchi peninsulas remained sparsely inhabited, sustaining hunting, fishing, and reindeer herding.

-

Hokkaido was home to Ainu communities, distinct in culture from the Japanese heartlands to the south.

Climate and Environmental Shifts

-

The Medieval Warm Period moderated winters slightly, improving agricultural conditions in the Amur basin and supporting population growth among farming societies.

-

Despite this, harsh winters continued in Siberia and the Kamchatka–Chukchi north, where subsistence remained primarily hunting and fishing.

-

Stable marine ecosystems supported rich fisheries along the Pacific coast.

Societies and Political Developments

-

Jurchen Empire: In 1115, the Jurchens (ancestors of the Manchus) established the Jin dynasty in northern China after overthrowing the Khitan Liao. Their homeland lay in the forests and river valleys of Northeast Asia, where they combined hunting, fishing, and agriculture.

-

Mongolic Expansion: Mongolic-speaking groups began pressing eastward, disrupting steppe and forest peoples, foreshadowing the Mongol conquests of the 13th century.

-

Tungusic peoples remained widespread across the Amur and Ussuri basins, maintaining semi-sedentary lifeways and tribute relations with more powerful neighbors.

-

Ainu of Hokkaido maintained autonomous chiefdoms, engaged in trade with northern Honshu, and relied on hunting, fishing, and horticulture.

-

Chukchi and Koryak in the far northeast preserved mobile, kinship-based societies oriented to reindeer herding, fishing, and sea mammal hunting.

Economy and Trade

-

Amur Basin agriculture centered on millet, soybeans, and hemp, supplemented by fishing and hunting.

-

The Jurchen economy integrated tribute, farming, and control over northern Chinese trade networks.

-

Ainu traded furs, marine products, and hawk feathers with Japan, receiving iron tools, rice, and cloth.

-

Maritime and riverine exchange circulated furs, ginseng, honey, salt, and metals across the Amur, Ussuri, and Pacific coast.

-

The steppe corridor enabled the movement of horses and livestock, linking the region to broader Inner Asian exchange.

Subsistence and Technology

-

Jurchen farming combined slash-and-burn techniques with permanent fields in the Amur basin.

-

Composite bows, iron weapons, and armored cavalry made the Jurchens formidable military opponents.

-

Ainu technologies included pit dwellings, lacquered woodcraft, and fishing tools adapted to Hokkaido’s environment.

-

Chukchi and Koryak used skin boats (umiaks), dog sleds, and reindeer herding to survive in tundra ecologies.

-

Pottery, textiles, and wooden ritual implements reflected both practicality and cultural identity.

Movement and Interaction Corridors

-

The Amur River functioned as a major artery of movement, uniting farming and fishing settlements.

-

The Sea of Okhotsk connected maritime communities by canoe and larger boats.

-

Overland steppe routes tied Jurchens and Mongolic groups to northern China and Central Asia.

-

Hokkaido maintained steady interaction with Honshu through trade and occasional conflict.

-

The Bering Strait linked Chukchi to Alaskan Inuit, sustaining trans-Arctic cultural continuities.

Belief and Symbolism

-

Jurchen religion combined shamanistic traditions with Buddhist and Daoist elements adopted from China.

-

Ainu spirituality venerated animal spirits, especially the bear (kamuy), with rituals emphasizing reciprocity between humans and nature.

-

Chukchi and Koryak cosmologies centered on animist traditions, with shamans mediating with spirits of sea and tundra.

-

Rituals tied to hunting, fishing, and herding reinforced ecological balance and communal identity.

Adaptation and Resilience

-

Agricultural intensification and tribute networks sustained the Jurchens, enabling the rise of the Jin dynasty.

-

Mobile pastoralism and maritime hunting supported Chukchi, Koryak, and Ainu resilience in harsh climates.

-

Trade in furs, iron, and marine resources linked scattered societies into a resilient web of exchange.

-

Flexibility in combining farming, hunting, and fishing allowed communities to adapt to environmental variability.

Long-Term Significance

By 1251 CE, Northeast Asia had been reshaped by the Jurchen rise to power, the expansion of Mongolic peoples, and the enduring resilience of Ainu, Chukchi, and Koryak lifeways. The region’s integration into larger East Asian and Inner Asian systems foreshadowed the transformative impact of the Mongol Empire, while maintaining its deep-rooted traditions of shamanism, maritime exchange, and ecological adaptation.

Groups

- Koryaks

- Nivkh people

- Ainu people

- Buddhism

- Taoism

- Mohe people

- Okhotsk culture

- Satsumon culture

- Jurchens

- Liao Dynasty, or Khitan Empire

- Jin Dynasty (Chin Empire), Jurchen

- Jin Dynasty (Chin Empire), Jurchen

- Jin Dynasty (Chin Empire), Jurchen

Topics

Commodoties

- Fish and game

- Hides and feathers

- Gem materials

- Glass

- Domestic animals

- Grains and produce

- Strategic metals

- Salt

- Sweeteners

- Spices