Northeast Asia (28,577 – 7,822 BCE): Upper …

Years: 28577BCE - 7822BCE

Northeast Asia (28,577 – 7,822 BCE): Upper Paleolithic II — Beringian Standstill, Early Pottery Horizons, and Salmon Towns

Geographic and Environmental Context

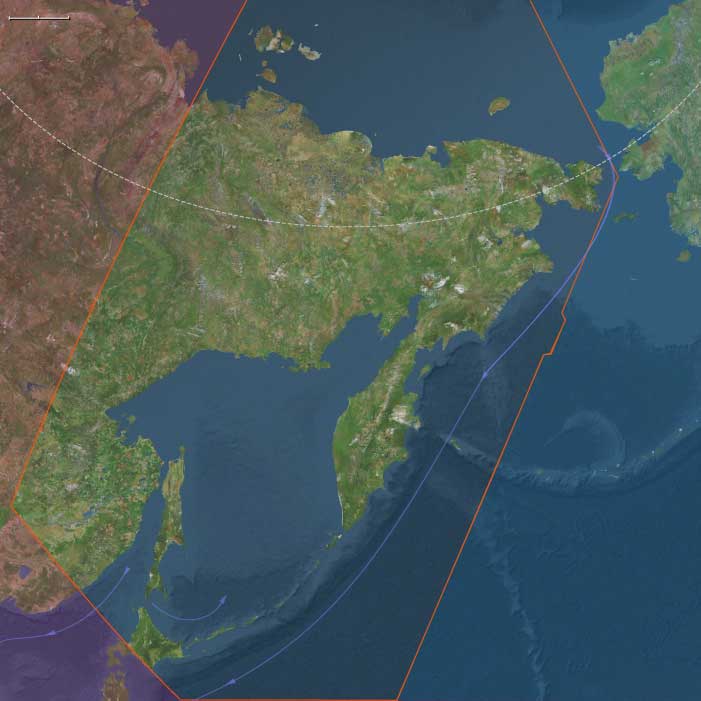

Northeast Asia includes eastern Siberia east of the Lena River to the Pacific, the Russian Far East (excluding the southern Primorsky/Vladivostok corner), northern Hokkaidō (above its southwestern peninsula), and extreme northeastern Heilongjiang.

-

Anchors: the Lower/Middle Amur and Ussuri basins, the Sea of Okhotsk littoral (Sakhalin, Kurils), Kamchatka, the Chukchi Peninsula (with Wrangel Island offshore), northern Hokkaidō, and seasonally emergent shelves along the Bering Sea and northwest Pacific.

Climatic Crisis and Population Transformation During the LGM

Between roughly 28,500 and 20,000 years ago, the onset of the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM) profoundly altered Northeast Asia. Ice sheets, permafrost expansion, and ecological fragmentation reduced habitable zones across Siberia.

During and immediately after this period, the Ancient North Siberians were largely replaced by populations carrying ancestry closely related to East Asians. This was not a simple migration but a prolonged process of demographic turnover, admixture, and regional extinction.

Out of this transformation emerged two closely related populations:

-

Ancestral Native Americans

-

Ancient Paleosiberians (AP)

Paleoclimatic modeling strongly supports southeastern Beringia as a long-term refugium during the LGM, providing a stable ecological zone where these populations could persist, interact, and differentiate.

Climate and Environmental Shifts

-

Bølling–Allerød (c. 14,700–12,900 BCE): warming and moisture increase expanded boreal forest into valleys; salmon runs intensified; nearshore productivity rose.

-

Younger Dryas (c. 12,900–11,700 BCE): brief return to cooler, drier conditions; tundra patches expanded but ice-free coasts still offered reliable marine resources.

-

Early Holocene (after c. 11,700 BCE): stabilizing warmth and rising sea level reshaped shorelines; taiga expanded fully; rich riverine and estuarine habitats matured.

Subsistence and Settlement

-

Deglaciating coasts supported seal and salmon economies; intertidal shellfish beds and seabird rookeries fueled seasonal aggregation.

-

In warming phases, diets diversified toward fish (salmon, sturgeon), small game, and plant foods (nuts, roots, berries).

-

Younger Dryas prompted higher mobility and renewed emphasis on large herbivores where herds persisted.

-

Early Holocene villages favored river confluences and coastal terraces, ideal for salmon weirs and broad foraging radii.

Technology and Material Culture

-

Microblade production refined; hafted composite points standardized for hunting and sealing.

-

Bone/antler harpoons with toggling tips; barbed fishhooks; sewing kits for tailored garments and waterproof seams.

-

Early pottery appears in the Lower Amur–Russian Far East and spreads to surrounding basins—among the world’s earliest ceramic traditions—used for fish oils, stews, and nut processing.

-

Ground-stone adzes for wood-working and dugout canoe manufacture; slate knives on some Okhotsk coasts.

Movement and Interaction Corridors

-

Amur–Sungari waterway integrated interior and coast; Sakhalin–Kuril–Hokkaidō island chain enabled short-hop voyaging.

-

Beringian standstill: populations on both sides of the strait developed long-term ties; fluctuating sea levels modulated contact.

-

Seasonal sea-ice bridges facilitated winter travel; summer lanes favored canoe movement.

Cultural and Symbolic Expressions

-

Carved bone and ivory figurines, zoomorphic engravings, and ochre burials persisted, signaling continuity with earlier Upper Paleolithic symbolic systems.

-

Recurrent salmon first-catch rites and bear/sea-mammal treatment practices are inferred from patterned discard and ritualized processing locales.

Environmental Adaptation and Resilience

-

Zonal mobility (taiga–tundra–coast) and storage (dried fish, rendered oils) buffered climate swings across Bølling–Allerød → Younger Dryas → Early Holocene.

-

Canoe technologies, fish weirs, and shoreline mapping (capes, tide rips, haul-outs) underwrote stable subsistence as forests spread and shorelines shifted.

Genetic and Linguistic Legacy

-

Prolonged Beringian population structure during late glacial–early Holocene times contributed ancestry to Paleo-Inuit and to the First Americans; reciprocal gene flow linked Chukchi–Kamchatka–Amur families.

-

These deep ties foreshadowed later circum-North Pacific cultural continuities in salmon ritual, dog-traction, and composite toolkits.

Transition Toward the Holocene Forager Horizons

By 7,822 BCE, Northeast Asia featured mature taiga coasts, prolific salmon rivers, and early pottery villages—a landscape primed for the broad-spectrum, semi-sedentary foraging economies that would dominate the Early Holocene and eventually feed into Epi-Jōmon/Satsumon, Okhotsk, and Amur basin cultural florescences.

Groups

Topics

- Paleolithic

- Last glacial period

- The Upper Paleolithic

- Last Glacial Maximum (LGM)

- Oldest Dryas

- Quaternary extinction event

- Bølling Oscillation

- Older Dryas

- Allerød Oscillation

- Late Glacial Maximum

- Younger Dryas