Northeastern Eurasia (28,577 – 7,822 BCE): Late …

Years: 28577BCE - 7822BCE

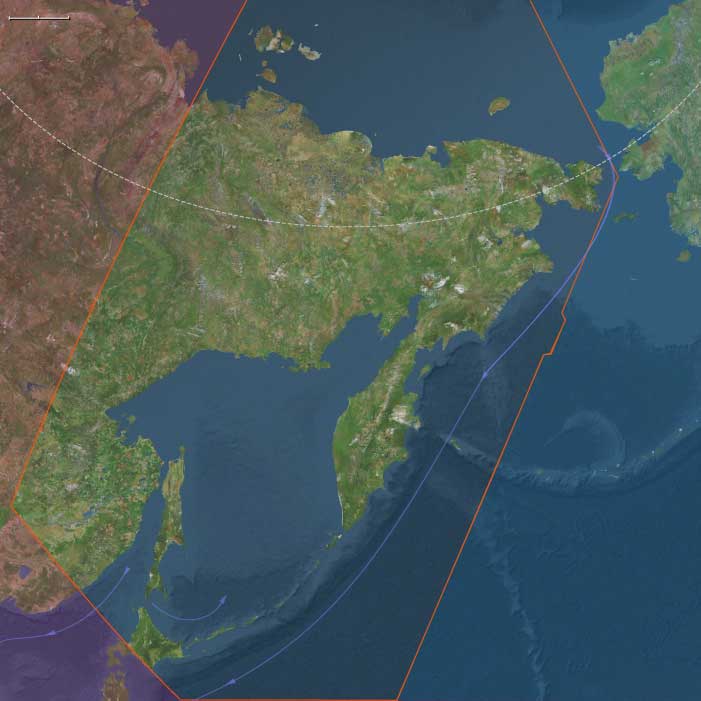

Northeastern Eurasia (28,577 – 7,822 BCE): Late Pleistocene–Early Holocene — Beringian Migrations, Salmon Economies, and the First Pottery Traditions

Geographic & Environmental Context

At the end of the Ice Age, Northeastern Eurasia—stretching from the Urals to the Pacific Rim—was a vast, deglaciating world of river corridors, boreal forests, and emerging coasts. It included three key cultural–ecological spheres:

-

Northwest Asia — the Ob–Irtysh–Yenisei heartlands, Altai piedmont lakes, and Minusinsk Basin, bounded by the Ural Mountains to the west. Here, deglaciation produced pluvial lake systems, and forest belts climbed into the Altai foothills.

-

East Europe — from the Dnieper–Don steppe–forest margins to the Upper Volga–Oka and Pripet wetlands, a corridor of interlinked rivers and pluvial basins supporting rich postglacial foraging.

-

Northeast Asia — the Amur and Ussuri basins, the Sea of Okhotsk littoral, Sakhalin and the Kuril–Hokkaidō arc, Kamchatka, and the Chukchi Peninsula—a maritime–riverine realm where early Holocene foragers developed salmon economies and pottery traditions under the warming Pacific westerlies.

Together these subregions formed a continuous arc of adaptation spanning tundra, taiga, and coast—an evolutionary laboratory for the technologies and traditions that would later circle the entire North Pacific.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

-

Bølling–Allerød (14,700–12,900 BCE): Rapid warming and higher precipitation expanded boreal forests and intensified riverine productivity across Eurasia’s north. Salmon runs strengthened in the Amur and Okhotsk drainages; pluvial lakes filled the Altai basins.

-

Younger Dryas (12,900–11,700 BCE): A temporary cold–dry reversal restored steppe and tundra, constraining forests to valleys; lake levels fell; inland mobility increased.

-

Early Holocene (after 11,700 BCE): Stable warmth and sustained moisture drove forest advance (pine, larch, birch) and high lake stands; sea levels rose along the Okhotsk and Bering coasts, flooding older plains and establishing modern shorelines.

These oscillations forged adaptable forager systems able to pivot between large-game mobility and aquatic specialization.

Subsistence & Settlement

Across the northern tier, lifeways diversified and semi-sedentism began to take root:

-

Northwest Asia:

Elk, reindeer, beaver, and fish formed broad-spectrum diets. Lakeside camps in the Altai and Minusinsk basins became seasonal home bases, while Ob–Yenisei channels hosted canoe or raft mobility. Forest nuts and berries expanded plant food options in warm phases. -

East Europe:

Along the Dnieper, Don, and Upper Volga, foragers targeted elk, red deer, horse, and beaver, exploiting riverine fish and waterfowl. Repeated occupations at lake outlets and confluences reflect increasing site permanence and food storage. -

Northeast Asia:

The Amur–Okhotsk region pioneered salmon-based economies, anchoring early Holocene villages at river confluences and estuarine terraces. Coasts provided seal, shellfish, seabirds, and seaweeds, while inland foragers pursued elk and musk deer. Winter sea-ice hunting alternated with summer canoe travel along the Sakhalin–Kuril–Hokkaidō chain.

This mosaic of economies—lake fishers, river hunters, and sealers—reflected the continent’s growing ecological diversity.

Technology & Material Culture

Innovation was continuous and regionally distinctive:

-

Microblade technology persisted across all subregions, with refined hafting systems for composite projectiles.

-

Bone and antler harpoons, toggling points, and gorges evolved for intensive fishing and sealing.

-

Ground-stone adzes and chisels appeared, enabling woodworking and boat construction.

-

Early pottery, first along the Lower Amur and Ussuri basins (c. 15,000–13,000 BCE), spread across the Russian Far East—among the world’s earliest ceramic traditions—used for boiling fish, storing oils, and processing nuts.

-

Slate knives and grindstones at Okhotsk and Amur sites show specialized craft economies.

-

Personal ornaments in amber, shell, and ivory continued, while sewing kits with eyed needles and sinew thread supported tailored, waterproof clothing.

These toolkits established the technological template for later northern and Pacific Rim foragers.

Movement & Interaction Corridors

-

Ob–Irtysh–Yenisei river systems funneled movement north–south, linking the steppe with the taiga and tundra.

-

Altai and Ural passes maintained east–west contact with Central Asia and Europe.

-

Dnieper–Volga–Oka networks merged the European forest-steppe into the greater Eurasian exchange field.

-

In the Far East, the Amur–Sungari–Zeya–Okhotsk corridor unified interior and coast, while the Sakhalin–Kuril–Hokkaidō arc allowed short-hop voyaging.

-

Across the Bering Strait, fluctuating sea levels intermittently connected Chukotka and Alaska, maintaining Beringian gene flow and cultural exchange.

These conduits supported both biological and technological diffusion at a continental scale.

Cultural & Symbolic Expressions

-

Ochre burials with ornamented clothing and ivory or antler goods reflect deep symbolic continuity from the Upper Paleolithic.

-

Petroglyphs and engravings in the Altai and Minusinsk basins, and later in Kamchatka, depict large animals, waterbirds, and solar motifs.

-

Amur basin figurines and carved marine-mammal and fish effigies attest to ritualized relationships with food species.

-

In the Far East, early evidence of first-salmon and bear-rite traditions foreshadows later Ainu and Okhotsk ceremonialism.

Across all subregions, water and game remained the core of spirituality, connecting people to cyclical abundance and ancestral landscapes.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

Foragers across Northeastern Eurasia met environmental volatility with creative versatility:

-

Zonal mobility (taiga–tundra–coast) and multi-season storage (dried meat, smoked fish, rendered oils) stabilized food supply.

-

Boat and ice technologies extended reach across seasons.

-

Broad-spectrum diets cushioned against climatic downturns.

-

Flexible dwellings and social alliances allowed fission and fusion as resources shifted.

-

Memory landscapes—engraved rocks, ritual mounds, named rivers—preserved continuity through spatial change.

Genetic and Linguistic Legacy

The Beringian population standstill during the Late Glacial created a deep ancestral pool for both Paleo-Inuit and First American lineages, while reciprocal migration reconnected Chukchi, Kamchatkan, and Amur populations after sea-level rise.

These long-lived networks seeded circum-Pacific cultural parallels in salmon ritual, dog-traction, maritime hunting, and composite toolkits, forming the northern backbone of later trans-Pacific cultural continuity.

Long-Term Significance

By 7,822 BCE, Northeastern Eurasia had become one of the world’s great centers of forager innovation:

-

Northwest Asia’s pluvial lakes fostered early semi-sedentism and the first rock art of Siberia.

-

East Europe’s river–lake foragers stabilized broad-spectrum economies bridging steppe and forest.

-

Northeast Asia’s salmon-rich coasts and early pottery traditions created the technological and ritual matrix that would radiate across the North Pacific.

This continental synthesis of aquatic resource mastery, ceramic innovation, and long-range mobility defined the emerging Holocene north—a zone where people and landscape adapted together through water, ice, and memory.

Groups

Topics

- Paleolithic

- Last glacial period

- The Upper Paleolithic

- Last Glacial Maximum (LGM)

- Oldest Dryas

- Quaternary extinction event

- Bølling Oscillation

- Older Dryas

- Allerød Oscillation

- Late Glacial Maximum

- Younger Dryas