Northeastern Eurasia (2637 – 910 BCE): Bronze …

Years: 2637BCE - 910BCE

Northeastern Eurasia (2637 – 910 BCE): Bronze and Early Iron — Steppe, Forest, and Sea Corridors of the North

Regional Overview

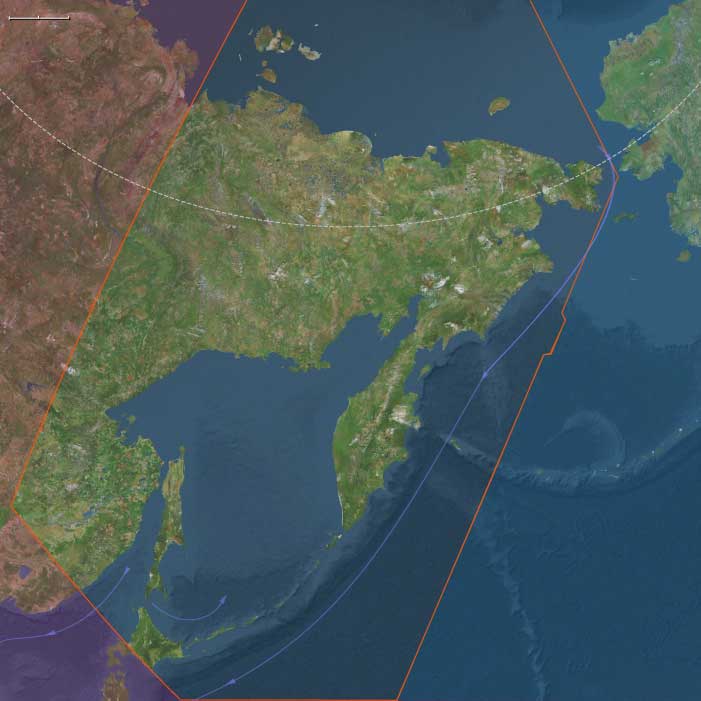

Stretching from the Carpathian steppes to the Amur River and Okhotsk coast, Northeastern Eurasia formed one of the great connective tissues of the ancient world.

It was a realm where bronze, horses, and furs flowed between the Eurasian heartlands and the Pacific Rim.

Across its vastness, riverine farming villages, pastoral nomads, and maritime foragers forged adaptive systems that endured millennia of climatic and cultural change.

Geography and Environment

Northeastern Eurasia comprised three immense cultural landscapes:

-

the steppe–forest–river corridor of East Europe,

-

the mountain–basin–taiga arc of Northwest Asia, and

-

the riverine–maritime frontier of Northeast Asia.

From the Black and Caspian seas to the Pacific, the region spanned temperate forests, arid grasslands, and subarctic coasts.

Major waterways—the Dniester, Volga, Ob, Yenisei, and Amur—served as continental highways, uniting inland producers with distant trade spheres.

Climate and Environmental Shifts

After 2600 BCE, gradual cooling tempered the mid-Holocene warmth.

Aridity cycles reshaped steppe ecology, encouraging mobility, while northern forests and salmon rivers remained stable.

Periodic droughts on the southern plains were balanced by resource-rich rivers and coasts farther north, allowing the region to function as an interconnected ecological mosaic.

Societies and Political Developments

East Europe – Forest–Steppe Gateways

Here, mixed farmers and herders shared the landscape with mobile steppe nomads.

The Catacomb and later Srubnaya cultures built kurgan mounds and timbered graves, developing chariotry and equestrian prestige.

Northern forest peoples pursued hunting, trapping, and fishing while trading furs and amber downriver.

The great river valleys—Dnieper, Don, and Volga—became arteries of a transcontinental economy linking the Baltic, Black Sea, and Caspian worlds.

Northwest Asia – Steppe Nomads and Metallurgists

The Andronovo and Karasuk cultures of the Altai–Yenisei region perfected pastoral nomadism and bronze metallurgy.

Horse herding, dairy use, and wheeled vehicles expanded mobility across Western Siberia’s open plains.

Petroglyphs of riders, chariots, and solar emblems testify to a cosmology centered on the sun, sky, and movement.

Taiga foragers and herders exchanged furs and fish for metals, linking steppe caravans with Arctic rivers.

Northeast Asia – River Chiefs and Maritime Foragers

Along the Amur–Ussuri system and Okhotsk coast, salmon-based chiefdoms controlled fisheries and trade in furs, oils, and metals.

Small quantities of bronze and iron filtered in via Manchuria and Korea, while local economies remained rooted in fishing, hunting, and limited horticulture.

On Hokkaidō, Epi-Jōmon cultures maintained complex foraging traditions, blending marine resources with emerging agricultural knowledge.

By the end of the period, lineages of riverine leaders managed alliances and ceremonial feasts, precursors to the Okhotsk and Satsumon societies.

Economy and Technology

-

Agriculture and Herding: Mixed grain cultivation and livestock herding characterized steppe and forest-steppe zones; pastoral nomads relied on horses, cattle, and sheep, while northern groups emphasized fish, game, and reindeer.

-

Metallurgy: Bronze dominated the toolkit—axes, daggers, ornaments; iron appeared only near the close of the epoch.

-

Mobility: Wagons, chariots, skin boats, and sledges made this one of the most mobile regions of the ancient world.

-

Trade: Amber, furs, wool, horses, and metals crossed from Europe to Asia; tin and jade moved westward; long rivers bound inland communities to coastal trade.

Cultural and Symbolic Expressions

Across Northeastern Eurasia, ritual landscapes reflected a shared reverence for ancestors, animals, and the sun.

-

Steppe kurgans enshrined warriors and chieftains beneath earthen mounds.

-

Taiga and Amur villages offered fish, weapons, and carved idols in riverbanks and wetlands.

-

Rock art portrayed hunters, charioteers, solar disks, and ships, blending ecological observation with spiritual cosmology.

-

Feasting and gift exchange affirmed alliances across the vast ecological frontier.

Environmental Adaptation and Resilience

Mobility was the key to survival.

Nomads tracked pastures; fishermen followed salmon runs; foragers shifted with game migrations.

Diversified economies—grain, herds, fish, and furs—buffered communities against drought or freeze.

Storage pits, smoked fish, and dried meat ensured winter security, while interregional exchange redistributed surpluses.

Regional Synthesis and Long-Term Significance

By 910 BCE, Northeastern Eurasia was a continent-spanning web of pastoral, agrarian, and maritime societies.

Its steppe corridors funneled innovations—horse riding, chariots, metallurgy—between Europe and East Asia.

Its riverine and coastal frontiers sustained rich fisheries and trade nodes that would feed into later Silk Road systems.

The fusion of mobility, metallurgy, and environmental adaptability forged one of humanity’s most enduring cultural ecologies—a dynamic northern realm bridging the forests of Europe, the deserts of Central Asia, and the seas of the Pacific Rim.

Groups

- Jomon culture

- Chukchi

- Koryaks

- Ulch people

- Japan, Middle Jomon Period

- Japan, Late Jomon Period

- Japan, Final Jomon Period