Northeast Asia (1828–1971 CE): Tsarist Frontiers, Imperial …

Years: 1828 - 1971

Northeast Asia (1828–1971 CE): Tsarist Frontiers, Imperial Japan, and Cold War Divisions

Geography & Environmental Context

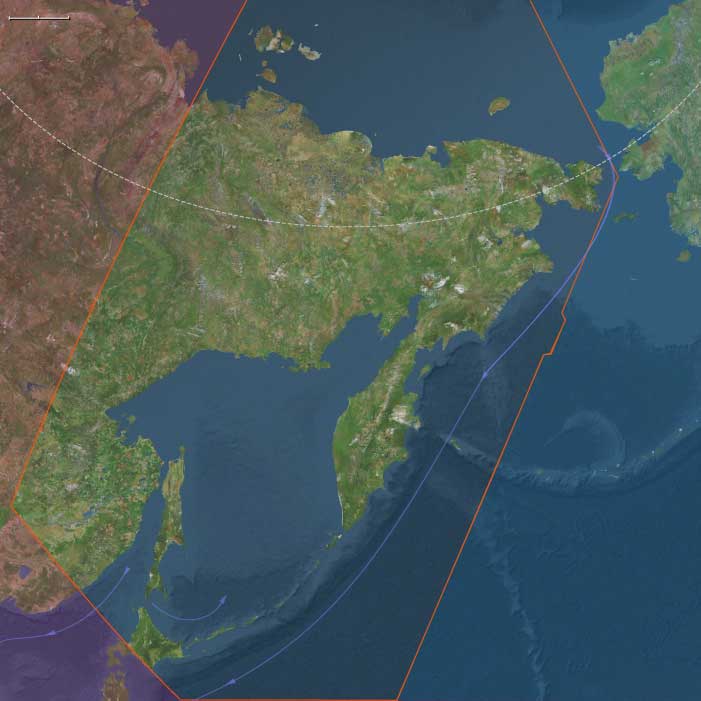

Northeast Asia includes eastern Siberia (east of 130°E, including Primorsky Krai and Sakhalin), northeastern Heilongjiang in China, the Chukchi Peninsula, Wrangel Island, and Hokkaidō (except its extreme southwest). Anchors include the Amur and Ussuri river basins, the Sea of Okhotsk, the Kamchatka Peninsula, and the Kuril Islands. The region combines Arctic tundra, boreal taiga, volcanic arcs, and rich marine coasts.

Climate & Environmental Shifts

A sharply continental climate defined the region: long winters, permafrost, and short summers. Droughts and harsh freezes (dzud) devastated herds in Siberian and Amur zones. Volcanic eruptions on Kamchatka and earthquakes in Sakhalin and Hokkaidō periodically destroyed settlements. Sea ice patterns shaped fishing and navigation. After 1945, industrialization and nuclear testing added new ecological pressures.

Subsistence & Settlement

-

Indigenous lifeways: Chukchi, Even, Koryak, and Nivkh peoples herded reindeer, hunted seals and whales, fished rivers, and gathered wild plants.

-

Russian settlement: From the mid-19th century, Tsarist Russia expanded along the Amur and into Primorsky Krai, founding Vladivostok (1860). Sakhalin became a penal colony.

-

Japanese settlement: Hokkaidō was colonized intensively after 1869, displacing Ainu through farming, fishing, and mining.

-

20th century: Soviet collectivization transformed Siberian villages; reindeer herding was reorganized into state farms. Postwar, Vladivostok, Khabarovsk, and Magadan became industrial hubs; Norilsk and Kolyma further west relied on forced labor.

Technology & Material Culture

-

Transport: River steamers plied the Amur; the Trans-Siberian Railway (1891–1916) tied Vladivostok to Moscow. Japan built railroads and ports in Hokkaidō. Postwar, Soviet highways, airfields, and gulag transport routes extended deep into the taiga.

-

Industry: Fishing, fur trade, timber, coal (Sakhalin), and later oil and military industries dominated. Hokkaidō developed mining, steel, and agriculture.

-

Everyday life: Yurts and wooden huts persisted in Siberia, while Soviet apartments (khrushchyovki) and Japanese wooden houses spread in urbanizing zones. Radios, sewing machines, and later TVs entered households after 1945.

Movement & Interaction Corridors

-

Tsarist conquest: Treaties of Aigun (1858) and Peking (1860) gave Russia the Amur–Ussuri territories.

-

Japanese expansion: Hokkaidō fully colonized; Sakhalin and the Kurils contested in Russo-Japanese War (1904–05).

-

Labor & exile: Penal labor on Sakhalin; Soviet deportations and gulags (Kolyma) forced millions east.

-

Military corridors: WWII saw Japanese control of southern Sakhalin and Kurils; Soviets seized them in 1945. Cold War militarization followed.

Cultural & Symbolic Expressions

-

Indigenous traditions: Shamanic ceremonies, reindeer festivals, and whale rituals persisted under suppression.

-

Colonial suppression: Ainu were displaced and assimilated in Japan; Nivkh and Chukchi were collectivized in USSR.

-

Literature: Accounts of exile (Chekhov on Sakhalin, 1890), gulag memoirs, and Japanese colonial writings depicted the region as harsh frontier.

-

Identity: Soviet patriotism celebrated Far Eastern development; Japan romanticized Hokkaidō as a northern frontier.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

-

Nomadic strategies: Reindeer herding diversified herds across tundra and taiga.

-

Fishing adaptation: Salmon runs sustained both Indigenous and settler economies; Soviet trawlers industrialized fisheries.

-

Cold adaptation: Fur clothing, log cabins, and later insulated housing ensured survival.

-

Modern pressures: Mining, deforestation, and gulag projects scarred landscapes but also supported settlement.

Political & Military Shocks

-

Russian empire: Secured Amur and Primorye in mid-19th century; Sakhalin developed as penal colony.

-

Russo-Japanese War (1904–05): Japan seized southern Sakhalin and challenged Russian Pacific presence.

-

World War II: Soviet offensives in 1945 seized Kurils and southern Sakhalin; Indigenous and Japanese civilians displaced.

-

Cold War: Vladivostok became closed Soviet naval base; Kurils remained disputed. Hokkaidō developed rapidly within U.S.-allied Japan, hosting defense installations.

-

Repression: Soviet collectivization, gulag labor, and forced sedentarization of nomads; Japanese assimilation of Ainu.

Transition

From 1828 to 1971, Northeast Asia transformed from Indigenous homelands and penal colonies into a militarized frontier of empires and Cold War blocs. Tsarist Russia absorbed Amur and Primorye, while Japan colonized Hokkaidō and contested Sakhalin and Kurils. WWII and Soviet offensives redrew borders, displacing populations. Collectivization, gulags, and industrialization under the USSR, and modernization in Hokkaidō under Japan, altered lifeways profoundly. By 1971, Northeast Asia was a land of naval bases, mines, fisheries, and Cold War garrisons, where Indigenous cultures persisted in fragments beneath the weight of empire and modern state power.

People

Groups

- Koryaks

- Chukchi

- Nivkh people

- Evens, or Eveny

- Yukaghirs

- Ainu people

- Buddhism

- Siberian Yupiks

- Itelmens

- Evenks

- Kereks

- Alyutors

- Chinese Empire, Qing (Manchu) Dynasty

- Russian Empire

- Japan, Empire of (Meiji Period)

- Japan, Taisho Period

- Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR), or Soviet Union

- Japan, Showa Period

Topics

- Russian Colonization of Siberia

- Maritime Fur Trade

- Russo-Japanese War

- Russian Revolution of 1905

- World War, Second (World War II)

- Second World War in the Pacific

- Cold War