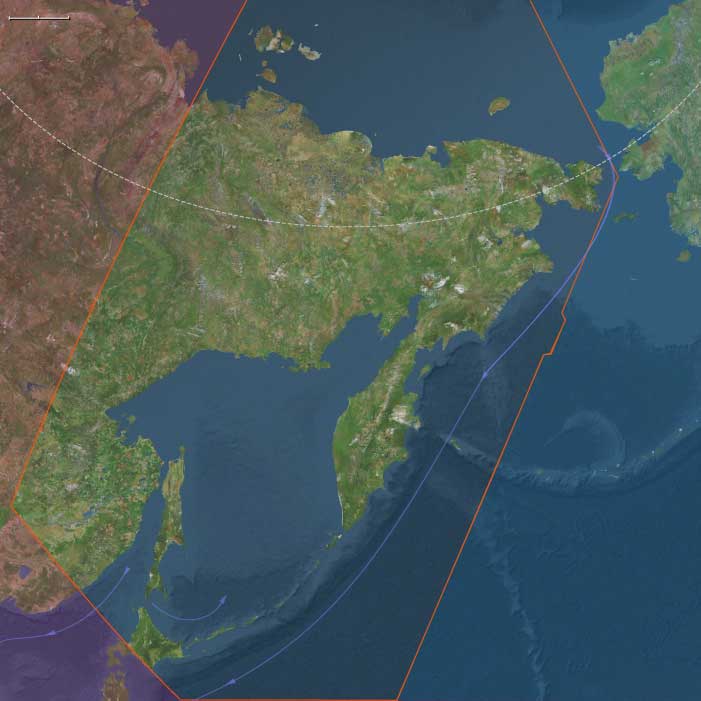

Northeastern Eurasia (1252–1395 CE): Forest Frontiers, Steppe …

Years: 1252 - 1395

Northeastern Eurasia (1252–1395 CE): Forest Frontiers, Steppe Realignments, and Northern Exchange

From the fur forests of the Volga–Oka basin to the salmon rivers of Sakhalin and Kamchatka, Northeastern Eurasia in the Lower Late Medieval Age formed the great ecological hinge between Europe and the Pacific. Across twelve time zones of tundra, taiga, and steppe, Mongol suzerainty, frontier trade, and native lifeways interwove into a vast and fluid world bound by furs, fish, and faith.

The Mongol World and the Forest Frontier

In the thirteenth century, the Mongol conquests reshaped the political geography of the northern continent. The Golden Horde, ruling from its Volga capital at Sarai, dominated the steppes between the Urals and the Dnieper. Tribute, census, and courier systems extended northward into the Rus’ forests, transforming older principalities into tributary states. Farther east, the Ilkhanid, Chagatai, and Yuan branches of the empire controlled Central Asia, Iran, and China, enclosing the great Eurasian fur belt within a single imperial framework.

Beneath this canopy of conquest, indigenous societies persisted. The Khanty, Mansi, and Selkup peoples of the Ob–Irtysh–Yenisei valleys, and the Evenki hunters of the taiga, maintained clan economies of fishing, trapping, and seasonal herding. Furs—sable, marten, squirrel, and ermine—moved down frozen rivers to the tribute markets of the Golden Horde, exchanged for salt, iron, and cloth. In the Altai and Sayan mountains, Turkic–Mongol pastoralists grazed herds of horses, sheep, and camels, while the Yenisei Kyrgyz and rising Oirat confederations negotiated power between forest and steppe.

East Europe under Mongol Suzerainty

To the west, the principalities of Rus’ adapted to life under Horde rule. The Mongol campaigns of 1237–1240 shattered the Kievan commonwealth, yet cities such as Vladimir, Suzdal’, and Tver’ survived by paying tribute. The new power center of Moscow, under Ivan I Kalita and Dmitry Donskoy, rose as the Horde’s favored tax collector. The victory at Kulikovo Field (1380) became a lasting symbol of resistance, though the city was soon sacked by Toqtamish (1382).

Meanwhile, the Novgorod Republic, shielded by forests and swamps, retained autonomy under Horde suzerainty. Governed by its veche assembly, it thrived on the fur trade, sending pelts, wax, and honey through Hanseatic kontorsat Visby and Toruń. To the southwest, Lithuania expanded under Gediminas and Algirdas, seizing Kiev (1362) and extending rule over most of Belarus and Ukraine. The Union of Krewo (1385) linked Lithuania and Poland in a dynastic and religious alliance, bringing the western forest-steppe into Latin Christendom.

The Siberian and Amur Realms

Beyond the Urals, Mongol authority thinned but trade intensified. The Ob, Irtysh, and Yenisei corridors became the highways of the fur economy, their frozen surfaces serving as winter roads. The Golden Horde levied tribute through steppe brokers, while taiga hunters retained mobility and autonomy. By the fourteenth century, the Oirats of the Altai had begun to eclipse older tribes, and Islam spread among the southern steppe Tatars even as shamanic traditions persisted in the forests.

Farther east, along the Amur, the Yuan dynasty extended its reach to the Pacific. Expeditions of the 1270s–1330s subdued Nivkh and Nanai clans on Sakhalin, exacting furs and falcons for the imperial tribute rolls. The empire’s northernmost subjects sent offerings of sable and eagle feathers to Beijing in exchange for silk, iron, and prestige goods. In northern Hokkaidō, Ainu communities consolidated during this same period, trading dried fish and furs to Wajin (Japanese) merchants from Honshū. Ritual leaders and traders emerged as chiefs of semi-hereditary domains, their culture crystallized in the bear-sending rite (iyomante) that honored the spirits of animal patrons.

In the Kamchatka Peninsula, the Koryak herders and Itelmen fishers combined coastal sea-mammal hunting with inland reindeer mobility, while the Chukchi linked the Bering shore to the Siberian interior. Across the Bering Strait, contacts with Yupik and Inuit communities remained episodic but steady, transferring tools, hides, and myths between Eurasia and America.

Economies of Fur, Fish, and Exchange

Everywhere across the northern latitudes, the fur trade functioned as currency. Furs moved west to the Volga, south to the Yuan and Ming courts, and east into Japanese and Korean markets. Iron and cloth, scarce in the north, circulated back through Baltic merchants, Mongol caravans, and Wajin traders. In the forest-steppe and taiga, winter ice served as the season of transport: sled convoys and dog teams carried tribute along frozen rivers, while summer canoes threaded through lakes and portages.

In the Baltic and Arctic margins, fishing and seal hunting matched the fur trade in importance. Dried salmon, cod, and seal oil provisioned both villages and ships. Novgorodian merchants tapped the fisheries of the White Sea, while Ainu and Amur fishermen adapted weirs, wicker traps, and bone harpoons to each river system. In the taiga, beekeeping and reindeer herding supplemented hunting, creating mixed economies that could absorb climatic shocks.

Belief, Ritual, and Cultural Synthesis

Despite Mongol conquest and tributary hierarchies, Northeastern Eurasia retained a remarkable religious pluralism.

-

In the Rus’ lands, Orthodox Christianity spread northward through monasteries founded by Sergius of Radonezh, while the Horde’s ruling elite adopted Islam yet tolerated Christian and Jewish communities.

-

In the Amur and Hokkaidō zones, animist cosmologies thrived: Ainu and Nivkh shamans honored salmon, bears, and sea spirits through elaborate rites of reciprocity.

-

Across the steppe and forest, Tengrist and Buddhist influences mingled with Islamic and Christian forms, producing a syncretic frontier spirituality.

Ritual, in every climate, served social cohesion. Feasts, first-fish rites, and shared tribute ceremonies governed resource use and mediated clan disputes, ensuring survival where centralized states could not.

Adaptation and Resilience

Ecological diversity underpinned endurance. Communities combined herding, hunting, fishing, and limited cultivation according to latitude and season. When steppe pastures failed, forest products and furs replaced lost income; when fishing runs declined, herders moved south or west. Tribute relations with distant empires—whether to Sarai, Dadu, or Moscow—were accepted as the price of stability and access to imported goods. Across regions, mobility, not stasis, defined resilience: from the sled trails of the Yenisei to the plank boats of the Amur, the peoples of the north adjusted to climate and empire alike.

Long-Term Significance

By 1395 CE, Northeastern Eurasia had coalesced into a vast but loosely integrated frontier.

-

The Golden Horde still dominated the western steppe, though fractured by internal wars and Timur’s invasions.

-

In the forests of Rus’, Moscow and Novgorod emerged as twin poles of power and commerce.

-

The Oirats consolidated in the Altai, while the Ming inherited Yuan tributary patterns along the Amur.

-

Ainu and Amur peoples sustained independent economies of salmon, fur, and ritual, their autonomy protected by distance and climate.

Across the entire north, the twin currencies of fur and fish and the languages of trade and tribute bound Europe and Asia together. The region’s enduring ecological wealth and mobility made it the silent backbone of late medieval Eurasia—supplying luxury markets, sustaining frontiers, and foreshadowing the great northern expansions of the centuries to come.

Groups

- Koryaks

- Chukchi

- Ulch people

- Nivkh people

- Ainu people

- Buddhism

- Mohe people

- Wajin

- Inuit

- Siberian Yupiks

- Itelmens

- Nanai people

- Northern Yuan dynasty

- Chinese Empire, Ming Dynasty

Commodoties

- Fish and game

- Weapons

- Hides and feathers

- Gem materials

- Glass

- Domestic animals

- Oils, gums, resins, and waxes

- Grains and produce

- Textiles

- Strategic metals

- Manufactured goods