Northeastern Eurasia (1108 – 1251 CE): Forest …

Years: 1108 - 1251

Northeastern Eurasia (1108 – 1251 CE): Forest Empires and Steppe Frontiers

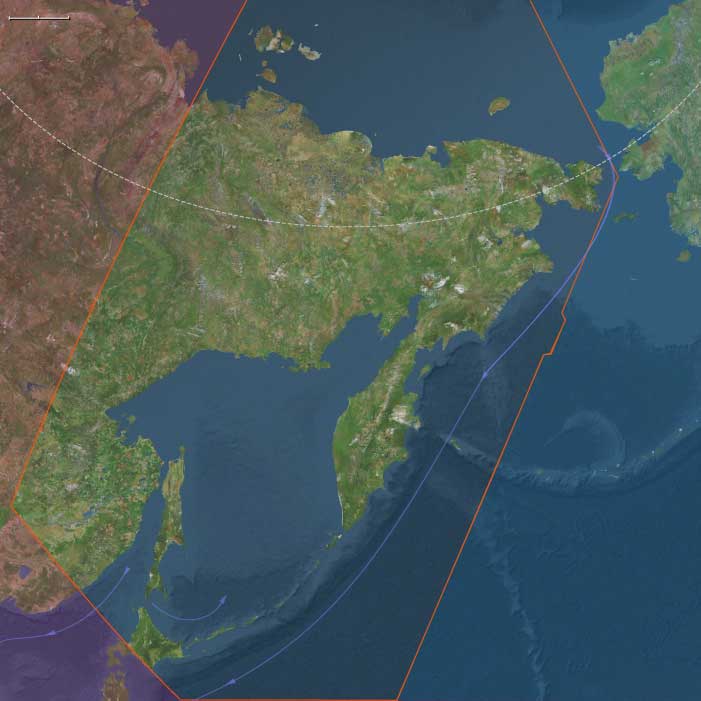

Between 1108 and 1251 CE, Northeastern Eurasia was transformed from a mosaic of forest kingdoms and steppe confederations into the frontier of the Mongol world.

From the Amur River and Hokkaido to the Volga and Urals, new powers rose amid ecological wealth and continental expansion.

The Jurchen forged an empire in the east; Turkic and Kipchak nomads ruled the western steppe; and the fragmented Rus’ principalities contended with both Christian and shamanic frontiers before succumbing to Mongol conquest.

This was an age of mobility, resilience, and convergence—when rivers, forests, and grasslands became conduits of empire.

Geographic and Environmental Context

Northeastern Eurasia stretched from the Pacific coasts of the Sea of Okhotsk and the Bering Sea across the Amur basin, Siberian taiga, and steppe corridors to the Volga–Don–Dnieper plains of Eastern Europe.

It encompassed four great ecological zones:

-

The Amur basin and Manchurian forests of the Jurchen and Tungusic peoples;

-

The Siberian taiga and river networks of Ob, Yenisei, and Lena;

-

The Kipchak and Cuman steppe, bridging the Urals and Black Sea;

-

The Slavic forest-steppe, from Novgorod to Kiev and Vladimir-Suzdal.

These regions were bound together by rivers—the Amur, Volga, Ob, and Dnieper—forming a transcontinental lattice of trade and migration.

Climate and Environmental Shifts

During the Medieval Warm Period, milder temperatures lengthened growing seasons in the Amur basin and forest-steppe, supporting millet and rye cultivation.

Steppe pastures flourished, expanding herding economies and nomadic confederations.

The taiga and tundra, though cold, yielded rich furs, fish, and reindeer pastures.

This climatic stability fueled demographic growth and cross-ecological exchange—from Amur agriculture to Volga fur trade—creating the material base for imperial expansion.

Societies and Political Developments

The Jurchen and the Jin Empire (1115–1234):

The Jurchens, a Tungusic people from the Amur basin, overthrew the Khitan Liao and founded the Jin dynasty in northern China.

They blended sedentary agriculture, hunting, and cavalry warfare, ruling from Zhongdu (Beijing) while maintaining their Manchurian heartland.

Their military power rested on armored cavalry and composite bows; their culture fused shamanism with Chinese statecraft.

By 1234, the Mongols had destroyed the Jin, incorporating Manchuria into their empire.

The Steppe and the Kipchak Confederation:

To the west, Turkic Kipchaks (Polovtsy) dominated the steppe from the Irtysh to the Dnieper, controlling caravan routes and serving as mercenaries and horse traders.

They linked the Siberian forests to the Black Sea markets, mediating between Islamic Central Asia and Christian Rus’.

Their confederation began to fracture under Mongol advance after 1220, leading to the rise of the Golden Horde in the mid-13th century.

The Forest Peoples of Siberia:

Ob-Ugric and Samoyedic societies—the Khanty, Mansi, Nenets, and Selkup—maintained hunting, fishing, and reindeer herding across the taiga.

Clan structures and animist rituals governed resource use, while furs and slaves were exchanged southward for metal and salt.

These groups remained autonomous until Mongol and Russian expansion centuries later.

The Fragmented Rus’ Principalities:

After the decline of Kievan Rus’, regional powers emerged:

-

Novgorod, governed by merchant boyars, thrived on Baltic trade.

-

Vladimir-Suzdal rose in the northeast, laying the foundation for Muscovy.

-

Galicia-Volhynia controlled the western frontier near Poland and Hungary.

Southern Rus’ faced constant pressure from the Cumans, while Orthodox monasteries preserved literacy and faith.

From 1223 (Battle of the Kalka River) to 1240 (Sack of Kiev), Mongol armies under Batu Khan subjugated Rus’, establishing tribute rule through the Golden Horde.

The Mongolic Advance:

By the early 13th century, Temüjin (Chinggis Khan) unified Mongol tribes, then absorbed Turkic and Tungusic neighbors.

His campaigns swept westward across Siberia and into Eastern Europe, forging a continental network of conquest, trade, and communication that transformed the region’s political geography forever.

Economy and Trade

Northeastern Eurasia’s wealth lay in ecological diversity:

-

Amur Basin: millet, soybeans, hemp, and fish fed the Jurchen core.

-

Steppe: horses, sheep, and camels supported nomadic confederations.

-

Forest and tundra: furs, wax, and reindeer products entered long-distance trade.

-

Rus’ cities: exported wax, honey, furs, and slaves via the Volga and Dnieper to Byzantium and the Baltic.

Major trade arteries:

-

Amur–Ussuri river routes linking Manchuria to the Pacific.

-

Ob–Yenisei–Irtysh network joining Siberian hunters to steppe nomads.

-

Volga–Caspian corridor channeling Rus’ and Kipchak trade into the Islamic world.

-

Dnieper–Black Sea route connecting Kiev to Byzantium.

By the mid-13th century, the Mongols had integrated these disparate circuits into one imperial economy stretching from China to the Danube.

Subsistence and Technology

-

Jurchen agriculture used slash-and-burn and permanent fields; their cavalry revolutionized warfare in Manchuria.

-

Steppe nomads perfected mounted archery, using yurts and herds as mobile assets.

-

Forest peoples employed birchbark canoes, skis, and sleds for seasonal hunting and transport.

-

Rus’ settlements used watermills and iron tools; kremlins (fortified towns) arose along trade routes.

-

Ainu, Chukchi, and Koryak combined maritime hunting and reindeer herding with spiritual reciprocity toward nature.

Together these technologies of mobility and adaptation allowed human settlement across one of the world’s most extreme environments.

Belief and Symbolism

Faith and cosmology mirrored ecology and power:

-

Shamanism united forest and steppe peoples through reverence for sky, animal, and ancestral spirits.

-

Tengriism sanctified the nomadic order of the Mongols and Kipchaks.

-

Orthodox Christianity unified the Rus’ under Byzantine cultural influence.

-

Buddhist and Daoist ideas filtered northward through the Jin and Tangut realms.

-

Among the Ainu, Chukchi, and Koryak, rituals of reciprocity with animal spirits preserved environmental equilibrium.

Religion became the principal vector of cultural exchange—from Orthodox missions in Karelia to Buddhist texts carried by caravans.

Movement and Interaction Corridors

-

The Amur River system: artery of agriculture, trade, and Jurchen expansion.

-

The Ob and Yenisei rivers: linked fur frontiers to Central Asia and Volga markets.

-

The Steppe Road: nomadic highway connecting Mongolia, Kipchak plains, and Eastern Europe.

-

The Dnieper and Volga routes: carried merchants, warriors, and monks between Rus’ and Byzantium.

-

The Arctic seaways and Bering Strait: sustained cultural continuity between Chukchi and Alaskan Inuit.

These corridors transformed the Eurasian north from isolated ecologies into a dynamic continental web.

Adaptation and Resilience

-

Ecological flexibility—farming, herding, hunting—ensured survival in diverse climates.

-

Political pluralism—city republics, nomadic clans, tribute networks—absorbed shocks from invasion and climate.

-

Cultural continuity—shamanism and Orthodoxy alike—provided spiritual stability amid conquest.

-

Mongol integration replaced fragmentation with imperial networks that protected trade and communication.

Resilience in this frontier lay in diversity: a patchwork of cultures thriving within the rhythms of steppe and forest.

Long-Term Significance

By 1251 CE, Northeastern Eurasia had been transformed:

-

The Jurchen Jin dynasty had risen and fallen to the Mongols, integrating Manchuria into a trans-Eurasian order.

-

The Kipchak steppe became the nucleus of the Golden Horde.

-

The Rus’ principalities endured under Mongol tribute, their centers shifting north toward Moscow.

-

The forest and tundra peoples maintained autonomy at the edges of empire.

-

Across the Pacific, the Ainu, Chukchi, and Koryak preserved ancient lifeways amid new trade links.

In this age, conquest and ecology intertwined: the Mongols unified the steppe, the forests fed global commerce, and the great rivers carried Northeastern Eurasia into the heart of the medieval world-system.

Groups

- Koryaks

- Nivkh people

- Ainu people

- Buddhism

- Taoism

- Mohe people

- Okhotsk culture

- Satsumon culture

- Jurchens

- Liao Dynasty, or Khitan Empire

- Jin Dynasty (Chin Empire), Jurchen

- Jin Dynasty (Chin Empire), Jurchen

- Jin Dynasty (Chin Empire), Jurchen

Topics

Commodoties

- Fish and game

- Hides and feathers

- Gem materials

- Glass

- Domestic animals

- Grains and produce

- Strategic metals

- Salt

- Sweeteners

- Spices