Polynesia (964 – 1107 CE): Voyaging Renewals …

Years: 964 - 1107

Polynesia (964 – 1107 CE): Voyaging Renewals and Island States

Geographic and Environmental Context

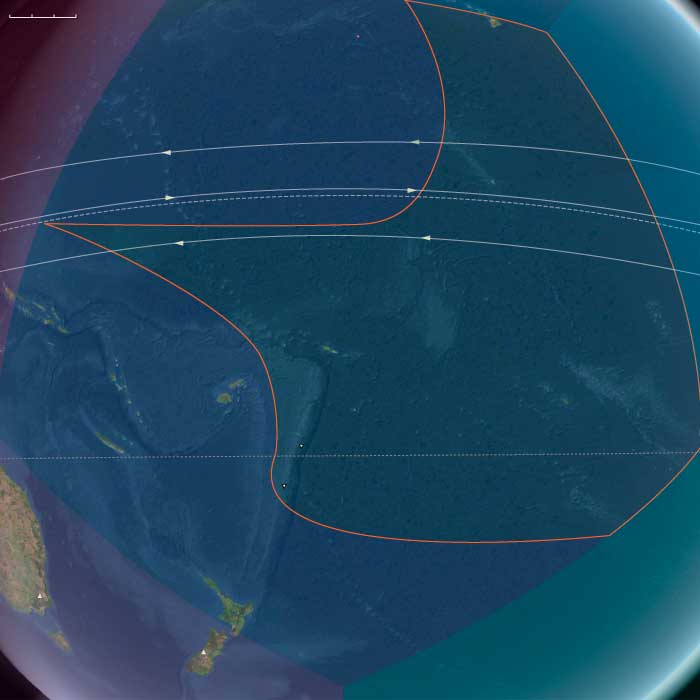

Polynesia, spanning the vast Pacific triangle from Hawaiʻi to Tonga and Rapa Nui, entered a period of dynamic cultural and environmental maturity during the Lower High Medieval Age.

The region’s three principal spheres—North Polynesia, West Polynesia, and East Polynesia—were linked by voyaging routes that fostered sustained contact, ritual exchange, and technological renewal.

High volcanic islands such as Oʻahu, Tonga, and Ra‘iātea supported intensive irrigation and monumental construction, while low coral atolls like Tokelau and Tuvalu relied on arboriculture and reef fisheries.

At the eastern fringe, new island groups—Rapa Nui and the Pitcairn–Henderson cluster—entered the Polynesian network through pioneering settlement voyages.

Climate and Environmental Shifts

The Medieval Warm Period (c. 950–1250 CE) brought stable, slightly warmer temperatures across the tropical Pacific.

Rainfall patterns favored high-island agriculture but remained uneven on atolls, where prolonged droughts required redistribution of food and water via inter-island exchange.

Reliable wind patterns and calmer seas extended navigable seasons, reinforcing the cultural renaissance of long-distance voyaging and ritual integration.

Societies and Political Developments

Across the Polynesian world, social hierarchies consolidated around chiefly lineages, priestly authority, and ritual centers.

-

In North Polynesia, aliʻi nui coordinated ridge-to-reef resource systems that evolved into proto-ahupuaʻa, uniting agricultural valleys, upland forests, and reef fisheries under coherent management.

-

In West Polynesia, the Tuʻi Tonga dynasty established the first transoceanic polity, extending influence through Samoa, Fiji, and the Cook Islands, while Taputapuātea marae on Ra‘iātea became a sacred pan-Polynesian nexus.

-

Samoan councils maintained equilibrium through federated chiefdoms and oratory, contrasting with Tongan centralization yet remaining pivotal to regional diplomacy.

-

In East Polynesia, the colonization of Rapa Nui marked the outermost expansion of Polynesian civilization, while the Pitcairn–Henderson–Mangareva triangle sustained a specialized exchange economy.

Economy and Trade

Intensified agriculture underpinned demographic growth:

-

Irrigation systems expanded, particularly the loʻi kalo terraces of Hawaiʻi and the yam and taro pondfields of Tonga and Samoa.

-

Fishponds (loko iʻa) reached new scale and sophistication, converting nearshore lagoons into managed aquaculture zones.

-

High-island surpluses—dried fish, breadfruit paste, and preserved meats—were exchanged with atoll communities for mats, shells, and canoe timber.

-

Prestige goods—fine mats (ʻie tōga), basalt adzes, barkcloth, and feather regalia—circulated widely through ritual tribute and marriage alliances.

These networks sustained both subsistence and symbolic economies, binding distant archipelagos into a shared maritime system.

Belief and Symbolism

Polynesian cosmologies reached new coherence through institutionalized ritual centers:

-

Heiau and marae served as nodes linking divine ancestry, agricultural fertility, and chiefly legitimacy.

-

The Taputapuātea cult articulated a theology of shared descent and sacred voyaging, enshrining Ra‘iātea as the “navel of the world.”

-

Tongan divine kingship manifested in monumental langi tombs, while Samoan ritual oratory and fine-mat exchanges sanctified social harmony.

-

On Rapa Nui, early ahu platforms signified ancestral veneration and the first expressions of a monumental stone tradition that would later define the island.

Adaptation and Resilience

Polynesian societies combined technological ingenuity with ecological foresight:

-

Distributed production across terraced valleys, coastal fishponds, and reef zones buffered against drought and storm.

-

Communal labor cycles maintained irrigation and aquaculture systems, ensuring continuity of food security.

-

Inter-island reciprocity provided redundancy; famine or cyclone losses on one island could be offset through ceremonial redistribution.

-

Ritual calendars coordinated agricultural and fishing seasons, while the kapu system protected spawning grounds and sacred forests.

Long-Term Significance

By 1107 CE, Polynesia exhibited one of the most integrated oceanic civilizations on Earth:

-

North Polynesia developed complex, ecologically integrated ahupuaʻa systems.

-

West Polynesia achieved both political and ritual unity through the Tuʻi Tonga dynasty and the Taputapuātea cult.

-

East Polynesia witnessed the final wave of human settlement, extending the Polynesian world to its easternmost frontier.

These developments laid the institutional, technological, and cosmological foundations for the grand Polynesian expansions and state formations of the subsequent centuries.