Northeast Eurasia (964 – 1107 CE): Liao …

Years: 964 - 1107

Northeast Eurasia (964 – 1107 CE): Liao Frontiers, Jurchen Leagues, and the Fur–Silver Networks of the Forests

Geographic and Environmental Context

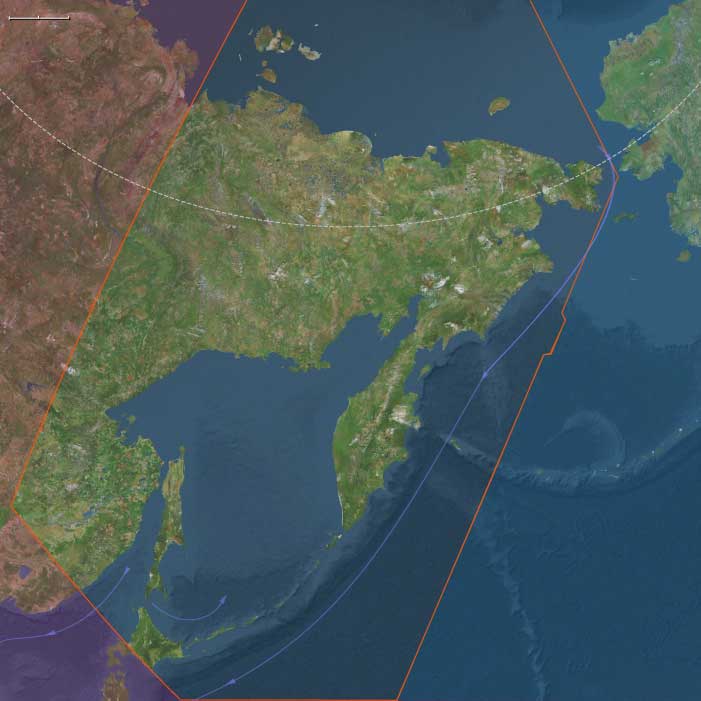

Northeast Eurasia stretched from the Carpathian frontier of Kievan Rus’ and the Volga steppes through the West Siberian Plain, Amur–Heilongjiang basin, and Russian Far East to Hokkaidō and the Okhotsk coast.

This immense region linked the Eurasian forest and steppe worlds—taiga, tundra, and riverine plains—into a web of exchange reaching both the Byzantine–Islamic and East Asian empires.

Major river systems—Volga, Ob, Irtysh, Yenisei, Amur, and Dnieper—functioned as arteries of movement, while the Okhotsk Sea, Sakhalin–Hokkaidō corridor, and northern Pacific coasts sustained maritime hunting and limited trade.

Climate and Environmental Shifts

The Medieval Warm Period (c. 950–1250) slightly softened the subarctic climate.

-

Southern Siberia and the Amur basin saw longer growing seasons that permitted limited millet cultivation.

-

Forest-steppe margins expanded northward, improving grazing for Kyrgyz and Kipchak herds.

-

Salmon runs increased in the Amur and Okhotsk regions, while reduced ice along the Sea of Okhotsk opened new sea lanes.

These stable ecologies encouraged denser settlement in river valleys and intensified long-distance trade in furs, fish, and forest goods.

Societies and Political Developments

Kievan Rus’ and the Fall of Khazaria

In the southwest, Prince Sviatoslav of Kiev (r. 945–972) destroyed the Khazar Khaganate (964–969), ending centuries of steppe control over the Volga–Caspian gateway.

The victory transferred riverine hegemony to the Kievan Rus’, who dominated the Dnieper trade route to Byzantium and extended tributary claims northward to Novgorod and eastward toward the Volga Bulgars.

Vladimir I (r. 980–1015) Christianized Rus’ in 988, aligning it with Byzantine Orthodoxy; his son Yaroslav the Wise (r. 1019–1054) codified law and patronized cathedrals.

By the 11th century, Rus’ had become a federation of princely centers—Kiev, Novgorod, Smolensk, Chernigov—linked by rivers and fortified towns.

To the east, Volga Bulgars, Islamized in 922, prospered as intermediaries in the fur and silver trade, replacing Khazaria as the Islamic world’s northern supplier.

The Steppe and Taiga Frontiers

Beyond the settled Slavic–Finnic belt stretched the forest–steppe mosaics of Siberia.

The Yenisei Kyrgyz, heirs to the Uyghurs, maintained a khaganate in the Minusinsk Basin, collecting tribute from taiga hunters.

To their west, Kipchak confederations rose after the decline of the Kimeks, expanding along the Ishim–Irtysh corridor and absorbing Turkic groups.

By 1107 they dominated the western Siberian steppe, pressing Oghuz tribes westward toward Khwarazm and the Caspian, while coexisting with forest Ob-Ugric and Samoyedic hunters farther north.

The Forest and Riverine Peoples

Across the taiga, Ob-Ugric (Khanty, Mansi), Selkup, Ket, Nenets, and Evenki clans maintained kin-based communities centered on fishing, trapping, and reindeer herding.

Shamanic leadership coordinated seasonal migration and exchange.

To the east, Amuric-speaking Nivkh, Ulch, and Nanai (Hezhe) prospered on salmon harvests and seal hunts, sending tribute furs and falcons south to the Khitan Liao Empire (907–1125).

The Liao integrated the Amur tributaries into a regulated frontier system without annexation, trading iron and silk for pelts and ginseng.

The Rise of the Jurchen and Liao Frontiers

Among the Mohe descendants in the upper Amur, Jurchen tribal leagues formed by the 11th century, uniting millet farmers, hunters, and horsemen under chieftains who acknowledged, yet defied, Liao authority.

These confederations would later generate the Jin dynasty (1115–1234).

Further south, Song China traded indirectly through Liao markets, absorbing furs and ginseng from these northern intermediaries.

The Pacific Fringe and Hokkaidō

Along the Okhotsk coast, Koryak, Itelmen, and Chukchi sustained sea-mammal hunting and reindeer nomadism, bartering ivory and hides westward.

On Hokkaidō, the waning Okhotsk culture merged with the Satsumon tradition, producing a distinct Ainuethnogenesis—combining fishing, deer hunting, and millet farming.

By the late 11th century, the Ainu occupied northern Hokkaidō, trading dried salmon and hides to Honshū in exchange for iron tools and rice from Japanese merchants across the Tsugaru Strait.

Economy and Trade

Northeast Eurasia’s economy was anchored in furs, fish, forest goods, and silver.

-

Exports: sable, ermine, fox, beaver, walrus ivory, eagle feathers, and slaves.

-

Imports: iron, textiles, beads, salt, and grain from Liao, Khwarazm, and Rus’.

-

Dirham silver from the Samanids dominated early trade via Volga Bulgars and Khwarazm, but its decline after c. 970 forced northern merchants into hack-silver and barter economies.

-

By the 11th century, Byzantine coins, Rus’ bullion, and Liao silk replaced Islamic silver as the region’s exchange media.

Key entrepôts included Kiev, Khwarazm, Novgorod, Yeniseisk, and Amur tributary posts.

In the far northeast, Hokkaidō and Sakhalin exchanged furs and dried fish with Japan, while Okhotsk–Kamchatka trade linked sea hunters to inland reindeer peoples.

Subsistence and Technology

Riverine and forest technologies sustained high productivity:

-

Fisheries: wicker traps, bone-tipped harpoons, and drying racks for salmon and sturgeon.

-

Reindeer and sled economies among Evenki and Nenets facilitated winter transport.

-

Boats and sledges moved furs along the Ob, Irtysh, and Amur; dog teams linked Arctic settlements.

-

Agriculture: limited millet in southern Amur and northern Hokkaidō; plow farming in Rus’ and Volga Bulgar fields expanded rapidly.

-

Metals: iron from Liao and Rus’ artisans diffused east; copper kettles, bronze ornaments, and silver dirhams functioned as prestige goods.

-

Architecture: from timber fortresses and cathedrals in Kiev to semi-subterranean huts and reindeer tents in Siberia and the Amur valley.

Movement and Interaction Corridors

-

Dnieper–Black Sea route (“Road to the Greeks”) carried Rus’ and Byzantine commerce.

-

Volga–Kama–Caspian route sustained Islamic markets via Volga Bulgars.

-

Ob–Irtysh–Khwarazm corridor linked Siberian furs to Transoxiana.

-

Yenisei–Sayan passes transmitted Kyrgyz tribute to Inner Asia.

-

Amur River connected taiga villages to Liao markets.

-

Coastal Okhotsk routes united Sakhalin, Kamchatka, and Hokkaidō.

-

Tsugaru Strait and Sea of Japan channels tied the Ainu north and Japanese south into reciprocal exchange.

Belief and Symbolism

Religion and ritual across Northeast Eurasia reflected the interaction of shamanic cosmology, Tengri sky cults, Orthodox Christianity, Islam, and Buddhism.

-

Forest and Arctic peoples venerated sky, river, and animal spirits; shamans mediated through trance and drum.

-

Kyrgyz and Kipchaks upheld Tengri rites and horse burials while absorbing Islamic influences via Khwarazm.

-

Rus’ adopted Orthodox Christianity (988), replacing pagan temples with cathedrals and monasteries.

-

Volga Bulgars institutionalized Islamic law, blending steppe and mercantile traditions.

-

Amur peoples honored river and salmon spirits, while Ainu bear rituals (iyomante) expressed reciprocity with animal deities.

-

Koryak and Chukchi mythologies revolved around whale and reindeer gods, binding subsistence to cosmology.

Adaptation and Resilience

Ecological and political flexibility ensured survival in the region’s extremes:

-

Diversified subsistence (fish, fur, millet, and reindeer) buffered environmental risk.

-

Seasonal mobility along rivers and ice routes enabled resource sharing and trade.

-

Hybrid economies combined local foraging with tribute or barter ties to Rus’, Liao, and Islamic markets.

-

Cultural fusion—Ainu blending of Okhotsk and Satsumon; Jurchen synthesis of forest and agrarian lifeways—created enduring adaptive identities.

-

Religious pluralism allowed coexistence between new and traditional cosmologies.

Long-Term Significance

By 1107 CE, Northeast Eurasia had become a connected frontier zone—ecologically marginal yet economically indispensable to both continental empires and maritime exchange:

-

Kievan Rus’ matured as a Christian commonwealth balancing Byzantine and steppe influences.

-

Volga Bulgars dominated Islamic northern trade.

-

Kipchaks and Kyrgyz shaped the steppe balance, linking taiga furs to southern silver.

-

Amuric and Tungusic societies joined Liao tributary networks while remaining autonomous.

-

Jurchen tribal leagues emerged, poised to build the Jin Empire.

-

Ainu identity crystallized in Hokkaidō, maintaining cultural resilience against later Japanese encroachment.

Across this vast arc—from the Dnieper to the Okhotsk—rivers, forests, and steppes formed a single northern system of exchange that sustained Eurasian commerce, belief, and adaptation for centuries to come.

Groups

- Chukchi

- Koryaks

- Ulch people

- Nivkh people

- Evens, or Eveny

- Ainu people

- Khitan people

- Mohe people

- Satsumon culture

- Japan, Heian Period

- Itelmens

- Nanai people

- Jurchens

- Liao Dynasty, or Khitan Empire

- Evenks

Commodoties

- Fish and game

- Weapons

- Hides and feathers

- Gem materials

- Glass

- Domestic animals

- Grains and produce

- Strategic metals

- Slaves

- Manufactured goods

- Spices