Northeast Asia (964 – 1107 CE): Liao …

Years: 964 - 1107

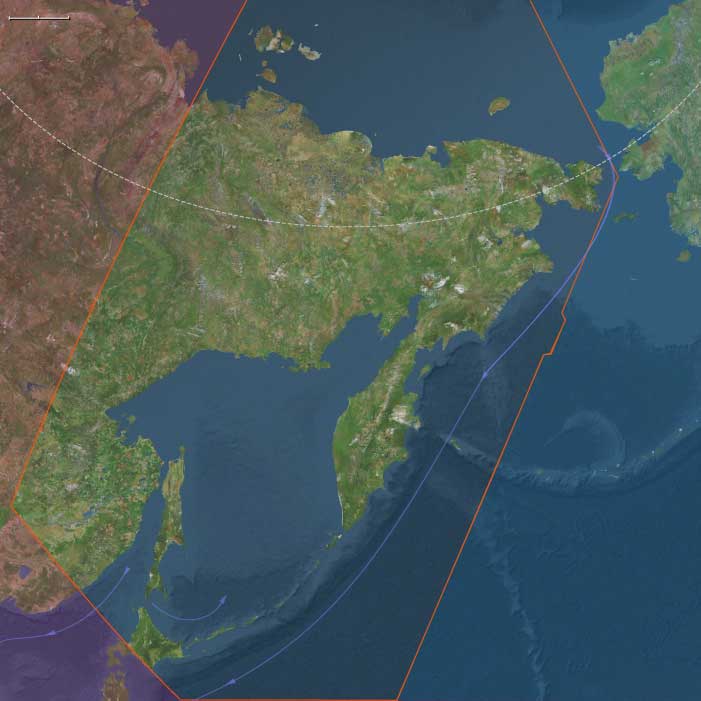

Northeast Asia (964 – 1107 CE): Liao Expansion, Ainu Consolidation, and Amuric–Tungusic Networks

Geographic and Environmental Context

Northeast Asia includes Siberia east of the Lena River basin to the Pacific Ocean, the Russian Far East (excluding southern Primorsky Krai/Vladivostok), the island of Hokkaidō above its southwestern peninsula, and China’s extreme northeastern Heilongjiang Province.

-

A cold-temperate and subarctic realm: taiga forests of larch and pine, salmon-rich rivers (Amur, Ussuri), sea-ice coasts along the Okhotsk, and volcanic uplands in Kamchatka.

-

Populations were dispersed, organized around riverine fisheries, coastal sea-mammal hunting, reindeer herding, and forest foraging, with exchange linking them southward into the orbit of larger continental states.

Climate and Environmental Shifts

-

The Medieval Warm Period (c. 950–1250 CE) brought slightly milder conditions, lengthening growing seasons along the Amur and southern Hokkaidō, allowing limited millet cultivation.

-

More abundant salmon runs and stable forest ecologies supported higher populations in the river valleys.

-

Reduced sea ice in some coastal years eased Okhotsk Sea navigation, intensifying maritime exchange.

Societies and Political Developments

Amur–Heilongjiang Basin

-

Nivkh, Ulch, Nanai (Hezhe), and related Amuric-speaking peoples thrived along the lower Amur and Ussuri.

-

Organized in clan-based villages, they coordinated salmon harvests and seal hunts while sending tribute furs, ginseng, and falcons southward to the Khitan Liao Empire (907–1125).

-

The Liao incorporated Amur tributaries into their frontier system, formalizing exchange while avoiding direct conquest.

-

Mohe groups, ancestral to the Jurchen, practiced slash-and-burn millet farming, pig raising, and hunting. By the 11th century they consolidated into Jurchen tribal leagues that would later birth the Jin dynasty (1115–1234).

Siberian Taiga and Tundra Peoples

-

Evenki and Even (Tungusic reindeer herders) expanded their ranges across interior taiga, balancing fur trapping with semi-domesticated reindeer economies.

-

Koryak and Itelmen in Kamchatka specialized in salmon fishing and sea-mammal hunts.

-

Chukchi herders on the northeast peninsula strengthened reindeer nomadism, with clan councils and ritual leaders holding authority.

-

These groups remained autonomous, but participated in fur–ivory trade with Amur peoples and indirectly with Liao brokers.

Hokkaidō

-

The Okhotsk culture waned during this age, gradually absorbed by the Satsumon culture (Ainu ancestors).

-

Ainu ethnogenesis accelerated: blending Okhotsk maritime lifeways with Satsumon agriculture (millet, barley), deer hunting, and salmon fishing.

-

By the late 11th century, distinct Ainu identity crystallized in northern Hokkaidō, while the southwest remained contested with Wajin (Japanese) settlers from Honshū.

Economy and Trade

-

Furs (sable, fox, ermine), seal and whale products, walrus ivory, and falcons flowed down the Amur to Liao markets, entering China and Central Asia.

-

Ginseng and medicinal herbs from Heilongjiang became prized commodities.

-

Ainu exported dried salmon, eagle feathers, and deer hides across the Tsugaru Strait to Honshū, receiving iron tools, lacquerware, and rice in exchange.

-

Chukchi and Koryak traded walrus ivory and seal skins westward through taiga intermediaries.

Subsistence and Technology

-

Riverine technologies: wicker traps, weirs, and drying racks for salmon.

-

Maritime hunting gear: toggling harpoons, skin-covered boats, and bone-tipped lances.

-

Taiga mobility: skis, snowshoes, dog sleds, and reindeer transport.

-

Agriculture: limited millet and barley in southern Amur and northern Hokkaidō, supplementing foraging.

-

Iron tools and weapons entered steadily via Liao and Japanese traders, but bone, stone, and antler remained essential.

Movement and Interaction Corridors

-

Amur River system: main artery linking forest hunters, fishing villages, and Liao tributary centers.

-

Coastal Okhotsk routes: connected Sakhalin, Kamchatka, and Hokkaidō, sustaining Okhotsk–Ainu cultural blending.

-

Tsugaru Strait: bridge between Hokkaidō Ainu and Japanese traders in northern Honshū.

-

Over-ice travel in winter enabled seasonal fairs along frozen rivers and bays.

Belief and Symbolism

-

Amur peoples venerated river and salmon spirits, with shamans conducting rituals at seasonal fishing sites.

-

Tungusic groups maintained sky and fire cults; shamans mediated clan life and hunting luck.

-

Ainu developed distinctive bear rituals (iyomante), expressing reciprocity with powerful animal spirits.

-

Koryak and Chukchi mythologies centered on whale and reindeer deities, binding subsistence to cosmology.

-

Burial rites often included hunting gear, animal bones, and antler regalia, signifying continued bonds with prey animals.

Adaptation and Resilience

-

Diversified economies (fish, game, limited cultivation) buffered climate swings.

-

Seasonal mobility ensured access to salmon, reindeer, and seals, reducing overdependence on one resource.

-

Trade alliances with Liao and Japanese polities allowed steady access to iron, grain, and prestige goods, while maintaining autonomy.

-

Ainu consolidation in Hokkaidō created cultural resilience, blending Okhotsk maritime and Satsumon agrarian elements.

Long-Term Significance

By 1107 CE, Northeast Asia had become a critical fur and frontier zone, woven into wider Eurasian systems through the Liao Empire and Japanese trade:

-

Amur peoples integrated into tributary networks while preserving autonomy.

-

Jurchen tribal leagues began to coalesce, foreshadowing their rise as a great power in the next century.

-

Ainu identity crystallized in Hokkaidō, sustaining distinct cultural lifeways into later centuries.

-

Siberian taiga and tundra groups endured with their resilient multi-resource economies, forming the ecological foundation for later contacts with Mongols, Chinese, and eventually Russians.

Northeast Asia in this age remained a frontier of forest, sea, and ice, simultaneously peripheral and indispensable to the great empires of Inner Asia and East Asia.

Groups

- Chukchi

- Koryaks

- Ulch people

- Nivkh people

- Evens, or Eveny

- Ainu people

- Khitan people

- Mohe people

- Satsumon culture

- Japan, Heian Period

- Itelmens

- Nanai people

- Jurchens

- Liao Dynasty, or Khitan Empire

- Evenks

Commodoties

- Fish and game

- Weapons

- Hides and feathers

- Gem materials

- Glass

- Domestic animals

- Grains and produce

- Strategic metals

- Slaves

- Manufactured goods

- Spices