West Polynesia (909 BCE – 819 CE): …

Years: 909BCE - 819

West Polynesia (909 BCE – 819 CE): Post-Lapita Transformations — Tonga–Samoa Chiefdom Seeds, Outlier Visits Elsewhere

Geographic & Environmental Context

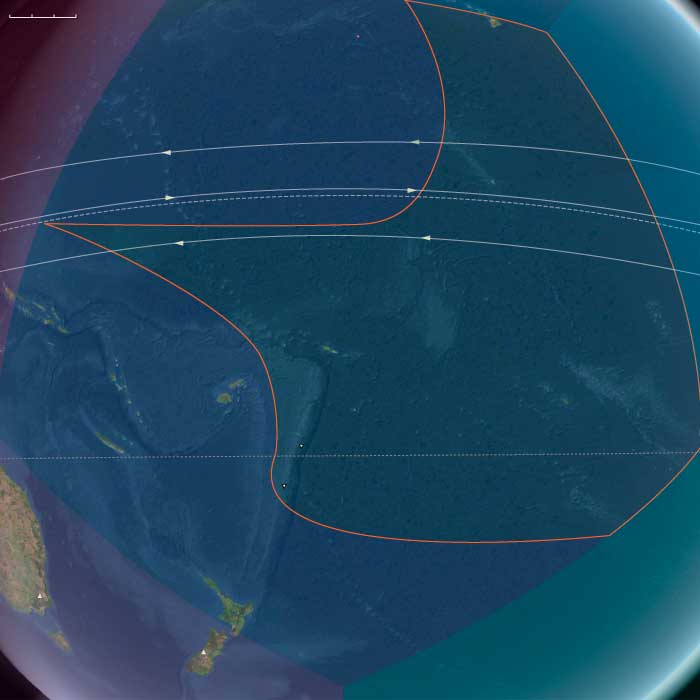

West Polynesia includes Hawaiʻi Island (the Big Island); Tonga (Tongatapu, Haʻapai, Vavaʻu); Samoa (Savaiʻi, Upolu, Tutuila/Manuʻa); Tuvalu and Tokelau (low atolls); the Cook Islands (Rarotonga, Aitutaki, Mangaia, etc.); Society Islands (Raiatea–Tahiti–Moʻorea–Bora Bora); and the Marquesas (Nuku Hiva, Hiva Oa)

-

Anchors (settled cores): Tongatapu–Haʻapai–Vavaʻu, Savaiʻi–Upolu.

-

Unsettled or only transiently visited: Hawaiʻi Island, Society Islands, Marquesas, much of the Cook Islands, Tuvalu–Tokelau (some atolls may see late first-millennium CE initial landfalls beyond this cutoff).

Climate & Environmental Shifts

-

First-millennium oscillations moderate; cultivation and arboriculture consolidate on leeward plains; reef fisheries stable.

Subsistence & Settlement

-

Post-Lapita societies in Tonga–Samoa: villages aggregate; irrigated taro and dryland field systems expand; breadfruit/coconut groves mature.

-

Fish weirs and nearshore net fisheries standardized; pig/chicken husbandry routine.

Technology & Material Culture

-

Local ceramic traditions simplify as tapa and woodwork ascend; shell/stone adzes refined; canoe sail/rig innovations tuned to prevailing trades.

-

Ornamental whale tooth, pearlshell, and feather regalia appear.

Movement & Interaction Corridors

-

Robust Fiji–Tonga–Samoa exchange; long-haul probes to Cooks–Societies–Marquesas likely increase late in this epoch (but enduring settlements there generally post-date 819 CE); Hawaiʻi Island remains uncolonized.

Cultural & Symbolic Expressions

-

Emergent sacred precincts (marae/ahu) formalize chiefly ritual; lineage genealogies anchor land–sea tenure.

-

Foundational navigation lore (star paths, swell reading, seabird cues) transmitted in guilds—precondition for the later settlement wave across Cooks–Societies–Marquesas–Hawaiʻi.

Environmental Adaptation & Resilience

-

Agroforestry mosaics (breadfruit–canoe timber–taro ponds) and storm-siting strategies buffer cyclones and drought; marine closures support reef resilience.

Transition

By 819 CE, Tonga–Samoa sustain thriving post-Lapita chiefdom seeds; the wider West Polynesian sphere (including Societies, Marquesas, Cooks, Hawaiʻi Island) remains largely unsettled within this epoch—but navigational capacity and cultural templates are in place for the first-millennium CE → early second-millennium colonization pulse documented in our later-age entries.

Groups

Commodoties

Subjects

Regions

Subregions

Related Events

Filter results

Showing 10 events out of 47 total

Near East (909 BCE – 819 CE) Early Iron and Antiquity — Greeks of Ionia, Levantine Tyre, Roman–Byzantine Egypt, Arabia’s Caravans

Geographic and Environmental Context

The Near East includes Egypt, Sudan, Israel, most of Jordan, western Saudi Arabia, western Yemen, southwestern Cyprus, and western Turkey (Aeolis, Ionia, Doris, Lydia, Caria, Lycia, Troas) plus Tyre (extreme SW Lebanon).-

Anchors: the Nile Valley and Delta; Sinai–Negev–Arabah; the southern Levant (with Tyre as the sole Levantine node in this subregion); Hejaz–Asir–Tihāma on the Red Sea; Yemen’s western uplands/coast; southwestern Cyprus; western Anatolian littoral (Smyrna–Ephesus–Miletus–Halicarnassus–Xanthos; Troad).

Climate & Environment

-

Nile’s late antique variability; Aegean storms seasonal; Arabian aridity persistent but terraces/cisterns mitigated.

Societies & Political Developments

-

Western Anatolia Greek city-states (Ionia–Aeolia–Doria, with Troad): Miletus, Ephesus, Smyrna, etc.

-

Tyre (sole Near-Eastern Levantine node here) dominated Phoenician seafaring.

-

Egypt (Ptolemaic → Roman → Byzantine): Nile granary and Christianizing hub.

-

Arabian west: caravan kingdoms and Hejaz–Asir oases; western Yemen incense terraces and caravan polities.

-

Southwestern Cyprus embedded in Hellenistic–Roman maritime circuits.

Economy & Trade

-

Grain–papyrus–linen from the Nile; olive–wine Aegean; incense–myrrh from Yemen; Red Sea lanes linked to Aden–Berenike nodes (outside core but connected).

-

Tyre exported craft goods and purple dye.

Technology & Material Culture

-

Iron agriculture and tools; triremes and merchant galleys; advanced terracing, cisterns; lighthouse/harbor works.

Belief & Symbolism

-

Egyptian polytheism → Christianity (Alexandria); Greek civic cults; Tyrian traditions; Arabian deities; monasticism along Nile/Desert.

Adaptation & Resilience

-

Canal maintenance buffered Nile shocks; terraces/cisterns stabilized Arabian farming; Aegean coastal redundancy protected shipping routes.

Transition

By 819 CE, the Near East was a multi-corridor world of Nile granaries, Ionia’s city-coasts, Tyre’s Phoenician legacy, and Arabian incense roads — a foundation for the medieval dynamics ahead (Ayyubids in Syria/Egypt next door, Abbasids beyond, and the Ionian–Anatolian littoral under Byzantine/Nicaean arcs).

Middle East (909 BCE – 819 CE) Early Iron and Antiquity — Urartu, Achaemenids, Parthians, Sasanian Frontiers

Geographic and Environmental Context

The Middle East includes Iraq, Iran, Syria, Armenia, Georgia, Azerbaijan, eastern Jordan, most of Turkey’s central/eastern uplands (including Cilicia), eastern Saudi Arabia, northern Oman, Qatar, Bahrain, the UAE, northeastern Cyprus, and all but the southernmost Lebanon.-

Anchors: the Tigris–Euphrates alluvium and marshes; the Zagros (Luristan, Fars), Alborz, Caucasus (Armenia–Georgia–Azerbaijan); northern Syrian plains and Cilicia; Khuzestan and Fars lowlands; the Arabian/Persian Gulf littoral (al-Ahsa–Qatar–Bahrain–UAE–northern Oman); northeastern Cyprus and the Lebanon coastal elbow (north).

Climate & Environment

-

Continental variability; oases survived by canal upkeep; Gulf fisheries stable; Caucasus snows fed headwaters.

Societies & Political Developments

-

Urartu (9th–6th c. BCE) fortified Armenian highlands;

-

Achaemenid Persia (6th–4th c. BCE) organized satrapies across Iran, Armenia, Syria uplands, Cilicia; Royal Road linked Susa–Sardis through our zone.

-

Hellenistic Seleucids, then Parthians (3rd c. BCE–3rd c. CE) and Sasanians (3rd–7th c. CE) ruled Iran–Mesopotamia; oases prospered under qanat/karez and canal regimes.

-

Transcaucasus (Armenia, Iberia/Georgia, Albania/Azerbaijan) oscillated between Iranian and Roman/Byzantine influence; northeastern Cyprus joined Hellenistic–Roman networks.

-

Arabian Gulf littoral hosted pearling/fishing and entrepôts (al-Ahsa–Qatif–Bahrain).

Economy & Trade

-

Irrigated cereals, dates, cotton, wine; transhumant pastoralism; Gulf pearls and dates.

-

Long-haul Silk Road and Royal Road flows; qanat irrigation expanded in Iran.

Technology & Material Culture

-

Iron plowshares, tools, and weapons; fortifications; qanat engineering; road stations (caravanserais earlier variants).

-

Arts: Urartian bronzes; Achaemenid stonework; Sasanian silver; Armenian and Georgian ecclesiastical arts (late).

Belief & Symbolism

-

Zoroastrianism, Armenian/Georgian Christianity, local cults; Jewish and early Christian communities in oases/ports; syncretism in frontier cities.

Adaptation & Resilience

-

Canal/qanat redundancy, pasture–oasis integration, distributed entrepôts (northeastern Cyprus, Gulf) hedged war and drought.

Transition

By 819 CE, the Middle East was a layered highland–oasis–Gulf system under Sasanian–Byzantine frontiers giving way to Islamic polities.

The Middle East: 909–766 BCE

Assyrian Imperial Surge and Expansion

Beginning with Adad-nirari II (911–891 BCE), the Neo-Assyrian Empire rapidly expands, firmly establishing itself as a dominant regional power. By 904 BCE, Babylonia is subdued and reduced to vassalage, and strategic control is secured along the Khabur River. Adad-nirari's military successes lay a robust foundation for Assyria's extensive territorial ambitions.

Consolidation and Brutality under Ashurnasirpal II

Ashurnasirpal II (883–859 BCE) aggressively expands Assyria westward, reaching the Mediterranean by 859 BCE and incorporating influential Phoenician cities. Ashurnasirpal II's administration is marked by brutal reprisals against rebels, including mass executions and mutilations, instilling fear to suppress dissent. His lavish new capital at Kalhu (Nimrud), featuring monumental palaces and relief sculptures, symbolically projects Assyrian power and authority.

Continued Expansion and Conflict under Shalmaneser III

Shalmaneser III (859–824 BCE) extends Assyria's dominance further, notably conquering the powerful Aramaean state of Bit-Adini and engaging a regional coalition led by Damascus. Despite temporary resistance, Shalmaneser III successfully enforces tribute from Phoenician cities, Israel, and Damascus. His reign also witnesses increasing military confrontations with the emerging northern kingdom of Urartu, a significant competitor based near Lake Van.

Internal Turmoil and Territorial Instability

Internal strife emerges toward the end of Shalmaneser III’s rule, culminating in a civil war (828–826 BCE) against his rebellious son, Ashurdaninpal. This turmoil weakens central authority, leading to territorial losses. His successor, Shamsi-Adad V (824–811 BCE), gradually stabilizes the empire, incorporating the strategically vital region of Chaldea. Under Adad-nirari III (811–783 BCE), aided initially by Queen Sammuramat (legendary Semiramis), Assyria reasserts dominance, notably reclaiming Damascus by 804 BCE.

Cultural and Linguistic Influences of the Aramaeans and Phoenicians

The Aramaeans, influential traders settled in Greater Syria, significantly shape regional commerce and culture. They simplify the Phoenician alphabet, spreading Aramaic as the dominant lingua franca across the Middle East, even becoming the official language of the later Persian Empire. Meanwhile, the Phoenicians, despite Assyrian dominance, maintain extensive trade networks and cultural resilience. Artifacts such as the sarcophagus of King Ahiram from Byblos illustrate a vibrant exchange of Assyrian, Egyptian, and Phoenician artistic styles.

Anatolian and Iranian Regional Powers

In Anatolia, the Phrygians, heirs to Hittite cultural traditions, revitalize regional prosperity from their capital at Gordium. They excel in metalworking, woodcarving, and textiles, significantly influencing regional trade and cultural exchange. Concurrently, the Mannaean state emerges around 850 BCE in northwestern Iran, characterized by fortified cities, advanced irrigation, and horse breeding, representing an important regional power.

Emergence and Rivalries of Urartu

In the north, the kingdom of Urartu solidifies under King Aramu (circa 860–843 BCE), becoming a persistent and formidable rival to Assyria. Urartu's strategic fortifications and sustained resistance mark significant geopolitical shifts, frequently clashing with Assyrian ambitions.

Innovations in Assyrian Military and Artistic Expression

Assyrian military advancements, particularly in cavalry tactics, significantly enhance their imperial capabilities. Artistic and architectural achievements, notably the iconic man-headed winged bulls and elaborate palace reliefs, symbolize imperial power and divine sanction, emphasizing the Neo-Assyrian Empire’s cultural sophistication.

Cyprus: Political Consolidation and Urbanization

Cyprus experiences considerable urban growth and political consolidation during this period, with significant centers like the kingdom of Salamis flourishing through extensive trade networks. Monumental "Royal" tombs underscore the island’s rising wealth and social complexity.

Decline and Instability under Shalmaneser IV

Shalmaneser IV (782–772 BCE) faces severe setbacks, culminating in his defeat and death in 772 BCE, triggering internal chaos and territorial losses. This period of instability underscores the challenges Assyria faces in maintaining its extensive empire amidst ongoing regional conflicts.

Thus, the era from 909 to 766 BCE encapsulates a profound and transformative phase in Middle Eastern history, marked by dynamic imperial expansion, significant cultural exchanges, geopolitical rivalries, and internal political struggles that shape the region for centuries.

The Aramaeans had moved into in Greater Syria around the end of the thirteenth century BCE, approximately the same time at which ancestral Israelites migrated to the area.

Settling in the Mesopotamian-Syrian corridor to the north, the Aramaeans had established the kingdom of Aram, biblical Syria.

As overland merchants, they open trade to southwestern Asia, and their capital at Damascus becomes a city of immense wealth and influence.

The Aramaeans build a huge fortress at Aleppo, its foundations still intact.

They simplify the Phoenician alphabet and carry their language, Aramaic, to their chief areas of commerce.

Aramaic displaces Hebrew in Greater Syria as the vernacular (Jesus will speak Aramaic), and it will become the language of commerce throughout the Middle East and the official language of the Persian Empire.

Aramaic will continue to be spoken in the Syrian countryside for almost a thousand years, and in the 1980s will remain in daily use in a handful of villages near the Syrian-Lebanese border.

A dialect of Aramaic continues to be the language of worship in the Syrian Orthodox Church.

Urartu reemerges in Assyrian inscriptions in the ninth century BCE as a powerful northern rival.

The Assyrians’ chief adversaries, the Aramaeans, have now settled in Syria.

Under Shalmaneser III, Ashurbanipal’s son and successor, the Assyrians finally manage to conquer Bit-Adini (Beth-Eden), the most powerful Aramaean state on the upper Euphrates.

A short-lived coalition of Levantine and Syrian states, led by Damascus and including Israel, checks Assyria’s westward designs.

Near East (909–766 BCE): Consolidation, Conflict, and Cultural Flourishing

Nubian Expansion and Egyptian Shifts

During the late ninth and early eighth centuries BCE, Egypt experiences significant geopolitical transformations. Kashta, a Kushite king based in Napata, expands his influence northward into Upper Egypt, notably installing his daughter Amenirdis I as the prospective God's Wife of Amun in Thebes. This effectively legitimizes Nubian dominance, paving the way for his son Piye to consolidate Kushite power across Egypt around 747 BCE. Under Piye's rule, Egyptian cultural and religious traditions experience revitalization, with an increasing adoption of Nubian elements.

Israel, Judah, and Regional Rivalries

This period sees Israel and Judah embroiled in frequent conflicts, both internally and with neighboring states. Notably, the Mesha Stele, or Moabite Stone, crafted by King Mesha of Moab around 850 BCE, provides critical historical insights. This stele details Mesha’s rebellion against Israelite domination under the "House of Omri," referencing the Israelite god Yahweh and potentially the earliest extrabiblical mention of the "House of David." The kingdoms of Edom and Moab also rise prominently, intensifying regional dynamics, with Edom gaining significance through increased trade and mining activities.

Israel under Omri (c. 876–869 BCE) and his son Ahab (c. 869–850 BCE) emerges as a significant regional power, marked by extensive military campaigns, construction projects, and an influential Phoenician alliance forged through Ahab’s marriage to Jezebel, daughter of Ithbaal of Tyre and Sidon. The internal religious turmoil intensifies with the clash between Phoenician Baal worship and Hebrew monotheism, particularly under the prophets Elijah and Elisha.

Assyrian Dominance and Local Autonomy

The Assyrian Empire, under rulers such as Shalmaneser III and later Tiglath-Pileser III, exerts considerable influence over the Near East, frequently subduing and extracting tribute from kingdoms such as Israel and the city-states of Phoenicia. Despite periodic revolts by city-states like Tyre and regional leaders, Assyria largely maintains its dominance through military might and political coercion, reshaping the political landscape significantly.

Sabaean Ascendancy and Arabian Trade

To the south, the Sabaean Kingdom in southern Arabia (biblical Sheba), beginning around the tenth century BCE, becomes a vital trade nexus connecting Arabia, Syria, and Mesopotamia. Controlling major caravan routes and flourishing economically, the Sabaeans significantly influence commerce and cultural exchanges across the Near East.

Greek Expansion in Anatolia and Cyprus

The collapse of Mycenaean civilization and the subsequent Dorian invasion in mainland Greece prompt waves of Ionian and Dorian refugees to establish new settlements in Asia Minor. The Ionian coast flourishes culturally and commercially with prominent cities such as Phocaea, Ephesus, and Miletus. Concurrently, the Dorians establish influential cities like Halicarnassus and Knidos, integrating into regional power dynamics through leagues like the Dorian Hexapolis. Cyprus also emerges as a significant cultural and commercial hub, with a Phoenician colony established at Citium around 800 BCE, contributing to the island's complex demographic and cultural landscape.

Cultural and Linguistic Developments

The Hebrew alphabet, evolving from Phoenician script, is reflected in early texts like the Gezer Calendar (tenth century BCE), demonstrating early literacy and agricultural traditions among the Israelites. Concurrently, the Elohist (E) textual source emerges, emphasizing Israel's northern kingdom perspectives, portraying a less anthropomorphic deity, Elohim, and competing religious practices.

Legacy of the Age

This age marks a profound consolidation and conflict across the Near East, with regional powers negotiating their positions amidst shifting alliances and rivalries. The cultural and political developments—ranging from Nubian expansion in Egypt, Hebrew religious struggles, Assyrian dominance, Greek colonization in Anatolia, to burgeoning Arabian trade—lay essential foundations for the complex historical trajectories that continue to shape the region's future.

The Middle East, 909 to 898 BCE: Expansion of Assyrian Dominance

Rise and Consolidation under Adad-nirari II

The Middle East experiences a pivotal shift with the emergence and rapid consolidation of the Neo-Assyrian Empire, initiated by the reign of King Adad-nirari II in 911 BCE. Succeeding his father, Ashur-dan II, Adad-nirari II embarks on ambitious military campaigns, significantly extending Assyrian control over territories eastward and northward.

Military Campaigns and Regional Subjugation

Adad-nirari II secures crucial victories against neighboring rivals, notably subjugating prominent Aramaean settlements and city-states, including Kadmuh and Nisibin. These victories yield considerable treasure, bolstering the economic strength of Assyria and stabilizing the strategically significant Khabur River region. The empire strategically resettles populations from conquered areas, dispersing them to distant territories to reduce resistance and fortify Assyrian rule.

Linguistic and Cultural Developments

In this period, Aramaic is formally recognized alongside Akkadian as an official language, reflecting the diverse linguistic landscape and administrative needs of the expanding empire. This significant administrative reform facilitates effective governance across the vast and culturally varied Assyrian territories.

Subjugation of Babylonia

A major milestone during this era is Assyria's successful campaigns against its traditional southern rival, Babylonia. By 904 BCE, Babylonia is effectively reduced to vassal status, marking a decisive shift in regional power dynamics and affirming Assyrian supremacy.

Historical Documentation and Chronological Precision

Adad-nirari II’s ascension in 911 BCE is of particular historical importance because it represents one of the earliest precisely dateable events in ancient Middle Eastern history. Comprehensive eponym lists meticulously document Assyrian history from this period onward, providing a reliable chronological framework that greatly enhances scholarly understanding of regional events.

This foundational era of Assyrian power not only redefines the political and military landscapes of the Middle East but also establishes the empire as a lasting force that shapes regional history profoundly in subsequent centuries.

Asa, the fifth king of the House of David and the third of the Kingdom of Judah, reigns in Jerusalem from around 913 to 873 BCE, or 911 to 870 BCE according to I Kings and II Chronicles, which describe his reign in a favorable manner.

According to this Biblical account, Azariah son of Oded, a prophet, had exhorted Asa early on to reinforce strict national observance of Judaism, and Asa paid heed.

He has purged the land of pagan cults, all the sites of idolatrous worship being completely destroyed and the worshipers persecuted.

The Queen Mother, Maacah, had also been deposed for having been involved with idol worship.

There had also been a large-scale crackdown on prostitutes.

Finally, when the religious renewal is completed in Asa's fifteenth year, a great feast is held in Jerusalem with many sacrifices at the Temple.

At this time, many northerners, particularly from the tribes Ephraim and Manasseh, immigrate to the Kingdom of Judah because they see the success of Asa's policies.

By contrast, there is internal conflict in the Kingdom of Israel because of the fall of the dynasty of Jeroboam.

The Middle East, 897 to 886 BCE: Consolidation Under Tukulti-Ninurta II

Following the transformative reign of Adad-nirari II, the Neo-Assyrian Empire enters a brief yet significant period of consolidation under his successor, Tukulti-Ninurta II, who ascends to the Assyrian throne in 891 BCE. Inheriting an empire greatly expanded by his predecessor, Tukulti-Ninurta II focuses on solidifying Assyrian control and maintaining its established territories rather than undertaking extensive new conquests.

Strategic Military Actions and Regional Stability

Tukulti-Ninurta II undertakes carefully targeted military campaigns aimed at reinforcing Assyrian supremacy. His reign sees successful operations against the Syro-Hittite, Babylonian, and Aramean city-states and regions. These campaigns serve to reaffirm and stabilize Assyrian dominance over previously conquered territories, discouraging rebellion and fostering administrative cohesion across the empire.

Eastern Frontiers: Zagros Campaigns

Notably, Tukulti-Ninurta II directs his military attention eastward, toward the rugged terrain of the Zagros Mountains. These campaigns effectively subjugate newly arrived groups of Iranic peoples, potentially including the early Medes. By securing these eastern frontier regions, Tukulti-Ninurta II ensures a stable buffer zone, protecting the empire from incursions and establishing a solid foundation for future expansions in this direction.

Administrative Continuity

Building upon the linguistic and administrative reforms established earlier, Aramaic continues to serve alongside Akkadian as an official administrative language. This linguistic policy facilitates efficient governance over the empire's culturally diverse and geographically extensive territories.

Preparing for Further Expansion

Though Tukulti-Ninurta II's reign is brief, his strategic actions significantly bolster Assyrian stability and regional control, laying critical groundwork for subsequent imperial expansion. By the end of his rule, the Assyrian Empire stands securely positioned, its power firmly established in the Middle Eastern political landscape, ready for the ambitious campaigns of future rulers.