Northeastern Eurasia (1540–1683 CE) Muscovy’s Ascent, …

Years: 1540 - 1683

Northeastern Eurasia (1540–1683 CE)

Muscovy’s Ascent, Siberia’s Expansion, and the Persistence of the Northern Peoples

Geography & Environmental Context

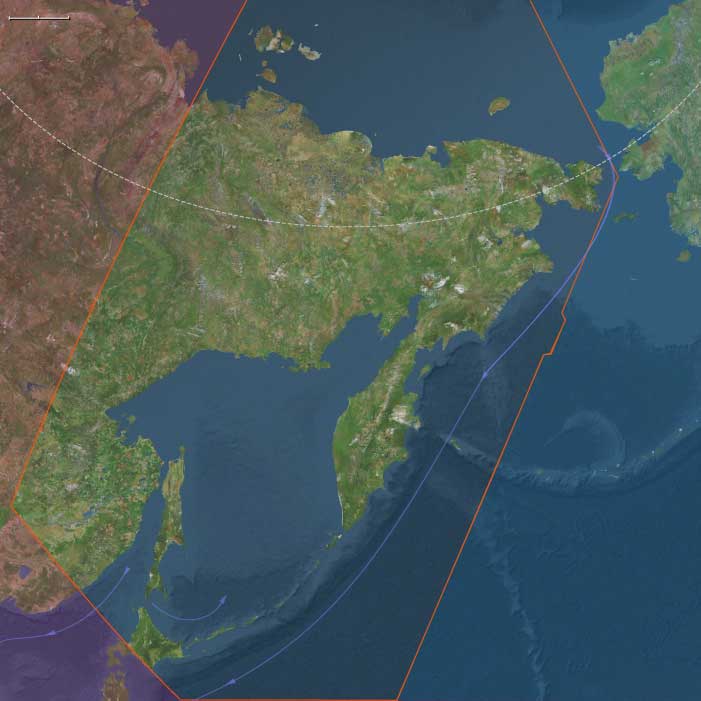

From the Urals to the Pacific, and from the Baltic–Volga corridor to the Bering Strait, Northeastern Eurasia formed a single evolving sphere of contact and conquest.

-

East Europe: The forested and riverine plains of Muscovy, framed by the Volga, Oka, and Dnieper, blended into the steppe marches of the Don and the forest frontier of the Urals.

-

Northwest & Northeast Asia: Beyond the Urals stretched the taiga and tundra basins of the Ob, Yenisei, and Lena, widening into the salmon-rich Amur and Okhotsk seas, and the volcanic and forested arc of Hokkaidō, Sakhalin, and the Chukchi Peninsula.

The Little Ice Age deepened winters and shortened growing seasons. Harsh frosts, heavy snowpacks, and spring floods alternated with droughts on the steppe, forcing agrarian, pastoral, and hunting societies alike to synchronize with a demanding climate.

Political & Military Transformations

The Muscovite Heartland and the Rise of the Russian State

In the 16th century, Ivan IV (the Terrible) unified the Russian principalities under a centralized autocracy, establishing the Tsardom of Muscovy. His conquest of Kazan (1552) and Astrakhan (1556) extended control down the Volga, integrating Turkic, Finno-Ugric, and Bashkir populations and opening trade to the Caspian and Central Asia.

Muscovy’s territorial reach grew dramatically:

-

West: conflict with Poland-Lithuania and Sweden in the Livonian War (1558–1583) brought costly defeats but framed enduring western ambitions.

-

South: fortified lines against Crimean Tatars anchored the steppe frontier.

-

East: Cossack expeditions over the Urals began the conquest of Siberia.

After Ivan’s death, civil war and famine produced the Time of Troubles (1600–1613), ended only by the election of Mikhail Romanov. The early Romanovs rebuilt administration, regularized taxation, and turned expansion eastward again. By the 1670s Muscovy had stabilized from the Baltic to the Urals and projected tributary control far into Asia.

The Conquest of Siberia and the Building of an Inland Empire

The overthrow of Khan Kuchum’s Siberian Khanate (1580s–1598) opened the western taiga to Russian forts (ostrogs) and fur tribute (yasak). A chain of riverine strongholds—Tyumen (1586), Tobolsk (1587), Tomsk (1604), Yeniseisk (1619), Krasnoyarsk (1628)—extended imperial authority to the Yenisei, then the Lena.

Cossack detachments levied furs from Khanty, Mansi, Selkup, Evenk, and other peoples, while epidemics and forced labor decimated many communities. Resistance flared repeatedly but was contained through punitive raids and hostage diplomacy. By mid-century Tobolsk had become the administrative and ecclesiastical capital of Siberia.

Frontier Societies and Indigenous Worlds

Across the taiga and tundra, indigenous economies persisted through mobility and diversification:

-

Forest hunters and fishers (Khanty, Mansi, Evenk, Selkup, Nenets) followed migratory cycles of sable, elk, and sturgeon.

-

Steppe-forest margins hosted Bashkir and Tatar pastoralists, oscillating between trade and rebellion.

-

Amur and Okhotsk lowlands were home to Daur, Nanai, Nivkh, and Udege farmers and fishers, while on Hokkaidō the Ainu combined salmon fisheries, acorn gathering, and trade with Japanese brokers.

Cultural life revolved around shamanism, clan feasts, and reciprocity with animal spirits. Russian Orthodoxy reached the taiga through priests accompanying forts; icons stood beside shaman drums in early hybrid spaces of belief.

Movement & Exchange Corridors

-

Volga–Oka–Don complex: Linked Moscow to the Caspian, Persia, and Central Asia; carried grain, timber, and iron eastward, and silk and horses westward.

-

River highways of Siberia: Ob, Irtysh, Yenisei, and Lena functioned as year-round trade and tribute routes—boats in summer, sleds on winter ice.

-

Arctic & Steppe routes: The Mangazeya sea road briefly connected the Kara coast to Europe; southern caravans from Bukhara brought iron and cloth.

-

Amur–Okhotsk–Hokkaidō circuits: Nivkh and Ainu navigators maintained coastal and island exchanges, while late-17th-century Russian scouts and Matsumae merchants began to appear at their margins.

-

Administrative chains: Couriers connected new towns east of the Urals to Moscow, binding frontier outposts into the tsar’s bureaucracy.

Economy & Material Culture

Fur was the universal currency—“soft gold.” Sable, fox, and ermine financed expansion and diplomacy. Indigenous crafts—birch-bark canoeing, snowshoeing, skin-boat building—remained essential. Russian technology introduced firearms, iron axes, ovens, and log construction. In agriculture, limited rye and hemp fields near forts supplied garrisons. Along the Amur and in Hokkaidō, iron kettles and silk cloth entered indigenous prestige economies.

Cultural & Intellectual Life in East Europe

Within Muscovy itself, architecture, icon painting, and chronicles flourished under both Ivan IV and the early Romanovs. The St. Basil’s Cathedral (1561) on Red Square symbolized sacral kingship. Printing presses, schools, and monastery scriptoria multiplied. The Orthodox Church, elevated to patriarchal status in 1589, unified doctrine and education.

The 17th century saw intense religious debate culminating in Patriarch Nikon’s reforms (1650s) and the Old Believer schism, a rift that scattered dissenters eastward into Siberia—ironically spreading literacy and crafts along the frontier. Cossack culture, meanwhile, produced oral epics and icon-bordered folklore celebrating free service and frontier piety.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

Agrarian core regions stabilized through new plow techniques, monastery granaries, and famine relief systems. In Siberia, cache storage, mixed subsistence, and mobility buffered scarcity. Fur cycles were managed through rotational hunting; floodplain hay meadows sustained livestock. The indigenous emphasis on multi-resource economies proved the key to endurance under both climatic and colonial pressure.

Conflict and Diplomacy

-

Wars in the West: Muscovy fought prolonged struggles with Poland-Lithuania and Sweden for Baltic access; though often checked, these campaigns forged a permanent standing army.

-

Southern Frontier: Raids from the Crimean Tatars persisted; the Don Cossacks both defended and disrupted imperial order.

-

Eastern Contact: By the 1670s Russian explorers on the Amur were clashing with Qing patrols, preluding the Treaty of Nerchinsk (1689).

-

Internal Revolts: Tax burdens and service demands provoked peasant risings, notably the Razin rebellion (1670–1671), echoing wider tensions between frontier autonomy and central control.

Transition & Legacy (to 1683 CE)

By 1683, Northeastern Eurasia had transformed from a mosaic of forest tribes, steppe khanates, and trading chiefdoms into an interlinked system dominated by the expanding Russian state.

-

In East Europe, the Romanovs consolidated a multiethnic empire, fusing Orthodox identity with autocracy.

-

Across Siberia, the fort chains, yasak tribute, and missionary outposts formed the backbone of a continental empire.

-

In Northeast Asia, indigenous polities still commanded their rivers and fisheries, though encircled by Russian, Qing, and Japanese influence.

From the Volga to the Amur, the age forged the infrastructure, ideology, and frontier experience that would sustain Russian imperial power for centuries—an empire born from ice roads, fur caravans, and the tenacity of peoples who made their living where the forests met the frozen sea.

Groups

- Nivkh people

- Evens, or Eveny

- Buddhism

- Ainu people

- Jurchens

- Evenks

- Russia, Tsardom of

- Later Jin (Manchu Khanate)

- Manchus

Topics

Commodoties

- Fish and game

- Hides and feathers

- Gem materials

- Glass

- Domestic animals

- Grains and produce

- Strategic metals